High Tech in Dark Times

When 1980 dawned, Harvester was expecting a bright future. The investments made into new equipment that began in the mid-1970s were beginning to hit the market. The company was reorganized, with component group heads who worked together to maximize and share resources. Harvester was one of the world’s largest equipment manufacturers, and the management team had a blend of cutting edge technology people and old guard Harvester leaders who understood the company’s deep history.

“If you fast forward to where we’re at right now, it’s a wonderful time to be in agriculture. It wasn’t so wonderful then.” said Gerry Salzman, referring to working for IH in the 1980s

Part of the new management strategy was regular meetings between all of the key people from the four divisions: agricultural equipment, truck, construction, and components. Dr. Glenn W. Kahle was a key member of the agricultural group, and recalls that McCardell led those meetings with energy and humor. “McCardell was a charming CEO, had a lot of talent, and was a pleasure to work with,” Kahle said. “He was a really likable guy, almost to a fault.”

One of the things McCardell did was make sure new products were funded. Kahle recalls talking with Bob Potter about that very topic. He and Potter had struck up a friendship, and the two spoke regularly. When either of them needed something, McCardell would almost invariably come through. Harvester’s ambitions to create a high-technology product were sky high in the early 1980s, and product development teams dreamed up some incredibly advanced concepts. From 1978 to 1981, Harvester’s investment in new technology was the highest in company history, with more $919.6 million spent in that four-year span. Gregg Montgomery collection

Harvester’s ambitions to create a high-technology product were sky high in the early 1980s, and product development teams dreamed up some incredibly advanced concepts. From 1978 to 1981, Harvester’s investment in new technology was the highest in company history, with more $919.6 million spent in that four-year span. Gregg Montgomery collection

Kahle recalls Potter saying, “I don't know where he gets it, but he’s got a money tree in his backyard and every time I need some money he just goes back and shakes it.”

McCardell’s money tree became something staff could rely on. Investment was one of the things McCardell emphasized during his time at the helm. The 1980 annual report would note that investment at Harvester was at its highest level in history and that capital expenditure for 1980 increased 77 percent over the previous year. The investment was overdue, as Harvester had lagged in investment throughout much of the past two decades. New equipment was part of the solution to Harvester’s ills and their only hope to regain market share from Deere & Company.

The company also faced some very tough challenges.

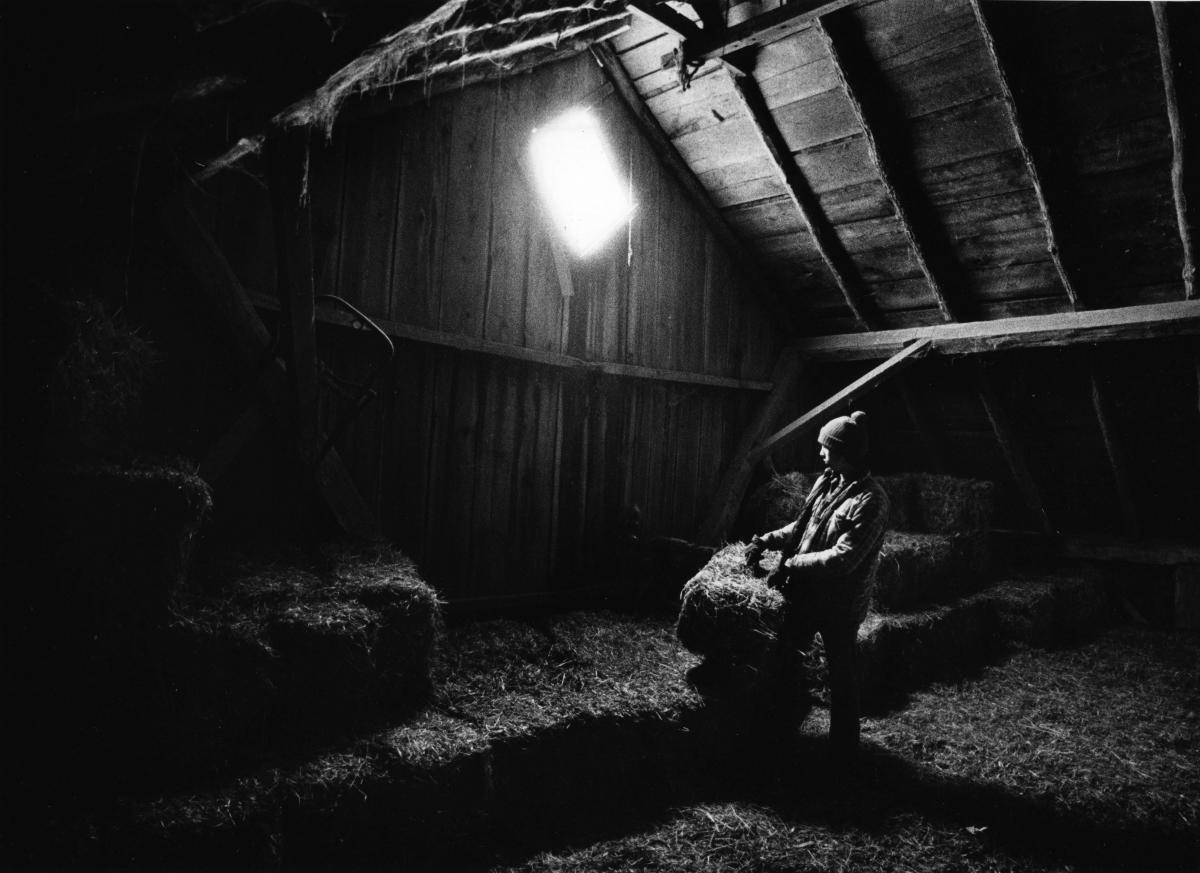

A wicked combination of factors made farm auctions rampant in the early 1980s. High interest rates, low crop prices, foreign markets that slowed or stopped, dropping land values, and high levels of debt on the average farm all conspired to make it difficult for farmers of large operations and essentially impossible for small and medium producers. The 1980s were one of the worst times in history for the farmer. Land values and crop prices dropped, debt was on the rise, and interest rates hit 20 percent. Family farmers found themselves unable to make ends meet. Wisconsin Historical Society / Gary Porter / 76307

The 1980s were one of the worst times in history for the farmer. Land values and crop prices dropped, debt was on the rise, and interest rates hit 20 percent. Family farmers found themselves unable to make ends meet. Wisconsin Historical Society / Gary Porter / 76307

Farm subsidies were inadequate, particularly for smaller operations. Farm foreclosures and bankruptcies reached the highest level since the Great Depression. These tough times were hard on anyone farming at the time, and most small and midsized producers quit or took second jobs to supplement their income.

For some, it was too much. Arthur Kirk lost his farm to the bank and took up arms in protest. He was eventually killed by a SWAT team that came out to his farm. A farmer from Minnesota killed the bankers who repossessed his land and home before taking his own life.

These two incidents were extreme examples, but the families involved weren’t the only ones who suffered tragedies because of the farm crisis. The National Farm Medicine Center reported 913 male farmers killed themselves in Wisconsin, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Montana in the 1980s. The farmer suicide rate peaked in 1982. The 1970s may have been the darkest time in American history for industry, but the 1980s were the darkest time in modern history for farmers. Harvester opened the 1980s with much of its workforce and many of its plants idling. A strike that began in November 1979 extended into April 1980 as the UAW and Harvester battled. This is the assembly line at Harvester’s West Pullman Works, circa 1980. Wisconsin Historical Society / 56753

Harvester opened the 1980s with much of its workforce and many of its plants idling. A strike that began in November 1979 extended into April 1980 as the UAW and Harvester battled. This is the assembly line at Harvester’s West Pullman Works, circa 1980. Wisconsin Historical Society / 56753

Harvester also faced very difficult challenges with labor, as the UAW and management battled tooth and nail. Archie McCardell wanted mandatory overtime, which both Deere & Company and Caterpillar had with their workforces. The UAW, which had a long history of winning these kinds of battles, pointed to a decade of record profits at Harvester. They dug in their heels and the strike that began on November 1, 1979 dragged on well into 1980. With production ground to a halt, Harvester opened the decade by losing $222 million in the first quarter of 1980.

