Shooting History: Bright Lights in Dark Times

Are you curious to go back in time and explore some International Harvester history with author Lee Klancher? Keep reading to learn about the restructuring of IH under CEO Archie McCardell. This article was originally published as a feature in the Ageless Iron section of Successful Farming magazine, where Lee Klancher is a regular contributor.

Picking up the thread from the last post (Shooting History: Curveballs and Time Travel), let’s set the Wayback Machine to the mid-1970s, a few years after Brooks McCormick became the CEO at International Harvester. A descendant of the original founders and a lifetime employee of Harvester, McCormick led one of the most interesting periods in company history.

He stepped into a difficult situation at best. Harvester was saddled with immense debt, a capable if mildly staid product line, and a challenging labor environment while charging into the most difficult period in modern American history for heavy equipment manufacturers.

McCormick was a well-respected leader, despite the fact that he made a lot of unpopular changes in his efforts to turn around a lumbering giant. He ended light truck production, sold Wisconsin Steel, and—perhaps most controversially—hired Archie McCardell away from Xerox to become the Harvester CEO.

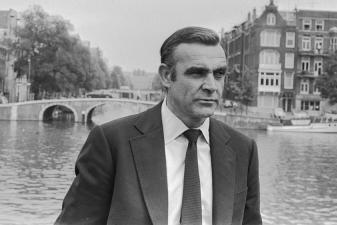

This image from the Wisconsin Historical Society shows Archie McCardell, who joined Harvester in August 1977 and soon moved up to CEO. A charismatic leader, he oversaw the most tumultuous portion of Harvester's history.

This image from the Wisconsin Historical Society shows Archie McCardell, who joined Harvester in August 1977 and soon moved up to CEO. A charismatic leader, he oversaw the most tumultuous portion of Harvester's history.

McCormick spent months attempting to lure McCardell, and had to pay dearly to reel him in. Harvester gave McCardell an annual salary of $460,000, plus a $1.9 million signing bonus and a loan for $1.8 million at six percent interest. Adjusted for inflation to 2019 value, the package was worth $15.6 million, making McCardell the highest-paid CEO in America when he started in January 1978.

Paying CEOs vast sums of money is a trend that has grown exponentially since the 1970s, but its popularity has not. I personally find it hard to imagine one person being able to give that much value. Given the fact that Harvester was in shambles four years after McCardell left, there is no question that part of that blame should be laid at his feet.

McCardell was smart as a whip and, unlike previous CEOs, did not rise up through the ranks at International Harvester. I believe McCormick choose McCardell at least partially because of that. The company needed a shake-up, and a person from the outside could more easily identify and make dramatic changes.

McCardell did just that. He initiated a company-wide cost-cutting campaign, set his mind to battle the unions, and worked to get Harvester’s large departments to work together more closely and efficiently.

While today he is a popular scapegoat with historians, many of the executives who reported to him speak well of him. And the one thing he unquestionably got right—and many seem to overlook—was investing in technology.

The path he chose to put Harvester back on firm ground was to create a dazzling new array of machines. He lavished money on the engineering department, who quickly set to work designing new equipment that could allow the company to drive past its mounting debt load.

One of the harshest challenges for a heavy equipment company is research and development cycles, which require massive investment and years of engineering, design, and testing. History has consistently shown that the most successful machines come from long development cycles. The Axial Flow combine and the John Deere New Generation tractor line were both game changers, and each required a decade or more of research and development.

Harvester’s late 1970s investment in research and development would take about five years to bear fruit, which is a reasonable timeline for new machinery. Unfortunately, the timing of the release of their flagship line could not have been worse.

As part of the Pro-Ag line in 1976, the 986 had fresh styling with a nod toward operator comfort, which was marketed as a professional upgrade to the agribusinessman's office. Photo courtesy of Dwight Blok.

As part of the Pro-Ag line in 1976, the 986 had fresh styling with a nod toward operator comfort, which was marketed as a professional upgrade to the agribusinessman's office. Photo courtesy of Dwight Blok.

Everything looked rosy in McCardell’s first 18 months, with a strong farm economy propelling Harvester to record sales of $8.4 billion in 1978. As the booming farm economy roared into fall 1979, McCardell’s determination to break the back of the union would prove part of his undoing.

The times were difficult for all heavy equipment manufacturers, and organized labor was one of the key challenges. Harvester had historically been more labor-friendly than others, but McCardell decided the time was right for a hard-headed approach. His poor choices and tough stance led the International Harvester plants to strike in the fall of 1979, choking production to a near standstill. More than 35,000 Harvester plant workers were out of work for five-and-a-half months.

While the settlement proved expensive and the negotiations got precisely zero concessions from the union, the lost production didn’t turn out to be near as catastrophic as it could have been. The farm economy’s strong run turned sour in early 1980. Had the plants been at full capacity through the fall of 1979, Harvester would have been saddled with even more equipment they couldn’t sell as the dark tides of 1980 hit the farm with the worst times in modern history.

These dark days made the introduction of the new 88 Series tractors a ripple rather than a splash. The stylish, progressive machines should have lit the world on fire when they hit the market in the early 1980s. Instead, they landed with plenty of fanfare but inadequate sales simply because the market was the worst in modern history.

The farm crisis deepened into the 1980s, with a dismal market, low prices, and skyrocketing interest rates driving farmers to auction off lands and equipment, file bankruptcy, and—in extreme cases—take their own lives.

A collapsing market makes banks nervous, which means they start to reject further credit or call back lines of credit they no longer trust. Harvester was carrying a shocking $1 billion in short-term debt by April 1980, and the banks had good reason to be nervous.

They did this to IH, and the company energy from 1980 to 1982 was largely spent restructuring debt and pursuing lenders willing to float them.

On May 3, 1982, Archie McCardell was fired by Harvester. The company lost $2.4 billion from 1980 to 1983, despite selling everything that wasn’t bolted down, including their profitable division Solar Turbines Inc. and Cub Cadet (both of which live on today).

The bright light of this story is the development and good work done at Harvester in the late 1970s turned out to be precisely what was needed for red tractors to survive into the 1990s. In my opinion, Harvester’s work in the late 1970s was some of the finest done by the company and—love him or hate him—McCardell played a significant role in funneling R&D money to the engineering department.

If you’d like to read more about the last days of International Harvester, check out Red Tractors by Lee Klancher in the "related books" linked below.

Picking up the thread from the last post (Shooting History: Curveballs and Time Travel), let’s set the Wayback Machine to the mid-1970s, a few years after Brooks McCormick became the CEO at International Harvester. A descendant of the original founders and a lifetime employee of Harvester, McCormick led one of the most interesting periods in company history.

He stepped into a difficult situation at best. Harvester was saddled with immense debt, a capable if mildly staid product line, and a challenging labor environment while charging into the most difficult period in modern American history for heavy equipment manufacturers.

McCormick was a well-respected leader, despite the fact that he made a lot of unpopular changes in his efforts to turn around a lumbering giant. He ended light truck production, sold Wisconsin Steel, and—perhaps most controversially—hired Archie McCardell away from Xerox to become the Harvester CEO.

This image from the Wisconsin Historical Society shows Archie McCardell, who joined Harvester in August 1977 and soon moved up to CEO. A charismatic leader, he oversaw the most tumultuous portion of Harvester's history.

This image from the Wisconsin Historical Society shows Archie McCardell, who joined Harvester in August 1977 and soon moved up to CEO. A charismatic leader, he oversaw the most tumultuous portion of Harvester's history.McCormick spent months attempting to lure McCardell, and had to pay dearly to reel him in. Harvester gave McCardell an annual salary of $460,000, plus a $1.9 million signing bonus and a loan for $1.8 million at six percent interest. Adjusted for inflation to 2019 value, the package was worth $15.6 million, making McCardell the highest-paid CEO in America when he started in January 1978.

Paying CEOs vast sums of money is a trend that has grown exponentially since the 1970s, but its popularity has not. I personally find it hard to imagine one person being able to give that much value. Given the fact that Harvester was in shambles four years after McCardell left, there is no question that part of that blame should be laid at his feet.

