The Color of Your Blood

Robert P. Corley invested 25 years of blood and sweat into his International Harvester Company dealership near Decatur in central Illinois. In November 1984, news hit that Harvester’s agricultural division was to be purchased by Tenneco. While this meant the company would survive, the fact that Harvester would be merged with Case was downright terrifying for those who had imprinted the brand on their DNA.

When Corley spoke to the New York Times in November 1984, he had been sent airline tickets from Case to attend the dealer announcement in Dallas, Texas. He was doubtful that what was to come would be good for his business. When told that Dr. Glenn W. Kahle, the former head of IH’s agricultural division, was part of the merged team, he remained skeptical.

“My concern is that his blood is Case orange now, while ours is Harvester red,” Corley said. Corley had cause for concern. According to a November 1986 article in the Chicago Tribune, the purchase gave Case IH 2,700 dealerships in North America. Once the dust settled, Case IH would have only 1,600 dealers in the United States.

Corley would have been aghast to learn that Kahle came to Harvester from Deere & Co. Kahle may have been a John Deere engineer in a former life, but his blood, however, was pure red. He grew up on IH equipment and remembers strapping a block of wood to the clutch pedal of his dad’s Farmall Regular so he could drive it when he was just seven years old. He left Deere after a very successful 24-year career. “When I got to IH, it was like I walked into a high school reunion. The people were just wonderful. Like family,” Kahle said. “It was really an exciting, opportune time. To this day, it was probably the best experience of my life.”

Brand loyalty ran very deep with IH and, for that matter, Case. Both brands’ founders had roots that went back to the 1800s, and both had loyal fan bases. Harvester had more tractors on the market and a dealer network twice the size of Case’s. Harvester also was sitting on a mountain of new technology developed during the McCardell era and had a gorgeous research and engineering facility at Hinsdale, known at that time as Burr Ridge.

The perception and understanding of the “merger,” however, was that Case had bought Harvester. The two companies were competitors, and Harvester had always had the upper hand in market share. After the acquisition, the internal politics became entrenched and difficult. Tenneco CEO James Ketelsen had to figure out how to mix colors and create a team that could find a way to survive the toughest time on the farm in history.

One of the trickiest parts of his job would be creating a blended engineering team. Engineers at that time didn’t socialize with other colors.

A few days after the sale was made official, a team of Case managers went down to Burr Ridge. They brought the Harvester team leaders into the conference room and told them that the engineering center at Burr Ridge would be closed and some of the engineers would move to Racine and the rest would be let go.

Kahle managed to convince Ketelsen to come down and tour Burr Ridge before closing it. In fall 1984, Ketelsen met Kahle for the first time in person. He showed up in style.

“He flew into Hinsdale in three helicopters,” Kahle said. “They landed right outside my office in Hinsdale. They were in formation—he was in the front helicopter. His helicopter set down first and the other two landed behind him. It was like the Queen of England or the Pope came to visit.”

The engineering headquarters for Case IH was originally going to be located in Racine, Wisconsin, but the former IH engineering team convinced Tenneco CEO James Ketelsen to visit Hinsdale (or Burr Ridge, as it came to be known) before closing the facility. Ketelsen and his team flew in from Houston in three helicopters. Glenn Kahle collection

At the time, Kahle was aware of Ketelsen’s intentions to close the Harvester engineering center and move the engineers and staff to Racine. He took Ketelsen on a three-hour tour of the facilities. He had his key people stationed throughout the plant, showing off upcoming projects and the facilities.

