Building the First Steiger Tractor

A Tribute to the Power of a Torch and a Welder

This short excerpt is from the book, Red 4WD Tractors. This portion takes place in fall 1957, when Douglass Steiger and his father, John, and brother, Maurice, determined they needed a larger tractor to have their farm continue to be profitable. They were interested in purchasing a Wagner tractor, which they could purchase for $24,000. They also believed they could build a tractor for $10,000. (You can meet Douglass and see Steiger #1 at Big Iron 2017 in Fargo--details here)

The Steigers had built several other pieces of equipment for the farm, including two self-propelled swathers, a rock picker, and a 60-foot weed sprayer. The 24-year-old Douglass reasoned they could build their own four-wheel-drive tractor using used parts and a hand-built frame for about $10,000.

“We knew that if we could find the axles and the engine we wanted, we could build it,” Maurice Steiger told the Grand Forks Herald in 1958.

Douglass went to E. O. Peterson, the president of the Union State Bank in Thief River Falls, Minnesota, and presented his options to the banker. He explained to the banker he could either buy a Wagner for $24,000 or build a tractor using a hand-built chassis and used parts for about $10,000. According to Douglass, the banker said, “I think you should try to build one,” and he set up the Steiger family with a loan.

The original intention had been to build a smaller tractor, but the plan evolved. “We really didn’t plan to build such a large one,” Douglass said. “But once we got started, we couldn’t seem to stop.”

