Obsessions Die Hard: The Myth and the Curse

This excerpt is from Obsessions Die Hard: A Motorcycle Adventure Across the Pan-American Highway's Darién Gap by Ed Culberson. Here he describes his encounter with another adventurer and his role in perpetuating the myth that this region was impassable for outsiders.

All royalties from the sale of Obsessions Die Hard will be donated to ALS of Texas.

“Contemporary man has rationalized myths, but has not been able to destroy them.”

—Octavio Paz, The Labyrinth of Solitude

“Whaddya mean there ain’t no road?” protested the scruffy, bearded man on the mud-encrusted, endure-style motorcycle with a barely legible California license plate.

The biker had pulled up beside me to ask directions as I was getting ready to mount my motorcycle at Stevens Circle in Balboa, on the Pacific side of the Panama Canal. It was 1974 and he had just arrived from the United States.

From the looks of both bike and rider, he had taken a severe beating on the four-thousand-mile ride down to the Canal Zone.

“But dammit, the map shows a road running all the way from here to Colombia!”

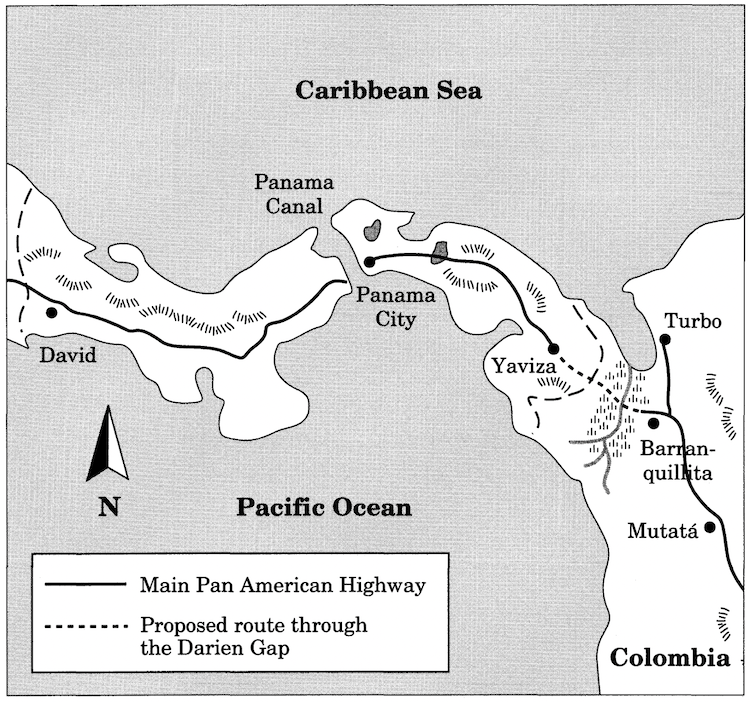

He thrust a tattered oil company map at me and pointed indignantly to the dashed line of the Pan-American Highway running east from Panama City before curving southward to the Colombian border and beyond.

“You’re right,” I conceded, “but that’s the proposed route. As of now, the road ends about fifty miles from here. Beyond the Chagres and Bayano rivers there’s nothing but the jungles and swamps of the Darién region. It would take a small army to get you and your motorcycle through the next 150 miles.”

You poor bastard, I mused. Here you’ve busted your tail riding all the way down through Mexico, Central America, and half of Panama, only to bump up against a roadblock you didn’t even know existed.

“So how in hell do I get to South America?”

“Well, you could put your bike on board a ship over there at Pier 18,” I said, pointing to the Panama Canal Balboa harbor only a block away. “Or you can fly it out to Colombia on a cargo aircraft from Tocumen Airport on the other side of Panama City. Either way, it will take time and cost you a bundle of money.”

Although I didn’t realize it, my advice was helping to perpetuate a myth, a centuries-old belief that it was simply not possible for outsiders, no matter how intrepid, to venture through eastern Panama’s Darién region and the area surrounding the Atrato River in Colombia.

I knew little then of the myth, but it didn’t matter. The battered biker didn’t look like he needed any more bad news. Thoroughly discouraged, he muttered a word of thanks, kick-started his bike to a sputtering rumble and slowly rode off around the circle.

I never saw the Californian again and do not know if he ever pressed on to the south. But that same scene, with minor variations in vehicles, characters and dialogue, has been replayed many times over the years.

Scores of unknowing travelers—motorists, motorcycle riders, bicyclists, and backpackers—have journeyed south to Panama or north to Colombia expecting the Pan-American Highway to give them an open passage across the border between the two countries. But they have been disheartened to find that along the narrow isthmus there is still a break in the highway that is supposed to extend all the way between Alaska and Argentina. That obstruction, known as the Darién Gap—in Spanish el Tapón del Darién, The Stopper—has sustained its myth by proving to be a nearly impassable barrier for wayfarers.

Today, adventuresome travelers can head east from Panama City by bumping along the 180 miles of mostly unpaved road that has been slowly and crudely extended into the previously isolated Darién region. But at the decrepit village of Yaviza the road runs out. The rutted dirt track stops at the banks of the Chucunaque River and does not begin again until the far side of the Atrato River in Colombia, a gap of less than 100 miles. When it does pick up again, portions of the route to Bogotá are often blocked by flooding, landslides, and massive rebuilding projects.

The gap in the Pan-American Highway isn’t much in terms of the sixteen-thousand-mile-long main route, which runs through eighteen countries and spans over one-half the circumference of the earth. And there is still another thirty-thousand miles of alternate and secondary roads that are also part of the overall Pan-American Highway System.

Most travelers between the northern and southern hemispheres usually bridge the Darién Gap by flying over it or boating around it. But for hard-core wayfarers intent on covering the entire primary route between Alaska and Argentina by land, that short, obscure stretch where there is no road of any kind is a frustrating obstacle, as the California biker discovered.

A decade after our brief encounter in Balboa, I would challenge that barrier. I wanted to ride my motorcycle the full length of the main Pan-American Highway between Fairbanks and Buenos Aires. My goal was to cover every mile of the established road and somehow make my way through the proposed route in the Darién. Nobody, as far as I could determine, had ever taken a motorcycle through the gap by that route. I thought of it as the Mount Everest of motorcycling.

Click to continue the adventure: