The Cotton Man

From picking cotton by hand on his family’s farm, to growing the production of Buster’s Cotton gin from 1,100 to 116,000 bales over the course of thirty years, Dan Taylor has built his life around the cotton industry. Read about the man, his tractors, his many barns, and an addiction to preservation.

This original article was published in celebration of the 2018 Red Power Round Up held in Montgomery, Alabama, from June 13–16. The 2018 event was cotton-industry themed.

“Twenty-seven bales of cotton’s a pretty big piece of bus’ness, Mr. Vicarro.”

—Tennessee Williams, Twenty-seven Bales of Cotton

The sun casts a baleful eye on Blum, Texas during cotton-picking season, roasting those bent over the rows with more than 100 degrees of unfiltered solar rays. Pickers have to wear gloves, as cotton plant stems will transform bare hands into a bloody mess. And if you can’t afford good gloves, the plants will tear your wrists up just as quick.

Dan Taylor spent most of his youth bent over cotton plants. He grew up on a cotton farm near Blum, which is about 55 miles south of Fort Worth. Mechanization was improving life on the farm and oil was making Texas fat, but the farming revolution and black gold both skipped over the shallow clay soil and short grass of Blum, and most of Hill County for that matter.

In 1950, the high school graduation rate of Hill County was 11 percent. Family farms were failing, and the area had no oil reserves worth tapping. Population dropped steadily as people left to work the stockyards in nearby Fort Worth, or do almost anything else.

Dan Taylor’s father was not one to quit. He had grown up farming cotton, and he was damn sure going to continue working his small plot of land. His neighbors and friends might move on. He had put down roots in the shallow clay soil and short grass of Hill County. His cotton farm was what he had and what he did and would do.

Which meant everyone in the family pitched in and made the best of the modest income that resulted. Taylor’s mom sewed every single cotton sack used for harvesting. When the knees wore out in the boys’ pants, they had to patch them. The family grew up sweating and straining in his father’s cotton fields in 100-degree summer heat. In fact, the Taylors picked the cotton by hand until Dan was a sophomore in high school.

Left: The Taylor place is located on a 10-acre plot not far from Lubbock, Texas. Dan and Linda raised three children not far from here, and all have grown up to be involved in agriculture. His son-in-law, Thomas Hicklen, farms 3,750 acres of cotton in the Lubbock area. / Right: Dan Taylor spent 11 years teaching agricultural education before he turned to running a cotton gin. He farmed on the side, and bought this 1953 Farmall Super M to help on his spread. Lee Klancher

Left: The Taylor place is located on a 10-acre plot not far from Lubbock, Texas. Dan and Linda raised three children not far from here, and all have grown up to be involved in agriculture. His son-in-law, Thomas Hicklen, farms 3,750 acres of cotton in the Lubbock area. / Right: Dan Taylor spent 11 years teaching agricultural education before he turned to running a cotton gin. He farmed on the side, and bought this 1953 Farmall Super M to help on his spread. Lee Klancher

Taylor also logged long days on the back of a tractor, and started driving at age 7. The only way he could reach the clutch was to slide down the seat and wedge all of his weight onto the pedal. “It’s a wonder we’re alive,” Taylor said.

The tractor was something the young man enjoyed, so much so that he would collect dozens of the machines later in the life. The long days hoeing, picking and tending to cotton fields also made a powerful impression on the young man.

“Too much manual labor,” Taylor said of the time, “and not enough tractor driving.”

By the time Taylor graduated from high school, he only knew one thing for sure about his future. He was going to do anything but farm, and would have nothing to do with cotton.

One year at North Texas State in Denton changed Taylor’s perspective. He found himself surrounded by people who didn’t understand his way of life. His urge for a new way had led him to a place in which he found no common ground with the students or the curriculum. The young man transferred to Texas Tech in Lubbock, Texas, hoping to find something more hospitable.

He moved to Lubbock, and rented a room on a farm outside of town. He took a job on a farm to help make ends meet. The area and the institution suited him perfectly.