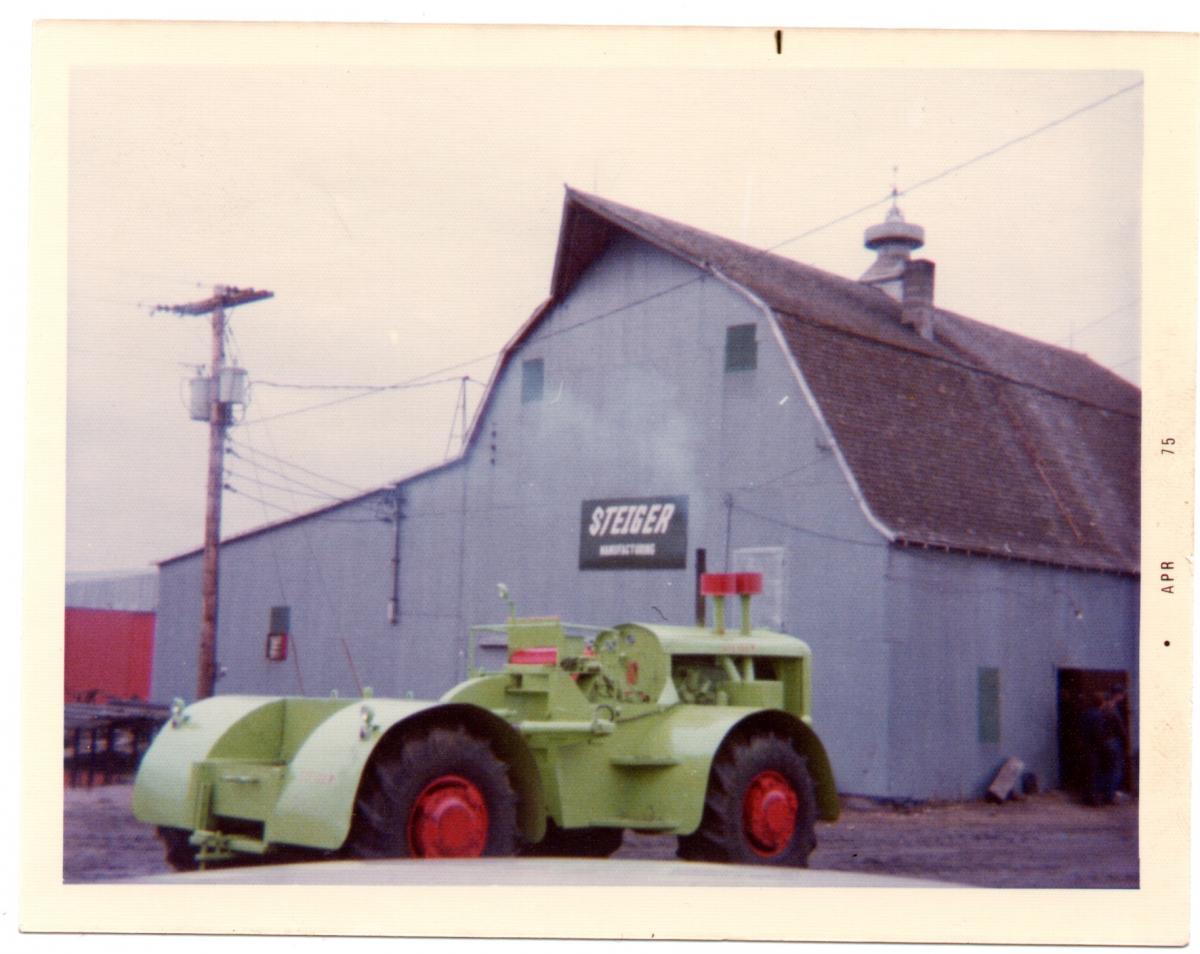

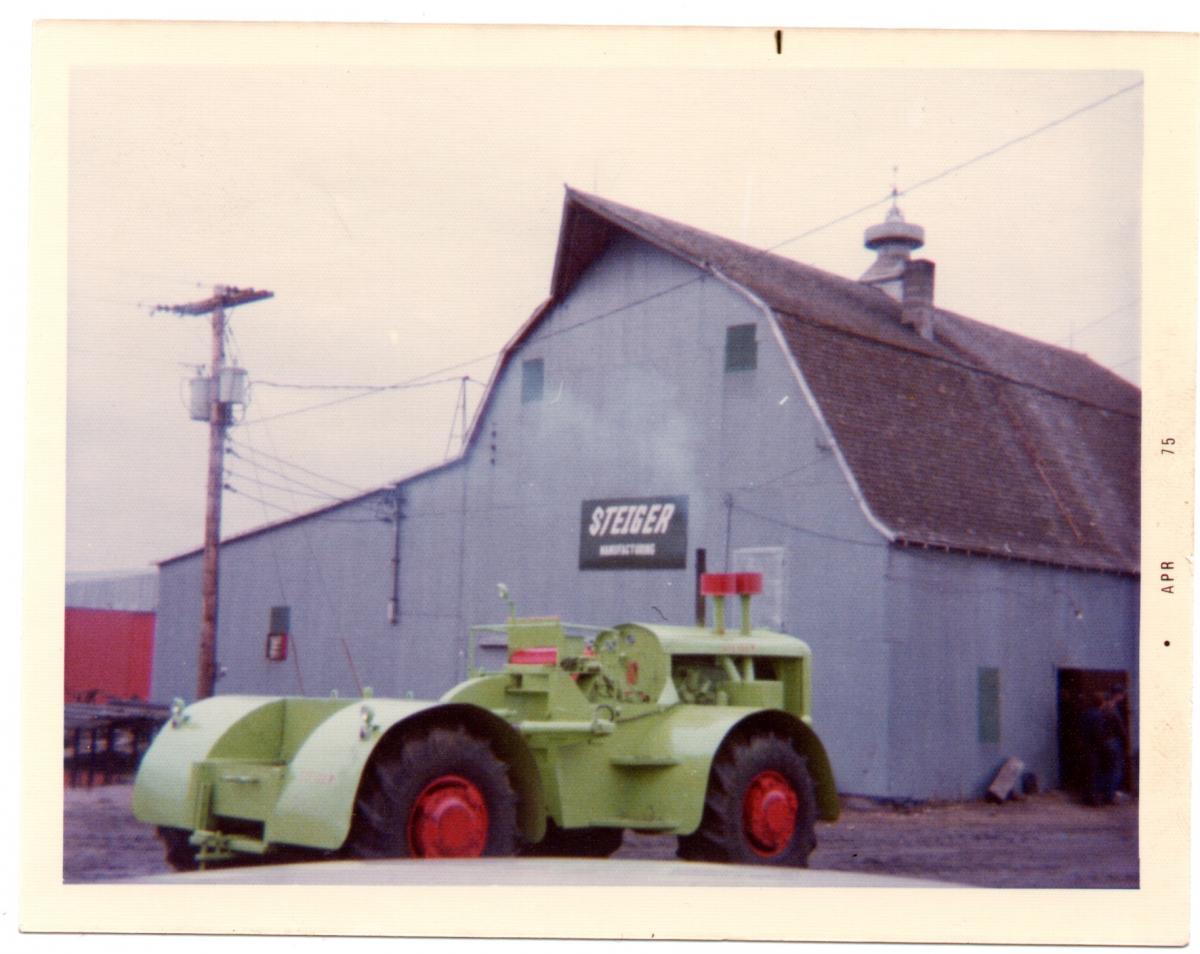

The shop where the machine was built was the former dairy barn on the Steiger farm, which had been converted to a shop after they sold off their cattle. In the photographs of the shop that appeared in local newspapers, the walls were covered with light paneling or sheetrock, and the space was barely large enough to fit the tractor.

The Steigers went to work on the project in the fall of 1957. They scrounged used parts from mining equipment used on the Iron Range of northeastern Minnesota. For this first machine, some of the tooling equipment was improvised. John used a sledge hammer and a blacksmith forge to heat and bend an adapter ring that went between the engine and bell housings on the transmission. They used an electric 9-inch angle grinder to smooth down the weld seams for a cleaner finish. The engine was a diesel that had been used in an HD-14 Allis-Chalmers crawler. New tires and hydraulic components were purchased to finish the tractor.

According to Drache, they finished the machine in 57 days during the winter of 1958, and the material cost added up to $9,200. The tractor would become known as Steiger #1. Sometime much later, a Case IH employee dubbed the machine “Barney,” and that moniker stuck.

The lurid green paint color that first appeared on Steiger #1, incidentally, has a fair amount of lore surrounding it. A popular myth is that the family mixed the cans of paint they had on hand and used it. Douglass Steiger said the paint was selected because it was a bright color that was not being used in the agricultural industry. The green shade, he said on multiple occasions, was in-spired by the color used by construction equipment maker Euclid.