On February 21, 1980, the Harvester annual shareholder meeting was held in Chicago. The meeting was assaulted by crowds of protesting union workers, one of whom told the New York Times that Harvester was “trying to go back to a slave shop.” Reportedly cool and collected, a smiling McCardell characterized the clash as an “investment in the future.”

The shareholders were given the pleasant news that the annual dividend payment went up despite the strike and the $222 million loss. It would be the last time McCardell personally delivered good news to Harvester shareholders.

By the end of March, McCardell had harsh news. Harvester’s credit score had been downgraded, which made its huge debt load more expensive and more difficult to finance. Envirodyne, the company that bought Wisconsin Steel, was behind on payments owed to Harvester. The strike had worsened matters for Wisconsin Steel, with their biggest customer not buying steel to build equipment. In late March 1980, Harvester repossessed the coal mines and iron ore deposits securing its loan to Envirodyne. A few days later, Wisconsin Steel padlocked the doors of its plant, told the employees not to bother coming back to work (ever), and filed for bankruptcy. Chase Manhattan Bank emptied the company’s accounts, and employee paychecks bounced. The plant’s 3,500 workers were out on the street, and Harvester would be saddled with a complicated mass of lawsuits well into the next decade.

The bankruptcy of Wisconsin Steel cost Harvester $27.7 million dollars in unplanned losses. This was a drop in the bucket compared with the hundreds of millions being lost due to the ongoing strike. The final months of strike negotiation were brutal. Both sides clung to small issues, entrenched and unwilling to give in. Finally, on April 22, 1980, the UAW and management compromised on the overtime issue and the strike was settled. It had idled 35,000 Harvester workers for five and a half months.

Industry experts predicted losses at Harvester would run in excess of $500 million for the second quarter and hit $300 million for the year. McCardell scoffed at these projections.

Farm equipment sales were already down precipitously. According to an April 27, 1980, New York Times article entitled “Farm Equipment Sales are Declining,” sales dropped industry-wide 29 percent in March 1980 alone. In the article, executives from Deere, Massey Ferguson, J. I. Case, and Allis-Chalmers all predicted continuing declines in tractor sales in the coming months. Several industry analysts quoted for the article concurred.

Stanley F. Lancaster, the general manager for North American farm equipment at Harvester, was frantically spinning the down markets and his company’s recovery from the strike as a positive. “We have a tremendous advantage going back in,” he said. “Even in March, our market share went up. We will have heavy demand in the next three quarters just to refill the pipelines.”

He was wrong. The demand was less than anticipated. McCardell was also wrong to question the analyst’s forecast for Harvester. Losses for the year for the company would total $397 million—$97 million more than the analyst predicted. The year would be the most disastrous in company history to date, during one of the most disastrous periods in history for the farmer.

In August 1980, Brooks McCormick announced his retirement would take place officially on October 31, 1980. He was one of many senior managers who left that year. One day after his departure the news hit that a team of Harvester executives agreed to forgive McCardell’s loan for $1.8 million of preferred stock as part of his bonus plan.

Paying bonuses to executives at struggling companies is fairly common today, but the move was unusual for the time. The business community reacted with dismay. “I think it’s a shame,” said Eli Lustgarten of Paine Webber.

“Harvester is in very serious financial trouble.

“They are doing the right things—investing in new plant and equipment, cutting costs and modernizing technology—but they can’t support the business they are in. They have a negative cash flow. They need to raise $500 or $600 million, and the sources are hard to find.”

Harvester’s woes were common knowledge by the end of 1980. McCardell was taking a beating in the press. “They misread the will of the workers and got almost nothing for it,” said farm business analyst Larry Hollis. “Then they misread just about everything else: the markets for trucks, construction equipment, and farm equipment.”

McCardell remained upbeat, stating that the cost-cutting measures and improved operating efficiencies would improve matters for the company. He also predicted that the new products Harvester intended to introduce in 1981 would pump up sales and profits.

Dr. Glenn W. Kahle recalls plans for a new engineering center being made about that time. Bob Potter wanted to see it happen. “Bob, it’s just a tractor company,” Kahle recalls telling him, “Plus, where are you going to get the money?” Potter assured Kahle the money tree would come through. Potter hired architects and had a six-foot-long scale model built. Potter and Kahle presented the plan to McCardell.

“Archie listened to this, and had reservations,” Kahle said. “Archie said I’ll work on it.”

In the spring 1981, Kahle recalls the new building being staked out on the grounds at Hinsdale (now Burr Ridge). That was all the further construction would progress. McCardell’s money tree was withering.

When it was producing funds, the tree had done wonderful things for Harvester. The new products were precisely what the company needed to prevail. By the end of the first quarter of 1981, it appeared that those new tractors couldn’t come soon enough. At the annual meeting in February, losses of $97 million were announced, along with the impending sale of the Cub Cadet line. The Solar Division would also be put up for sale. The sale of these profitable divisions would weaken the company overall but add desperately needed cash. McCardell and management warned that high interest costs would lead to deeper losses in the next quarter.

For the first time in 70 years, no dividends were paid to shareholders. The news was greeted with barely contained hostility, and the shareholders reportedly spent much of meeting berating management for perceived missteps and the forgiveness of McCardell’s $1.8 million loan.

Management took the beating and headed back to the office, faced with a worsening fiscal situation. Project 200 was created—management was tasked with cutting $200 million in costs. Pay was reduced 20 percent to senior management, and nonunion pay was frozen. As the year went on, more than 2,000 people were let go, entire divisions auctioned off, marginal equipment scrapped, and inventories severely cut. Project 200 netted just $100 million in savings.

As the year wore on, Harvester faced another reduction in credit rating and lawsuits from banks demanding payments and recalling loans.

The new line was introduced in the fall of 1981 with great fanfare. The new 50 series was a terrific upgrade, but most farmers weren’t in a position to buy any color of farm tractor, and sales were too thin to rescue Harvester.

McCardell led a massive $5.5 billion refinancing effort and was able to get 225 banks to sign new agreements to float the company. The Solar Division was sold for $505 million to Caterpillar, netting more cash and keeping the company alive, but a loss of $163 million in the third quarter didn’t help matters. Early 50 series prototype. Gregg Montgomery collection

Early 50 series prototype. Gregg Montgomery collection

An analyst from Merrill Lynch was not impressed by Harvester’s efforts in the 1980s, commenting, “It’s an overly optimistic approach; they’re depending on the economy to bail them out. They’ve based their decisions on the assumption that everything is going to be rosy one day. They should have figured that everything was going to be terrible and based the decisions on that.”'

Despite pushing inventory out the door with discounts as high as $7,000 on large tractors, losses continued to mount through the end of 1981. The year closed with a $393 million dollar loss. McCardell announced that plants would close for the holidays to reduce costs and extra inventory, and would remain closed into February. He also announced that he would seek another $100 million in concessions from the UAW. Harvester’s investment in technology in the late 1970s and early 1980s created a line of machines that set new standards in the industry. Wisconsin Historical Society

Harvester’s investment in technology in the late 1970s and early 1980s created a line of machines that set new standards in the industry. Wisconsin Historical Society

When it was suggested that he would have better luck negotiating with workers if he gave back the $1.8 million bonus awarded to him, he stated that he and the company were working on “unwinding” that agreement. The agreement was indeed unwound and, along with it, McCardell’s time with Harvester. After posting losses of $299 million in the first quarter of 1982, McCardell was asked to step down in May 1982. Perhaps not ironically, a new contract with the UAW was ratified the day after he left.