He found himself enamored with the farming techniques used in Lubbock, which used heavy irrigation and more equipment to farm larger spreads. As he came to realize that farming didn’t have to be the life he knew as a boy, he also grew to understand that he loved working the land.

The inside of the main barn is set up as a workshop. Taylor is constantly restoring either a tractor or ginning equipment. Lee Klancher

The inside of the main barn is set up as a workshop. Taylor is constantly restoring either a tractor or ginning equipment. Lee Klancher

He changed his major to agriculture education. He met his wife, Linda, who was also studying at Texas Tech. After earning his master’s degree, he taught agricultural education at Lubbock Cooper high school. The two were married in 1964 and settled near the school. Linda finished her schooling and graduated in 1965. Taylor rented a 10-acre farm, and added a few more acres during the next decade. He grew cotton on the school farm, and bought a used 1953 Farmall M to work the land in 1967. Despite his convictions in high school, he was back on the farm. And loving it.

Teaching was also something that Taylor enjoyed tremendously. He led his students to a number of appearances in the Texas state competition in parliamentary procedure, and a number of his students went on to win national awards in a variety of competitions.

“I loved teaching and I loved the students,” Taylor said. He taught for eleven years, and enjoyed every minute. But Taylor’s interest in farming began to overwhelm his desire to teach. By the mid-1970s, however, farming was not profitable enough to provide a start-up entrant a good living.

Buster McNabb owned Buster’s Gin, which was based in nearby Ropesville and had been ginning cotton since 1947. McNabb took a liking to Taylor, and offered him a portion of the business if he would run the operation. Taylor thought about the offer for about a year before accepting. In the end, he did it so that he could put more time into farming.

“That was my reason for leaving teaching,” Taylor said. “It was probably the hardest decision of my life.”

Taylor started working for McNabb on a handshake deal that allowed Taylor to purchase a 25 percent share of the business. He began running the gin in 1975, and slowly bought it off McNabb over the next nine years. When Taylor started at the gin, business was slow. He was a natural salesperson, mostly because his love of farming and the region was genuine and deep.

Buster’s Gin is a long-time fixture of Ropesville, Texas, and was founded in 1947. Taylor left teaching to run the gin from 1975 to 2009. While running the gin, Taylor and his family operated a cotton farm. Taylor is a self-admitted pack rat of a collector, and has thousands of items housed in his barns, shed and museum. This bar was in Buster’s Café, which served workers at Buster’s Gin for many years. Lee Klancher

Buster’s Gin is a long-time fixture of Ropesville, Texas, and was founded in 1947. Taylor left teaching to run the gin from 1975 to 2009. While running the gin, Taylor and his family operated a cotton farm. Taylor is a self-admitted pack rat of a collector, and has thousands of items housed in his barns, shed and museum. This bar was in Buster’s Café, which served workers at Buster’s Gin for many years. Lee Klancher

Taylor’s care for the product and his clients brought in new customers and he served them well by upgrading the gin’s equipment. The business grew steadily under his leadership. In 1974, Buster’s Gin processed 1,100 bales of cotton. In 2007, the company turned 116,000 bales.

The growth came during a competitive time for cotton gins. In 1975, Hockley County had 34 operating cotton gins. By 2010, only seven remained, and they process more cotton than 34 did back in the 1970s. Production speeds changed during that time, and a gin that could put out four or five bales in one hour was upgraded to doing sixty bales in an hour by the turn of the century.

“We survived the fallout. We were growing while a lot of our neighbors were going out of business,” Taylor said. “It’s not always about price. It’s dealing with people.”

Taylor believes that a key to succeeding in agriculture is relationships.

“You can’t have a Walmart mentality in agriculture,” Taylor said. “There are some personalities there and you have to have some feel for your customers.”

Taylor didn’t forget his teaching roots. When he renovated Buster’s Gin, he added a viewing room. Groups of students and adults pass through, and can view the gin in operation from a room above. Taylor led tours, and had a video produced that explains how cotton farming is done at his outfit.

As his role at Buster’s Gin increased, Taylor and Linda bought a farm and more acreage. They spent 20 years on that farm. The farm was on an unimproved road. Lubbock is located in the South Plains, and winter conditions are cold and blustery. The area gets about 10 inches of snow each winter, and occasionally is hit with heavy snow. When that happened, Taylor and his family would traverse the 4.5-mile-long unimproved road out to the highway with a tractor, at least until the plow made it out to their place.

Dan Taylor’s place near Lubbock, Texas has three large buildings. One is a shop and barn, another is a cotton gin museum, and this one is used to park cars and tractors. The 3010 worked on the Taylor farm since the 1970s. The working barn is used to store tractors and house a shop. The barn is cleaned out several times each year to host events. The place has a roomy loft above the shop, and comfortably seats 125 people. Lee Klancher

Dan Taylor’s place near Lubbock, Texas has three large buildings. One is a shop and barn, another is a cotton gin museum, and this one is used to park cars and tractors. The 3010 worked on the Taylor farm since the 1970s. The working barn is used to store tractors and house a shop. The barn is cleaned out several times each year to host events. The place has a roomy loft above the shop, and comfortably seats 125 people. Lee Klancher

The place was a fairly utilitarian, if comfortable, home. While the Taylors lived on that farm, there wasn’t much room for Taylor to work on equipment. Machine maintenance was done outside. The farm was home for the Taylors while they raised three children, DeLinda, Darrell, and Davon.

In 1993, the couple decided that they needed to move somewhere more accessible. Taylor bought 10 acres on a corner, not far from Lubbock. They built a new house, and shortly after, Taylor built his barn.

“I always loved barns and loved the ones that looked like Midwestern barns,” Taylor said.

The barn is outfitted with plenty of room to store tractors, and large, well-lit shop. He began to fill it with antique tractors and collectibles. He had several tractors, including the 1953 Farmall M he bought in 1967, and a John Deere 3010 that also had served on his farm.

One of Taylor’s fixations is preservation. Since he was young, he loved to keep things. He would remember who gave him each and every present he received, and wanted to keep every single thing.

This naturally led him to accumulate things. As owner of the cotton gin, he found himself coming across all sorts of old equipment and signs. As people came to know he liked to keep things, more and more things came his way.