The only part of the drive mechanism that was custom-built was the power divider—the rest of the components were off the shelf (or salvaged from used machines). Steiger #1 had roughly 220 flywheel horsepower and could handle as much as three sets of five-bottom plows.

“In the spring of 1958, John was able to plow with 12 bottoms,” Drache wrote in Beyond the Furrow, “and in one 15-hour day the Steiger brothers cultivated 300 acres.”

Steiger #1 allowed John to work the family’s 5,200 acres of owned and rented land. “A farmer just cannot understand what a four-wheel-drive will do until he has driven one; it is so much more efficient,” Douglass said.

Douglass designed the tractor despite possessing no more than a high school education and no formal training in engineering or as a draftsman. “I never went through engineering or anything,” Douglass said. “I basically went through high school and had taken some architectural drawing like they do in high schools.”

The innovation displayed on the Steiger farm, whether in tractors or even just shop machinery, was remarkable. The Steiger #1 was worked hard for many years, was restored in 1975, and eventually retired to the Bonanzaville Museum in West Fargo, North Dakota.

Clifton Johnson did the math and was shocked at how long and hard that home-welded machine worked. “That old big one, I calculated it had been two and a half times around the world with plows behind it,” he said.

The Steiger men saw a problem, and they pursued a solution with fearless mechanical skill.