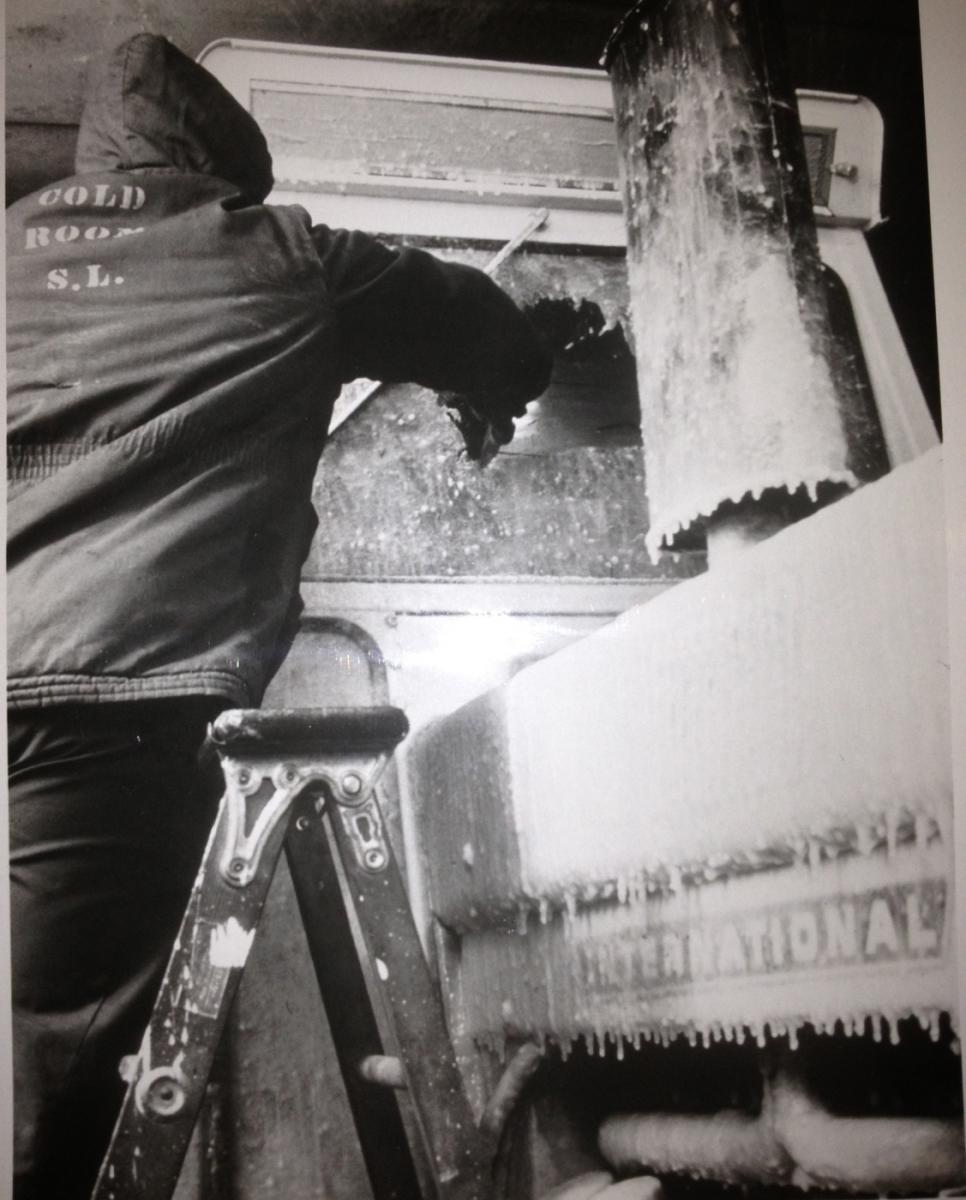

He saw the climate-controlled chamber big enough to hold a tractor that could be cooled to minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit to test cold-starting. He saw rooms with salt baths that could simulate 40 years of bad weather to test electronic components and corrosion. He saw an acoustic chamber filled with noise generators and used for noise measurements. In it, the Harvester engineers had a new cab.