McCardell was smart as a whip and, unlike previous CEOs, did not rise up through the ranks at International Harvester. I believe McCormick choose McCardell at least partially because of that. The company needed a shake-up, and a person from the outside could more easily identify and make dramatic changes.

McCardell did just that. He initiated a company-wide cost-cutting campaign, set his mind to battle the unions, and worked to get Harvester’s large departments to work together more closely and efficiently.

While today he is a popular scapegoat with historians, many of the executives who reported to him speak well of him. And the one thing he unquestionably got right—and many seem to overlook—was investing in technology.

The path he chose to put Harvester back on firm ground was to create a dazzling new array of machines. He lavished money on the engineering department, who quickly set to work designing new equipment that could allow the company to drive past its mounting debt load.

One of the harshest challenges for a heavy equipment company is research and development cycles, which require massive investment and years of engineering, design, and testing. History has consistently shown that the most successful machines come from long development cycles. The Axial Flow combine and the John Deere New Generation tractor line were both game changers, and each required a decade or more of research and development.

Harvester’s late 1970s investment in research and development would take about five years to bear fruit, which is a reasonable timeline for new machinery. Unfortunately, the timing of the release of their flagship line could not have been worse.

As part of the Pro-Ag line in 1976, the 986 had fresh styling with a nod toward operator comfort, which was marketed as a professional upgrade to the agribusinessman's office. Photo courtesy of Dwight Blok.

As part of the Pro-Ag line in 1976, the 986 had fresh styling with a nod toward operator comfort, which was marketed as a professional upgrade to the agribusinessman's office. Photo courtesy of Dwight Blok.Everything looked rosy in McCardell’s first 18 months, with a strong farm economy propelling Harvester to record sales of $8.4 billion in 1978. As the booming farm economy roared into fall 1979, McCardell’s determination to break the back of the union would prove part of his undoing.

The times were difficult for all heavy equipment manufacturers, and organized labor was one of the key challenges. Harvester had historically been more labor-friendly than others, but McCardell decided the time was right for a hard-headed approach. His poor choices and tough stance led the International Harvester plants to strike in the fall of 1979, choking production to a near standstill. More than 35,000 Harvester plant workers were out of work for five-and-a-half months.

While the settlement proved expensive and the negotiations got precisely zero concessions from the union, the lost production didn’t turn out to be near as catastrophic as it could have been. The farm economy’s strong run turned sour in early 1980. Had the plants been at full capacity through the fall of 1979, Harvester would have been saddled with even more equipment they couldn’t sell as the dark tides of 1980 hit the farm with the worst times in modern history.

These dark days made the introduction of the new 88 Series tractors a ripple rather than a splash. The stylish, progressive machines should have lit the world on fire when they hit the market in the early 1980s. Instead, they landed with plenty of fanfare but inadequate sales simply because the market was the worst in modern history.

The farm crisis deepened into the 1980s, with a dismal market, low prices, and skyrocketing interest rates driving farmers to auction off lands and equipment, file bankruptcy, and—in extreme cases—take their own lives.

A collapsing market makes banks nervous, which means they start to reject further credit or call back lines of credit they no longer trust. Harvester was carrying a shocking $1 billion in short-term debt by April 1980, and the banks had good reason to be nervous.

They did this to IH, and the company energy from 1980 to 1982 was largely spent restructuring debt and pursuing lenders willing to float them.

On May 3, 1982, Archie McCardell was fired by Harvester. The company lost $2.4 billion from 1980 to 1983, despite selling everything that wasn’t bolted down, including their profitable division Solar Turbines Inc. and Cub Cadet (both of which live on today).

The bright light of this story is the development and good work done at Harvester in the late 1970s turned out to be precisely what was needed for red tractors to survive into the 1990s. In my opinion, Harvester’s work in the late 1970s was some of the finest done by the company and—love him or hate him—McCardell played a significant role in funneling R&D money to the engineering department.

If you’d like to read more about the last days of International Harvester, check out Red Tractors by Lee Klancher in the "related books" linked below.