MaJeana Steiger Hallstrom said the entire community recognized their talent. “People kind of knew that if they went to one of those guys, they would be able to find a way to solve the problem,” Hallstrom said.

Johnson summed it up more simply. “Get a torch and a welder,” he said. “You can make most anything.”

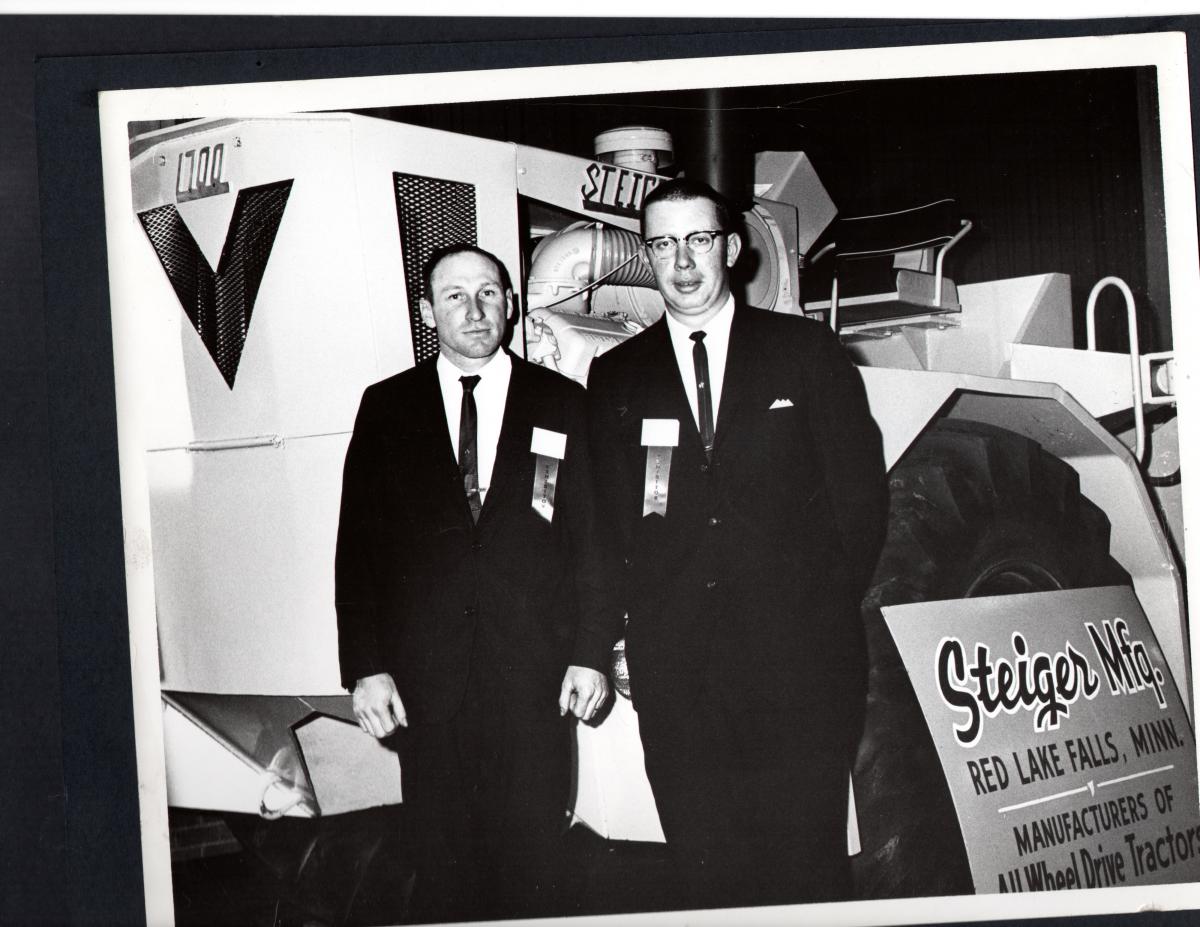

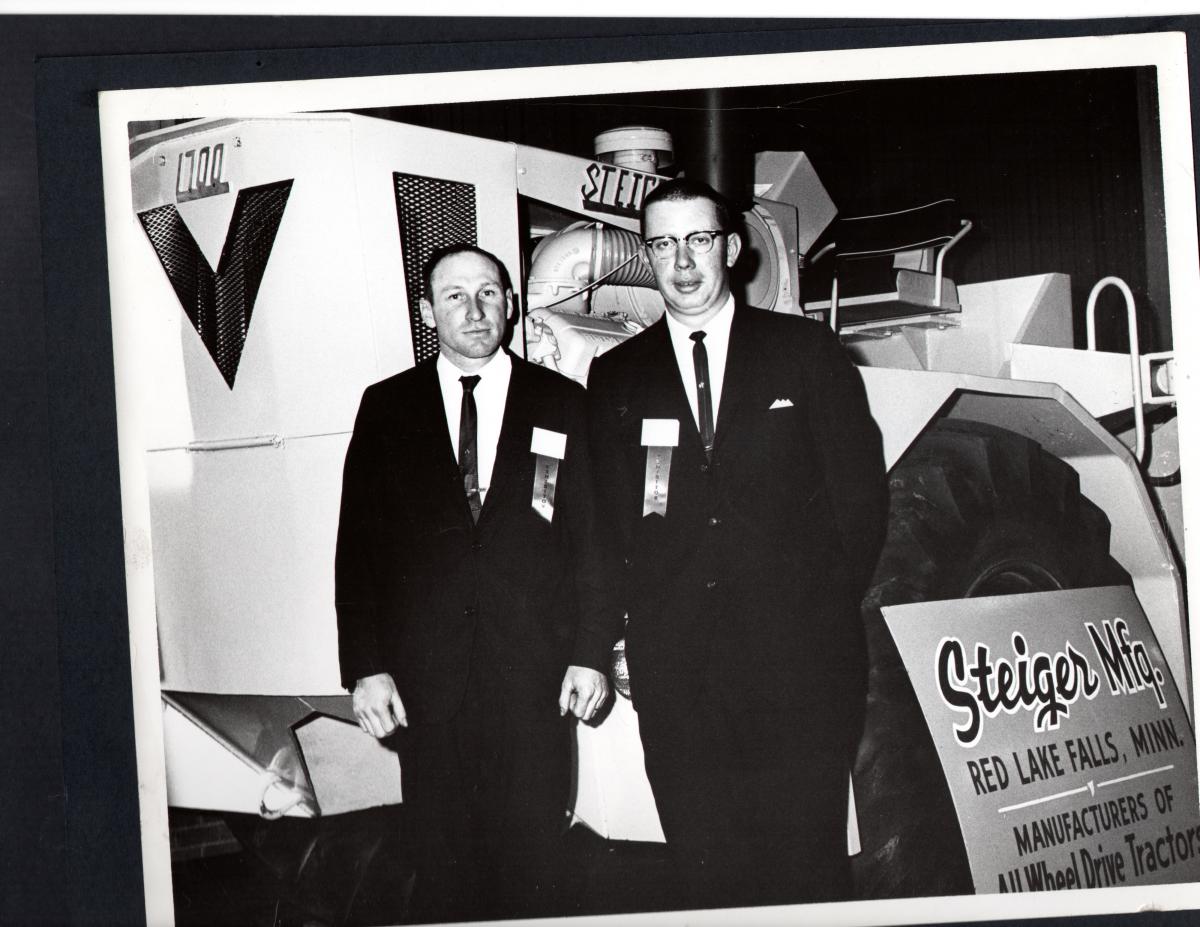

Douglass Steiger and Clifton Johnson with a 1960s era barn-built Steiger 1700.