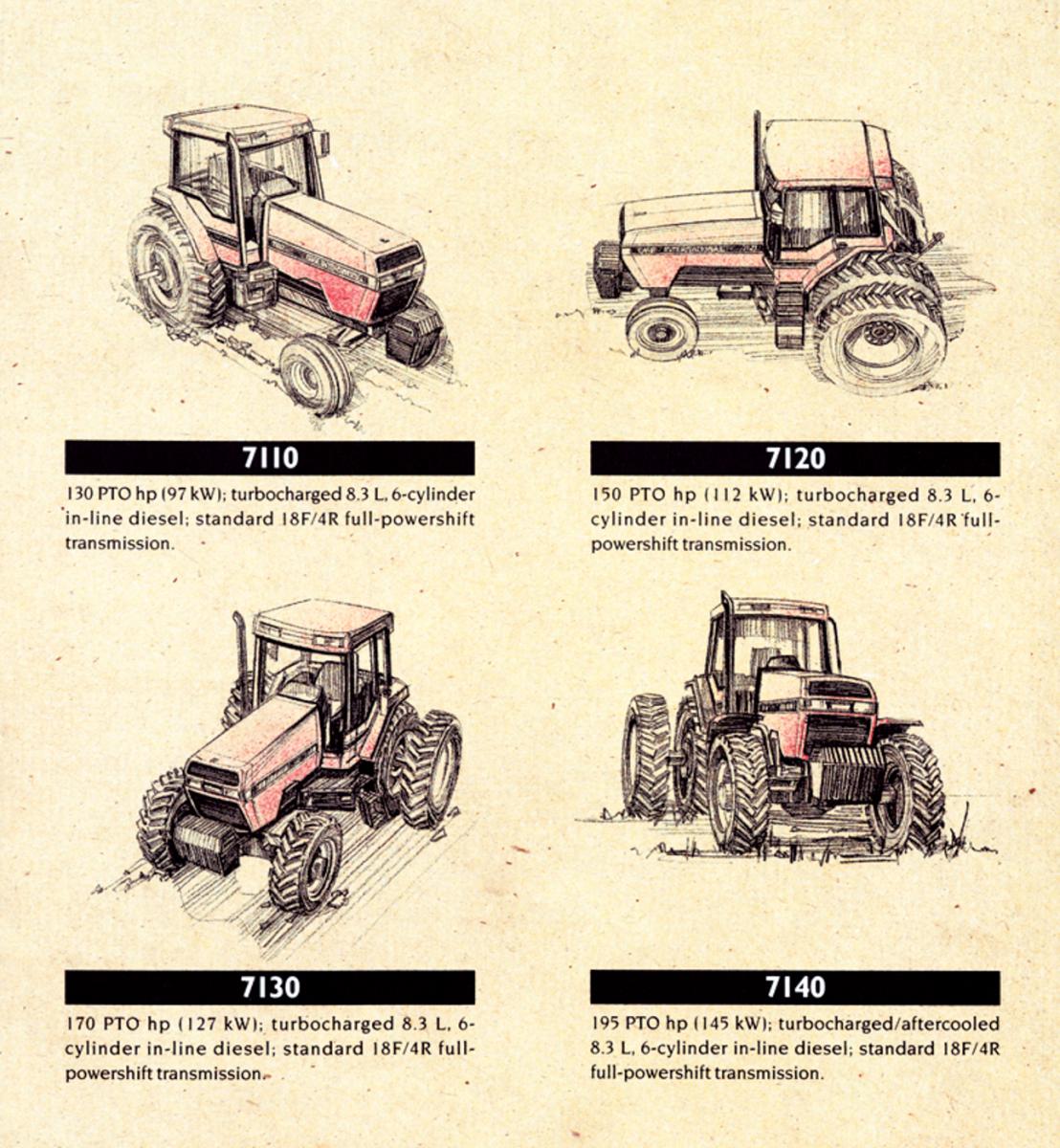

Early Magnum sales materials. CNH Global

“Cab noise measurements at that time were about 100 dBa,” Kahle said. “We had one that was 82 or 83. Getting in was like setting out in space. He got in and out of that one about three times.”

There was also plenty of new technology on the drawing boards, created by a prolific, well-funded Harvester engineering team that was generating 30 to 50 patents each year. The engineering team’s production guaranteed nothing, and there was plenty of concern about what would happen with the engineering staffs.

Ben McCash was a shift supervisor in the engineering test department. He recalls the time as an uncertain one. “The question for some time was, ‘Okay, whose tractor design is going to do what?’ Because the first thing they did was stop production at the Rock Island plant, which was the main one that we dealt with. So there was uncertainty on our part as to whether they were going to go ahead with our designs or go ahead with the designs that Case was manufacturing at Racine.”

Ketelsen got back in his helicopter and went home. The next day, he declared that the Case engineering team would move to Burr Ridge. Kahle was named the head of the new engineering team. This was fairly unusual, as most of the high-level management positions were assigned to people from J. I. Case.

“I was literally the only office of the company that actually transferred from IH to Case IH. I was the only vice president, I’m sure,” Kahle said. “That worked because I’d come from Deere and had some background from both companies. Plus Case tried to hire me in 1978.”

McCash had an endurance test running 24/7 during the merger, and doesn’t recall much of an impact on his group as a direct result of the change. “But again, more than 90 percent of the International Harvester Engineering staff in the tractor area were carried over by the merger,” he said. “So there was not a big impact at that time. The biggest impact was always wondering, okay, what’s going to happen next?”

When Kahle visited the Case engineering facility, he found a cartoon on the wall that depicted the Case eagle being knocked over with IH on top. He had his work cut out blending the team.