Louis Menks was named McCardell’s successor and took on the onerous task of trying to keep the ailing giant afloat. He succeeded for several years, but these were hard times for Harvester, as the lack of cash made creating new machines essentially impossible. The cash was so tight that a portion of the Hinsdale Farm (now known as Burr Ridge) was sold. Giving up the ground upon which the original Farmall was tested was a hard loss indicative of the dire conditions facing Harvester.

The times were hard on employees, as well. The sheer magnitude of the company made it difficult for some to grasp the situation. Ken Ryan had been an engineer in the agricultural group since 1959. “We just had a really outstanding group of people,” he said. “IH was strong in design and engineering. They were strong in their manufacturing skills. And that’s why it was so hard to picture management not being able to lead this group. How can we be losing out? We’ve got our act together, we’re building a great product, how could this thing be slipping downhill?”

Steve Warner, an engineer at Case IH today, started out as an intern at the engineering center in 1980. His experience shows that even young employees knew things weren’t going well. “In those days I was pretty naïve,” he recalled. “I didn’t pay nearly the attention that I paid [to] what’s going on with the company today. I didn’t understand it—I was just a young engineer coming into work and didn’t really give it a whole lot of thought. We had regular visits by the banks when they would do the refinancing. That was really strange to see three or four buses pull in out front of Burr Ridge and gobs of bankers get out and come through the facility, it seemed like it was every three or four months there for a while.”

Gerry Salzman worked in the sales department in the early 1980s, helping to launch new equipment. He saw his department decimated from layoffs. “That was a tough period of time, and you really said, ‘Should I stick [it] out? Shouldn’t I?’” Salzman said. “For those of us that said, ‘You know what, I think I’ll stick it out,’ that was a difficult decision. And it was tough. You put hours in, and it was stressful hours, trying to figure out how we do this and how we do that. It was tough on marriages; it was tough on relationships. And there was a lot of suggestion by family and friends to say, ‘Why are you doing this? Why don’t you do something else?’”

Many were either laid off or moved on to other jobs. In some cases, young and bright people were able to move up as the more senior (and expensive) folks took early retirement packages or were laid off.

As the 1980s progressed, the farm crisis only deepened. Efforts were made to relieve farmers, but various aid packages mostly helped larger farms more than small and medium-sized ones. Very few farmers purchased heavy equipment during this time. The farm crisis was near rock bottom in October 1983, when this photo of Kenneth Boeck harvesting corn was taken. Plummeting prices and land values resulted in an unprecedented number of bankruptcies and foreclosures.

The farm crisis was near rock bottom in October 1983, when this photo of Kenneth Boeck harvesting corn was taken. Plummeting prices and land values resulted in an unprecedented number of bankruptcies and foreclosures.

Jim Widmer / Wisconsin Historical Society / 92637

The effect on Harvester was cataclysmic, but they weren’t alone. The 1970s had left many heavy-equipment manufacturers in serious trouble. Harvester had in excess of $1 billion in debt. According to a Harvard Business School study, so did Chrysler Corporation, Massey Ferguson, Eastern Airlines, and Lockheed. Braniff, Continental, Allis-Chalmers, and White Motor Corporation also had very debt loads. Very few of these companies survived.

Lockheed stopped producing commercial jets and was saved from failing completely by a wealthy investor in the late 1980s. Braniff failed to obtain financing and abruptly ceased operations on May 12, 1982. Eastern bought some of Braniff’s routes, was sold to Texas Air in 1986, and failed entirely in 1991.

White Motor Corporation had built heavy trucks since 1898, but their truck division was sold to Volvo in 1981. The agricultural division had been sold in 1979 and ended up a part of Massey Ferguson in 1985.