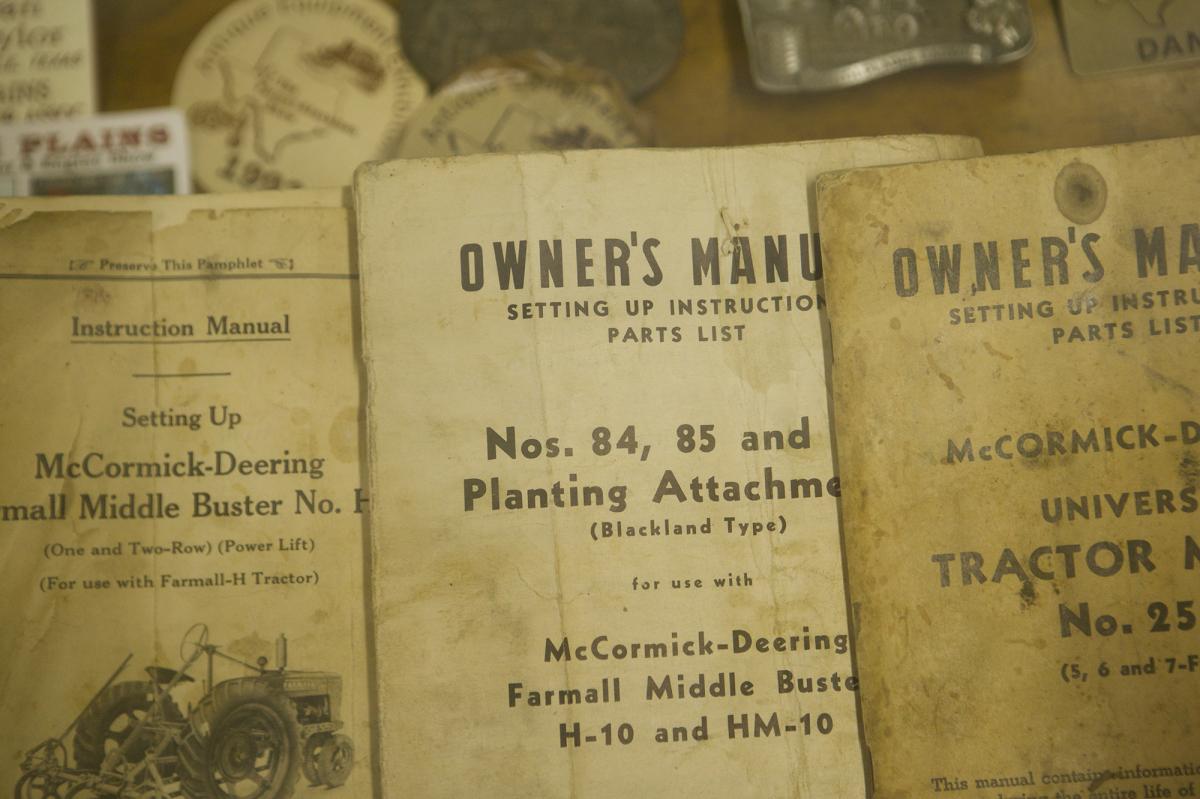

The collection in the museum includes thousands of pages of records, including owner’s manuals for implements and equipment. Lee Klancher

The collection in the museum includes thousands of pages of records, including owner’s manuals for implements and equipment. Lee Klancher

His collection today includes a vintage diesel engine, gin equipment, ledgers and other records from cotton gins, piles of literature, books, and a small working cotton gin model. He has a 1875 Smith Gin Stand used at the gin in Lukenbach, Texas. He also owns a teletype machine that was once connected to the New York Cotton Exchange and the bale of cotton that was present at George Bush’s 2000 inauguration.

So his new barn filled up quickly. Taylor describes his condition as an addiction. He isn’t much of a drinker but he imagines that his fascination with collecting is akin to an alcoholic’s thirst for booze.

“With collecting,” he said “You are always wanting another one.” That thirst also applied to barns. In 1998, Taylor decided that he needed to have another barn. He built the porch barn, which is Linda’s favorite.

“I built a lot of barns once I started building them,” he said. He added a heated shop on his old farm, which is the headquarters for a working farm. And he continued to acquire things—antique farm tractors, and acres of cotton gin equipment and memorabilia.

“I collected so much stuff, I thought I needed to get it all in one location,” Taylor said. So he built the cotton gin museum. He initially thought the building was too large. Now, of course, it’s completely full and he wished it were larger.

This 1908 Fairbanks-Morse one-cylinder diesel engine was used on a cotton gin owned by the McNabb family. The engine runs, and is started for special events at the Taylor museum. Lee Klancher

This 1908 Fairbanks-Morse one-cylinder diesel engine was used on a cotton gin owned by the McNabb family. The engine runs, and is started for special events at the Taylor museum. Lee Klancher

The museum is full of old equipment, and Taylor keeps it open for the events he hosts at his place. With all the space he has available, he can move the tractors out into the yard and seat 125 comfortably in his original “Midwestern” barn. The guests roam the grounds, checking out his tractors and the museum.

Taylor continues to dream of new buildings. His latest project is building an “old-timey” cotton gin office. He also intends to see some of his vintage equipment put to use, and plans to set up a working gin using turn of the century equipment.

Despite his time farming in the hot Texas sun with hands bloody from picking cotton, Taylor’s love of farming led him to a life with cotton. His Lubbock spread is a testament to a passionate life of teaching, business, and a deeply held love for the land.

A crew of four men using a tractor and a post-hole digger constructed this shed in only four days. They worked with pre-fabricated trusses and material that was shipped in ready to assemble. The concrete pad was poured ahead of time. Lee Klancher

A crew of four men using a tractor and a post-hole digger constructed this shed in only four days. They worked with pre-fabricated trusses and material that was shipped in ready to assemble. The concrete pad was poured ahead of time. Lee Klancher