“There was always, for several years, what we called ‘Us’ and ‘Them.’ So there would always be some controversy as to which way to do things. Everybody liked their own way of doing it,” McCash said. “For some people it never went away.”

Case had developed a strong testing program, and Kahle adopted that for the blended group and put the Case test supervisor Eldon Brumbaugh in charge.

The research and engineering facility at Burr Ridge would thrive after the merger, but another Harvester icon would not. The manufacturing facility at Rock Island, Illinois, was closed. The decision was particularly tough on Ketelsen, who grew up in nearby Davenport, Iowa. Illinois Governor James Thompson, the Chicago mayor, and a host of politicos visited Ketelsen, hoping to change his mind. He remained steadfast—Rock Island was too old and cumbersome. The plant built to produce the original Farmall would be shuttered and sold.

Ketelsen’s tour of the engineering and test facilities at Burr Ridge convinced him to centralize the new company’s engineering there. He was particularly impressed by this room, which allowed engineers to test tractors at temperatures well below freezing. This image was taken with the tractor cooled to 20 degrees below zero. Wisconsin Historical Society

Plant and dealer closings are tough business, but some fome fairly basic issues proved to be nearly as problematic. The first was to develop a new name and logo. According to Gerry Salzman, a number of options were considered. The name International Case was suggested, as was a logo that used the C from the early-twentieth-century IHC logo.

“Instead of ‘C’ being ‘Company,’ they were trying to look at ‘C’ being ‘Case,’ which, again, that came out of the International legacy and might have been a little too strong for some management at the time,” Salzman said. “But that was one. I know they played with a lot of different logos. But Case-International just kind of ended up after a lot of negotiations being the right one. So it wasn’t International Harvester, it wasn’t Case Company, it was Case-International.

“And you think, oh, these are not big deals. These were huge deals . . . you had all kinds of reactions. But at the end of the day, the name was probably an easy one.”

The second decision was the color. Salzman said that did not go easily.

“The management at that time was actually considering maintaining the Case colors, and there was a lot of research done. And when you look at it from a dealership standpoint, more dealers were originally International Harvester dealers than Case, so there was a lot of emotion about red versus yellow or cream or whatever the color was at the time [that] Case had.”

The new name and color were introduced at a big dealer meeting in Las Vegas held in February 1985. For guys like Corley, the Illinois dealer concerned about the color of Kahle’s blood, this was their introduction to the new line of machines they would have to sell in order to feed their families and employees. Salzman remembers the first Case-International tractor was put into a giant crate on stage and surrounded by a halo of smoke.

“The lights went down and the smoke was going and the music was at a fever pitch,” Salzman said. “Then all of a sudden this box lid started to move a little bit. Then it started to open up a little bit, and then eventually the box sides flipped down and there is a red tractor there.”

The color was a shade of red, but everything else was wrong. The tractor in the box was a Case painted red, with Case-International decals on the side. The decals had “Case” in much larger type than “International.” Very few of the dealers in the audience were satisfied. The Case people didn’t want a red machine, and the Harvester folks weren’t excited about trying to sell rebadged Case tractors.

“There were some dealers that actually started crying because they really thought they were going to lose their total identity,” Salzman said.

Even keeping red was a difficult fight. Salzman said that red was the right choice from a purely pragmatic standpoint.

“To be honest, if you’re trying to stand back and squint and be totally objective, there was stronger brand alignment toward IH than Case,” Salzman said. “Only because towards the end of Case, Case was pretty much a tractor supplier and that was it. They had combines, but their share was not very high. They just didn’t have a full line of equipment, and I think that’s what Tenneco saw in this merger as being able to put together and be a dominant force, not just on the tractor side. So those first two decisions of name and color really set the tone for the brand from there on out. And a very strong legacy.”

The legacy needed to be strong, because the market was anything but. Stagnant crop prices and high interest rates were driving farmers to foreclosures in record numbers. A 1986 university study found that one-third of all Iowa farms were insolvent. In Minnesota, rural schools closed so kids could go to a rally at the capitol in St. Paul with their farming parents to advocate for a moratorium on foreclosures. The situation was dire, and experts predicted as many as six more years of a down farm economy. Government farm policies weren’t helping and new ones being discussed weren’t expected to be any better.

Selling tractors in such an environment was an impossible task, and Case-International lost $214 million in 1985. While Tenneco CEO Ketelsen had expected a modest loss, the results were worse than he expected, causing him to quip, “A crow can make a bigger deposit than a farmer can.”

