Subterfuge

To celebrate the 2016 Indy 500, Octane Press is releasing excerpts from Jade Gurss' incredible award-winning book Beast: The Top Secret Ilmor Penske Engine That Shocked The Racing World At The Indy 500, which tells the true story of the astonishing events that led up to the infamous 1994 Indy 500, all from the perspective of the men involved.

BEAST: CHAPTER EIGHT

It's A Pontiac

“A lie gets halfway around the world before the truth has a chance to get its pants on.”

— Winston Churchill

What to name the new engine to avoid drawing attention?

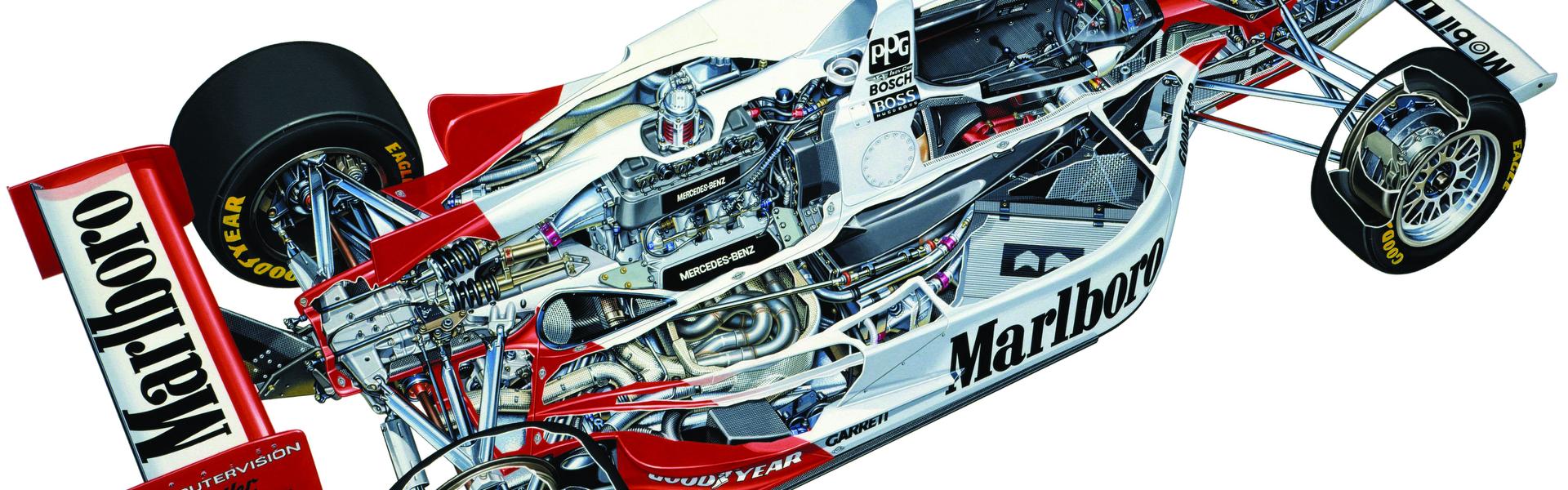

At Ilmor, each technical drawing had a section in its lower righthand corner where the part and project name were identified. Ilmor had just completed the design of their 1994 CART engine, which was named the 265D (“265” for 2.65 liters, and “D” to indicate the fourth iteration of the engine), so it made sense that the next project would be named 265E. This choice was a diversion—the engine would be 3.43 liters. Internally, it was just called “the E.” Many suggested E was for “evenings,” due to the workload. (It could also have stood for “every evening.”)

As the design progressed and the time came to manufacture parts, Ilmor faced the dilemma of exposing the drawings to a handful of suppliers. While in-house capabilities included large, robotic CNC machines to make many of the parts, some parts could not be made there. The same suppliers did extensive work for nearly all the Formula 1 teams and competitor Cosworth, all of which were located in a small area around Northamptonshire, thus increasing the likelihood the engine could be exposed.

Which suppliers could be trusted? They had to be judged both by their integrity not to divulge details and by their ability to produce quality parts in an extremely short time. Even minor errors could cripple the project.

Zeus Castings had forged the engine blocks and critical parts on every Ilmor engine, going so far as to build separate areas inside their facility to make certain each project was handled in secrecy. But their relationship with Ilmor went much deeper.

“When Ilmor completed their first engine, the 265A, Zeus cast the engine blocks,” said Alan Cook. “So Paul and Mario drove to Zeus with one of those blocks filled with a bottle of champagne in each cylinder. Then they went into the pattern shop and had champagne for people who had worked on the plenum [the air box on top of the engine that also held the fuel injectors]. As long as I was going to Zeus, ten to twelve years later, they still had the corks hanging somewhere and they still talked about it. The motivation that gave Zeus, and the goodwill towards Ilmor, with just a relatively simple act, was unmeasurable. So when we’d go to Zeus and say, ‘We’re going to do this engine, and we’ll want everything very quickly,’ they would bend over backwards to do it because Paul and Mario had built a relationship with them. It was very important.”

“The local suppliers to Ilmor, it was a very tight family because they were as big of a part at Ilmor as people who worked there,” said le Roux. “A lot of them were small businesses. For example, Brian Smith, who owned Delta Engineering. It was only him and Clive Gant, and the two of them made fantastic parts. In hindsight, the engines weren’t that expensive because we had this network of very small suppliers where the guy who owns the company is working the machines. It was their personal interest, probably more fans of the racing than even the people working at Ilmor.”

When possible, outside vendors were left out entirely, which was a boon for fourteen-year-old Patrick Morgan. Because the E’s pistons were much larger than usual, Patrick was assigned to machine the raw piston billets prior to forging rather than risk having a vendor do the same. The raw material was RR58, a metal devised by Rolls-Royce to make pistons for the Merlin engine used in the P-51 Mustang. The material hadn’t been improved on in the decades since.

Over his Christmas break from school, Patrick was in the machine shop of the Morgans’ home morning until night, turning out the pistons for ten pence each. He completed 550 pistons in three days, earning a cool fifty-five pounds. Not bad!

David Wilford, who was in charge of procuring the development parts for Ilmor, worked directly with many of the suppliers. Just as some of Ilmor’s designers still used pencil and paper, Wilford managed all the pushrod parts, purchase orders, and inventory in what was known as “the red book,” which was painstakingly organized in multiple columns with a pen and a highlighter. It was the manual equivalent of a spreadsheet database.

“One of the things that really helped with [suppliers] was that Ilmor was fantastic about paying its bills,” said Wilford. “We always paid on the dot. That’s always a big help. And we used to have use of T-shirts and caps and goodies. So we often delivered a purchase order with a lot of work that meant someone’s got to work the weekend, but along with that would be a goodie bag. We’d just gone through a recession, and so, from a supplier’s standpoint, it was painful working late, but you knew you were going to get paid. We expected people to deliver but we were nice people to deal with.”

Sometimes vendor relations required some additional influence.

Alan Cook, in creating the gear train, designed a toothed-belt to drive the pumps on both sides of the engine. Because the engine was unique, the belt was not a standard item.

“These belts come in standard numbers of teeth,” Cook explained. “There might be an eighty-tooth and a ninety-tooth, but there wouldn’t be an eighty-three-tooth belt. And we wanted a nonstandard belt. The purchasing department was having trouble with the supplier. Their timeframe was completely unacceptable, and it meant we couldn’t run the engine when we wanted to.

“We presented this problem to Paul. He was very persuasive, wasn’t he?” Cook laughed. “So, he called the supplier and said, ‘Hello, I’m Paul Morgan and I’d like to speak with your director. Yes, I’d like an eighty-three-tooth belt. I understand that’s going to be a problem and a long lead time.’ The director said it would be twenty weeks or whatever. So Paul asked ‘Why is that?’ ‘Because it takes us so many weeks to make the die.’ So Paul said, ‘Well, we will make the die for you. Now, how long will it take?’ and so on until at the end they agreed to do it in four weeks without our help whatsoever! Paul just took charge of the situation and very nicely got them to agree to something that, ten minutes before, was called impossible.”

For some parts, a phone call wouldn’t do. Compared to the valves in a four-per-cylinder engine, the E’s valves, at two per cylinder, were much bigger and instantly recognizable as something different.

Del West, located in California, was the valve supplier to nearly all major engine builders, and was in close contact with many of the companies Ilmor was striving to beat. This could be a major problem, so a simple ruse was concocted, and Penske’s NASCAR race team provided the perfect cover. To hide their actual purpose, the valve drawings were labeled “Pontiac.” The camshaft drawings also received a name change.

“I drew up the valves and we were going to send it to Del West,” said le Roux. “So we said, ‘We need these valves for Roger’s NASCAR engine.’ That was our cover because NASCAR valves are much bigger than what we had been using. And they swallowed that hook, line, and sinker.”

Taking another risk, one of the design team even called Mike Devin at USAC to confirm several items in the rulebook.

“I had a sneaking hunch that Ilmor was going to do something,” said Devin. “I didn’t know what they were going to do. I had no idea. From my position, when an intelligent man asks intelligent questions, he does it for a reason. They just wouldn’t ask, ‘How about this? Whaddaya think of this?’ I’d never had a chit-chat with Ilmor. But I had no sense of whether they were building cylinder heads for General Motors or a block for [team owner John] Menard. I didn’t know where this was going, but I had a hunch it was something.”

Did any of the vendors come close to figuring it out?

“No. I don’t think they did,” answered Wilford. “People would ask, because obviously some of the bits were very different. . . . It would have been difficult for one person to figure out. And when people asked about the 265E, we would just brush it off as ‘Oh, it’s just an engine project that we’re working on. We’re expanding the scope of the business and getting involved in road car projects and. . .’ People were respectful of confidentiality.”

For the full story, check out Beast here, and learn how the intrigue, engineering, and utter audacity of two men turned the racing world upside down.

Previous Chapter-Next Chapter