Massey Ferguson was bailed out by the Canadian government in 1981 and eventually became part of the conglomerate AGCO. Allis-Chalmers stopped production of agricultural and construction equipment in 1985 and sold off their energy business. Shreds of the company also became parts of AGCO.

Chrysler was bailed out by the U.S. government, a route Harvester never tried. Management at the time would later say it was just not something they were willing to pursue.

Even John Deere wasn’t immune. The agricultural division lost money and cut staff from 68,000 in 1980 to 38,000 in 1988. At one point, the company built 11 months’ worth of inventory and was forced to offer deep discounts to move the machines. Deere reacted to the times by modernizing their plants and making careful cuts in materials, labor, and overhead so that they would be profitable even running at 50 percent capacity. They also did contract work, making axles for Winnebago and painting bumpers for Chrysler. “We’ll try to run anything we can through our plants,” said L. Neel Hall, Deere’s senior vice president.

The hard economic times of the 1980s claimed many victims. By 1983, it was clear that Harvester would be one of them. Many pieces had already been sold off and the employee ranks were decimated. Cost cutting would not be enough to keep the old giant afloat. Farm problems in the 1980s led to demonstrations and strikes to help illustrate the fact that the changing economy didn’t work for family farms. Family farmers either had to take jobs off the farm or sell out and move on. This young man is at a demonstration on January 28, 1985. Gary Porter / Wisconsin Historical Society / 9267

Farm problems in the 1980s led to demonstrations and strikes to help illustrate the fact that the changing economy didn’t work for family farms. Family farmers either had to take jobs off the farm or sell out and move on. This young man is at a demonstration on January 28, 1985. Gary Porter / Wisconsin Historical Society / 9267

Donald D. Lennox, Harvester’s CEO, told the New York Times, “There’s going to have to be some marriages, or there’s going to have to be some deaths.”' A merger or a flat-out closing of some Harvester divisions were needed for the company to survive. The agricultural division was put up for sale. This was a very deep cut. Whatever happened after the sale, Harvester would be a very different company.

In 1983, talks began between Tenneco, a diversified Houston-based company with J. I. Case in its portfolio, and Harvester, but they fell apart over the issue of unfunded pensions at Harvester. Discussions resumed and in November 1984 Harvester agreed to sell the agricultural division. Harvester would retain the truck division, but agreed to do so under a new name and would eventually adopt the name Navistar.

The agricultural division would be blended with Case Corporation, giving both companies a chance to not only survive hard times but acquire a stronger market share.