Ketelsen met with Kahle to discuss what he could do going forward. Kahle told him they had a new 100-plus-horsepower tractor on the drawing board. They had a new synchronized transmission and some other bits good to go. Not to mention lots of ideas—including a brand-new cab design—that Harvester hadn’t been able to fund.

“How soon can we get it out?” Ketelsen asked.

Kahle said two years and, as best he could determine, about $40 million were required to finish the work on the new model. Ketelsen quickly agreed, giving Kahle a fistful of dollars and a mandate: transform the final Harvester tractor into the first new tractor produced by Case IH.

For the employees who made a living wage making the machines, the dealers who survived by selling and servicing them, and the farmers who fed their families using the machines, times remained very hard. Fresh new blood in the form of a class-leading machine was necessary for any of these groups to maintain their way of life.

The Magnum would prove to be exactly what was required. With a great new look, innovative internals and well-tested components, the Magnum was a resounding success. The tractor’s fuel economy was outstanding. The look was strong and bold, and the reliability was solid out of the box—and outstanding once the team perfected the normal glitches that arise on a brand-new model.

The Magnum tractor combined the Cummins engine with a full-powershift version of the 50 series transmission. The result was a new industry standard. Many longtime employees say the Magnum saved the company. CNH Global

“The transmission was definitely a strength of the tractor,” McCash said. “I moved away from working on the Magnum, I started working the Maxxum, and I was away from it for some number of years. But when I came back to that I found out that our dealer system really didn’t know how to work on a Magnum transmission because they had almost never had any need to go inside of them.”

Steve Warner echoed the feeling of many long-time employees: the Magnum was a savior. “The product saved the company, quite frankly. Because in the end, both brands . . . there was enough of that tractor that they felt it was theirs . . . and after the first year of production, it became really a bullet-solid vehicle. I mean, just great, great reliability and durability.

“I saw a Magnum down in Argentina that had spent its whole life pulling a five-shank deep ripper—it’s all it ever did.” The ripper was used to break up soil compaction in irrigated cotton fields, a use that requires a ton of torque and power and beats up the tractor’s drivetrain. “It had 21,000 hours on it and they had brought it back to the dealership because somebody was hauling it on the truck and hit a tree and busted up the hood. And that was the first time that tractor had ever been to the dealership for anything. Twenty-one-thousand hours of nothing but ripping. That goes a long way to the testament of that tractor.”

Kahle has an early Magnum on his farm. He also has met folks with high-hour Magnums which required very little maintenance. He believes that their longevity is a result of the extensive testing and tooling done by his team of engineers. “The reliability part was probably the best thing we brought to the table.”

Warner credits Kahle’s leadership as key to the success of the Magnum engineering. “[Kahle] managed to do something that was really neat, and that was to pick the best pieces of the Case and the best pieces of the IH, not only the product designs but the technical capabilities and the people who could lead, and he’s really the one that was the father of the Magnum, in my opinion,” Warner said. “He was able to keep the two tribes from killing each other and, instead, going out and creating this new tractor.”

The two tribes had to work together and put in long hoursto create the machine. Kahle takes great pride in his team. “It took a helluva lot of determination, let me tell you. [It took] a lot of sacrifice by a lot of people. It was not a one-man show by any means.”

The times were rough enough that the Magnum alone couldn’t save Case IH. The new model was introduced in August 1987—near the very bottom of the second-worst time in recorded history for the farmer. Throughout 1988, pundits and industry experts forecast resurgence and growth for the farm economy. Droughts and other forces kept that from happening.

Case IH leadership continued to project profits in the future, and they continued to be wrong. Case IH was losing money, and dragging down its parent company, Tenneco.

In 1988, 306 acres of farmland at Burr Ridge was sold to raise capital. The land had originally been a McCormick family property and the original Farmall was tested in those very fields.

Tenneco also sold off its gas and oil holdings for a record $7.4 billion late that year, giving them more capital. The divesture made Case IH the biggest entity in Tenneco. Case IH was also the only holding that was not making money.

The Magnum 7140 was the first Magnum model completed. Gregg Montgomery collection

Early in 1989, the losses at Case IH prompted reporter Pamela Sherrod of the Chicago Tribune to write, “Because of its poor showing, Case also has been labeled the company most likely to be sold by Tenneco.” Ketelsen denied the allegation in the story, but later stated that if Case IH did not turn a profit in 1989, they would indeed be sold off.

The original Magnum did all that was expected of it and more. The company’s survival would be dependent on a farm resurgence. But Case IH had loaded their larders with an agricultural weapon that was good enough to overcome the doubts of those who saw the world through paint colors.

“The success of that tractor saved the company, and it not only saved it but it solidified us as a true company, it brought the two sides together,” Warner said. “Both the Case dealer and the IH dealer or the Case employee and the IH dealer could feel just as proud about that product as the other. And it really solidified our company.”

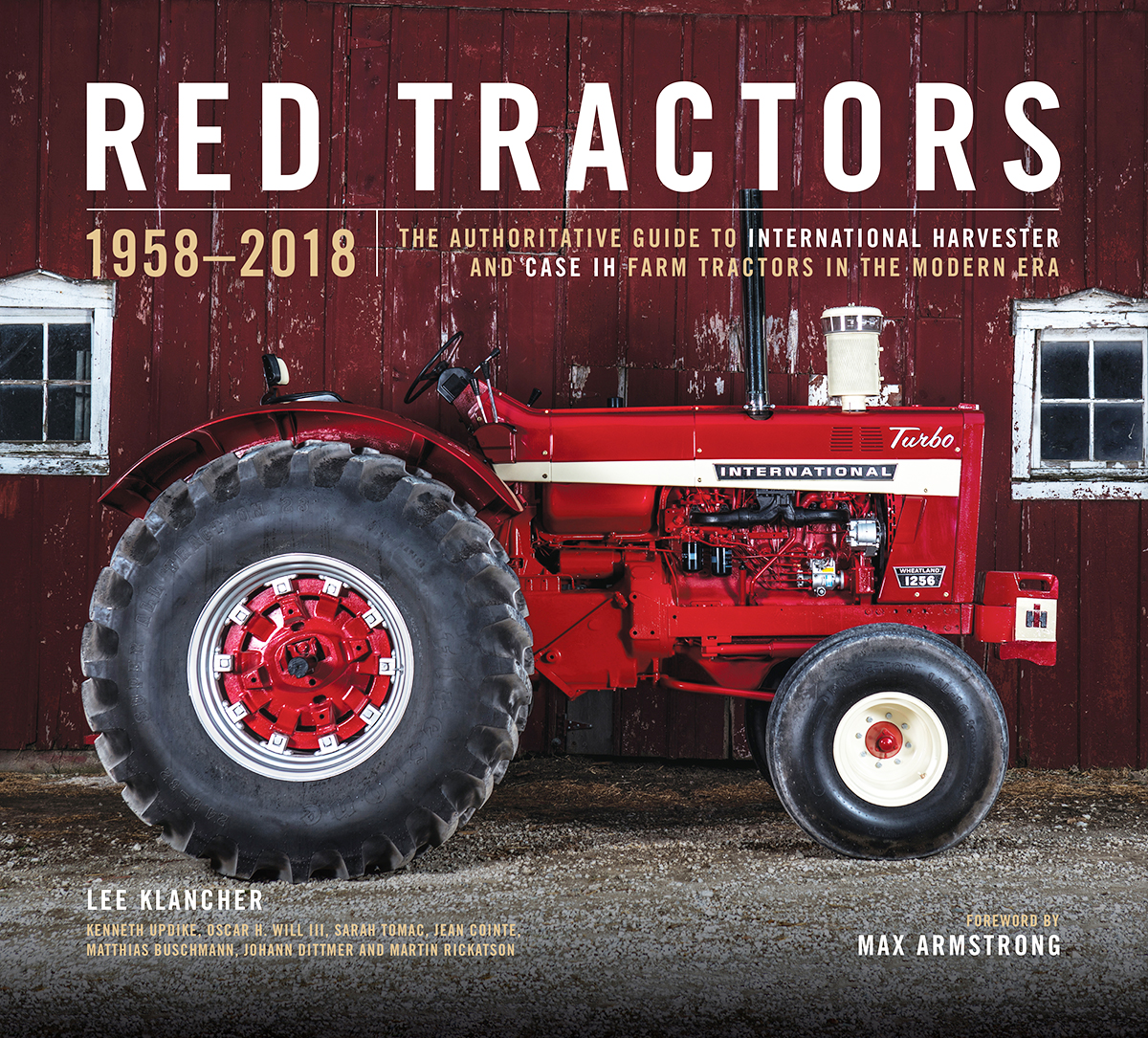

To find out the rest of the incredible story of International Harvester, get your copy of Red Tractors 1958–2018 HERE!

Previous Excerpt - Next Excerpt