The Steigers had built several other pieces of equipment for the farm, including two self-propelled swathers, a rock picker, and a 60-foot weed sprayer. The 24-year-old Douglass reasoned they could build their own four-wheel-drive tractor using used parts and a hand-built frame for about $10,000.

“We knew that if we could find the axles and the engine we wanted, we could build it,” Maurice Steiger told the Grand Forks Herald in 1958.

Douglass went to E. O. Peterson, the president of the Union State Bank in Thief River Falls, Minnesota, and presented his options to the banker. He explained to the banker he could either buy a Wagner for $24,000 or build a tractor using a hand-built chassis and used parts for about $10,000. According to Douglass, the banker said, “I think you should try to build one,” and he set up the Steiger family with a loan.

The original intention had been to build a smaller tractor, but the plan evolved. “We really didn’t plan to build such a large one,” Douglass said. “But once we got started, we couldn’t seem to stop.”

The shop where the machine was built was the former dairy barn on the Steiger farm, which had been converted to a shop after they sold off their cattle. In the photographs of the shop that appeared in local newspapers, the walls were covered with light paneling or sheetrock, and the space was barely large enough to fit the tractor.

The Steigers went to work on the project in the fall of 1957. They scrounged used parts from mining equipment used on the Iron Range of northeastern Minnesota. For this first machine, some of the tooling equipment was improvised. John used a sledge hammer and a blacksmith forge to heat and bend an adapter ring that went between the engine and bell housings on the transmission. They used an electric 9-inch angle grinder to smooth down the weld seams for a cleaner finish. The engine was a diesel that had been used in an HD-14 Allis-Chalmers crawler. New tires and hydraulic components were purchased to finish the tractor.

According to Drache, they finished the machine in 57 days during the winter of 1958, and the material cost added up to $9,200. The tractor would become known as Steiger #1. Sometime much later, a Case IH employee dubbed the machine “Barney,” and that moniker stuck.

The lurid green paint color that first appeared on Steiger #1, incidentally, has a fair amount of lore surrounding it. A popular myth is that the family mixed the cans of paint they had on hand and used it. Douglass Steiger said the paint was selected because it was a bright color that was not being used in the agricultural industry. The green shade, he said on multiple occasions, was in-spired by the color used by construction equipment maker Euclid.

The only part of the drive mechanism that was custom-built was the power divider—the rest of the components were off the shelf (or salvaged from used machines). Steiger #1 had roughly 220 flywheel horsepower and could handle as much as three sets of five-bottom plows.

“In the spring of 1958, John was able to plow with 12 bottoms,” Drache wrote in Beyond the Furrow, “and in one 15-hour day the Steiger brothers cultivated 300 acres.”

Steiger #1 allowed John to work the family’s 5,200 acres of owned and rented land. “A farmer just cannot understand what a four-wheel-drive will do until he has driven one; it is so much more efficient,” Douglass said.

Douglass designed the tractor despite possessing no more than a high school education and no formal training in engineering or as a draftsman. “I never went through engineering or anything,” Douglass said. “I basically went through high school and had taken some architectural drawing like they do in high schools.”

The innovation displayed on the Steiger farm, whether in tractors or even just shop machinery, was remarkable. The Steiger #1 was worked hard for many years, was restored in 1975, and eventually retired to the Bonanzaville Museum in West Fargo, North Dakota.

Clifton Johnson did the math and was shocked at how long and hard that home-welded machine worked. “That old big one, I calculated it had been two and a half times around the world with plows behind it,” he said.

The Steiger men saw a problem, and they pursued a solution with fearless mechanical skill.

MaJeana Steiger Hallstrom said the entire community recognized their talent. “People kind of knew that if they went to one of those guys, they would be able to find a way to solve the problem,” Hallstrom said.

Johnson summed it up more simply. “Get a torch and a welder,” he said. “You can make most anything.”

Douglass Steiger and Clifton Johnson with a 1960s era barn-built Steiger 1700.