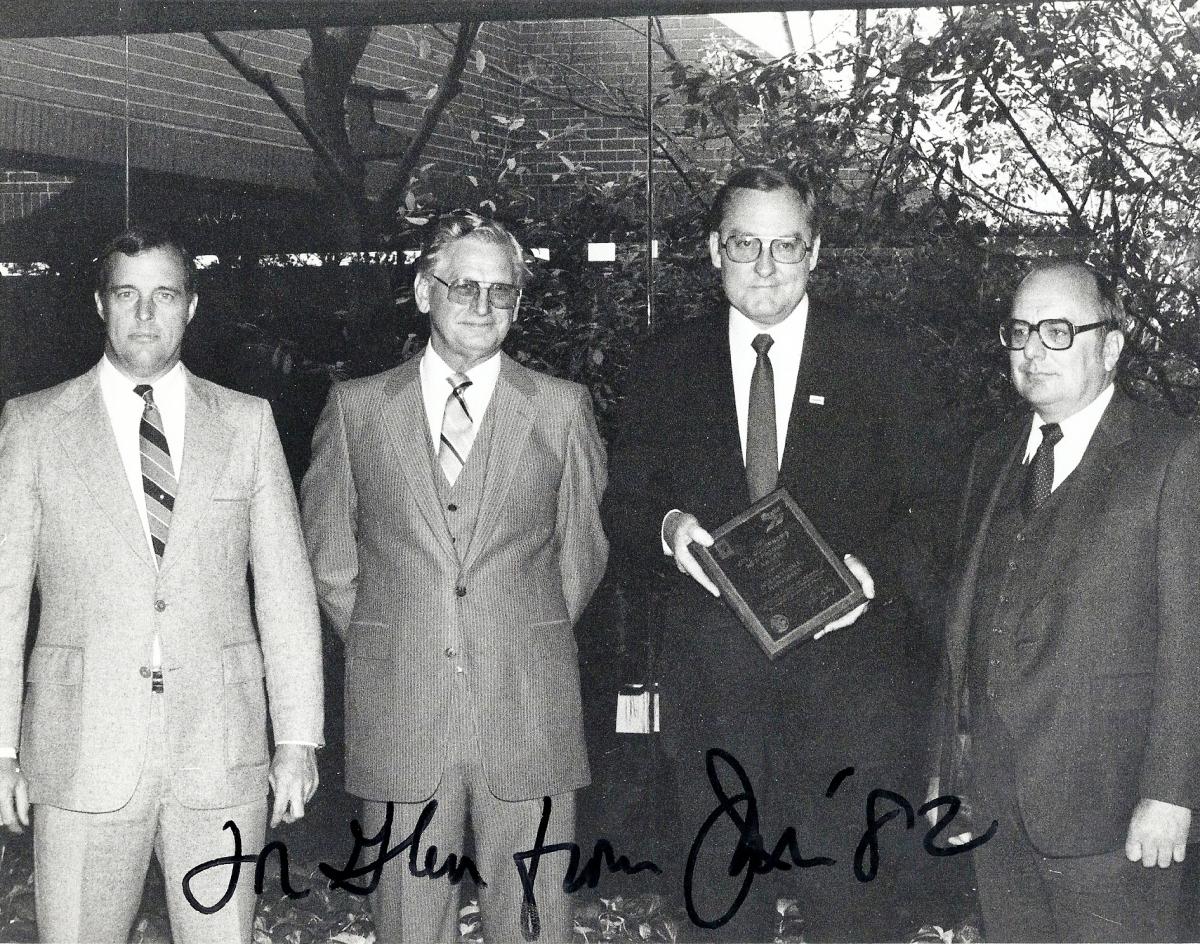

Larry D. Hollis, a widely quoted agricultural business analyst applauded the merger, saying, “You’d havea much more formidable competitor with Deere.” Illinois Governor James R. Thompson presented the Illinois Society of Professional Engineers' Governor's New Product Award for the 50 Series tractor to the Harvester engineering team in 1982. From right to left: Glenn W. Kahle, Gov. James R. Thompson, Rock Island Farmall plant manager Matt Glowgowski, and Matt’s assistant, Arnt. Glenn W. Kahle collection

Illinois Governor James R. Thompson presented the Illinois Society of Professional Engineers' Governor's New Product Award for the 50 Series tractor to the Harvester engineering team in 1982. From right to left: Glenn W. Kahle, Gov. James R. Thompson, Rock Island Farmall plant manager Matt Glowgowski, and Matt’s assistant, Arnt. Glenn W. Kahle collection

Even people at Deere & Company saw the wisdom in the merger. Jim Walker was working to develop the dealer network at Deere in 1985. “When I was on territory with John Deere, my biggest competitor was International Harvester,” Walker said. “When they merged and then picked up the Case end of it, we thought, ‘Okay, that’s a strengthening, that’s naturally a strengthening.’ You already knew your IH counterpart was formidable, that they were an innovator because of Axial-Flow combines, things that they were trying to do to be unique and first in class. And we thought that was a strengthening of that brand, bringing them together . . . it was very strategic.”

For the people who worked with or for Harvester, the move was very difficult. Steve Warner, a young engineer at the time, recalls how hard the buyout was on the staff. “That was an emotional time for all of us. I have a picture of my last International Harvester paycheck,” he said.

To find out the rest of the incredible story of International Harvester, get your copy of Red Tractors 1958-2013 here!

Previous Excerpt - Next Excerpt