Old Blankets and Rusty Iron

This article was originally published as a feature in the Ageless Iron section of Successful Farming magazine, where Lee Klancher is a regular contributor.

I was sitting in my favorite living room chair a few nights ago, taking in a late evening coffee and the glow of candles in our fireplace while tamping out the last of the day’s fires on my laptop. A bit of the bone-chilling cold enveloping the Midwest had crept down to Texas and under the door into our living room, and I warmed myself with an old knit blanket zig-zagged with stripes of green, black, yellow, and red.

Made by my grandmother, the blanket is nearly as old as I am. It resided on her green couch for as long as I can remember until I graduated from college, when the green couch came to my house and the zigzag blanket tagged along. The couch was retired circa 2008, but the blanket remained a fixture in my living room. Unfrayed and still tightly knit, the blanket’s endurance gives testament to my grandmother’s careful Slovenian craftsmanship.

That evening and many like it, the old blanket transported me four decades back to my grandparents’ living room in their home near Willard, Wisconsin, a place of comfort and respite during my childhood as well as my adult life. The blanket evokes boisterous card games in a crowded kitchen, the smell of apples and cinnamon generated by Slovenian strudel, and the crunch of fall leaves on my favorite deer hunting drive on North Mound, the hill behind the house.

The evocative power of objects is something I know a bit about, as I have spent much of my professional life studying, writing about, and photographing old machines, particularly tractors, which are time machines on a personal level for so many of us and, on occasion, a window into the evolution of farm technology.

A particularly remarkable encounter with those timeless pieces came just a few months ago, during a trip making photographs with tractor collector Bruce Keller in Central Wisconsin.

Bruce has one of the world’s largest and most interesting collections of John Deere tractors. He’s a hard worker with a wry sense of humor, not to mention a deep understanding of and appreciation for history, and I enjoy working with him very much.

Many of his tractors are like grandma’s zigzag blanket, except instead of just being significant to a nerdy Sconnie boy such as myself, these objects evoke turning points in agricultural history.

A 1984 Model 301A Turf Tractor in a striking teal color, courtesy of the Bruce Keller Collection.

A 1984 Model 301A Turf Tractor in a striking teal color, courtesy of the Bruce Keller Collection.

While waiting for the light to warm up for a shot on a blustery October day, I asked Bruce which of the machines were his favorite. The question appeared to startle Bruce, and as he thought it through, a mischievous light brightened his countenance.

“Just one?” he said. “That’s something I’d have to think about.”

He eventually settled on a handful of machines, most of them appealing to him due to their significance (though one was because his late wife loved the unique teal color). Near the top of Bruce’s list is an early GP prototype that rests in the office of his museum. The GP is arguably the most interesting single Deere model, as it represents so many turning points in agricultural history.

The John Deere GP was a response to the Farmall Regular, which was the first general purpose tractor. The tricycle design was an innovation, allowing the machine to not only plow and turn a belt, but also cultivate crops. The machines were selling like mad in the late 1920s and early 1930s, and the entire industry scrambled to release competitive machines.

Deere’s core philosophy is to develop new models with great care and consideration—for the Model D and the New Generation, for example, Deere invested more than a decade of development.

In the case of the GP, Deere’s haste to enter the market caused them to depart from tradition and release the model with minimal testing and development. The result was a heavily flawed machine. During the GP’s production span, Deere was constantly improving the model, making the GP line include dozens of production changes.

One can look at the decades of well thought-out development that took place after the GP, and conclude that the flawed machine convinced Deere management to stay true to their core values going forward.

The production model of the Model C was dubbed the GP. This is an extremely rare model, the first Model GP built. It is serial number 200211.

The production model of the Model C was dubbed the GP. This is an extremely rare model, the first Model GP built. It is serial number 200211.

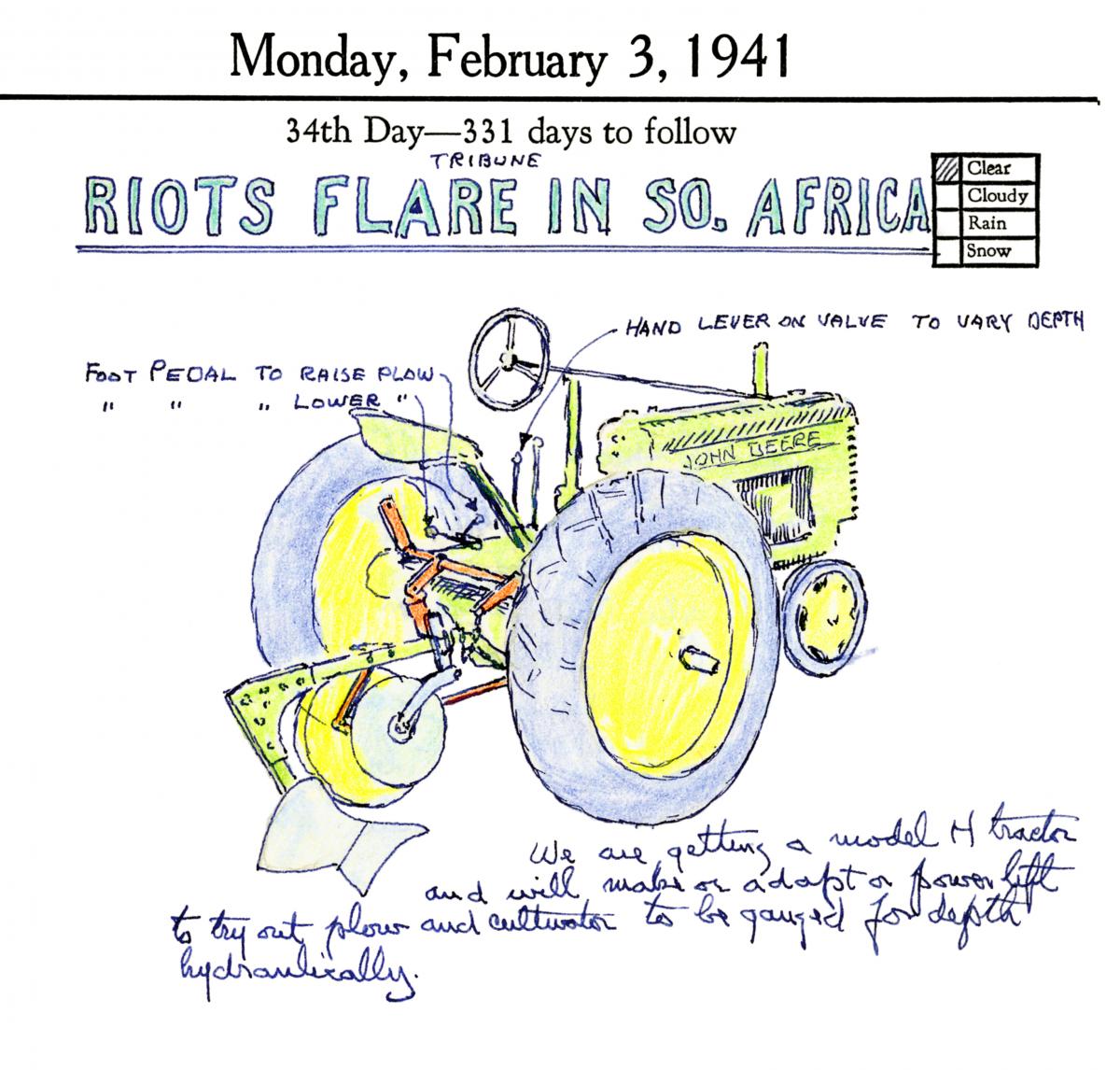

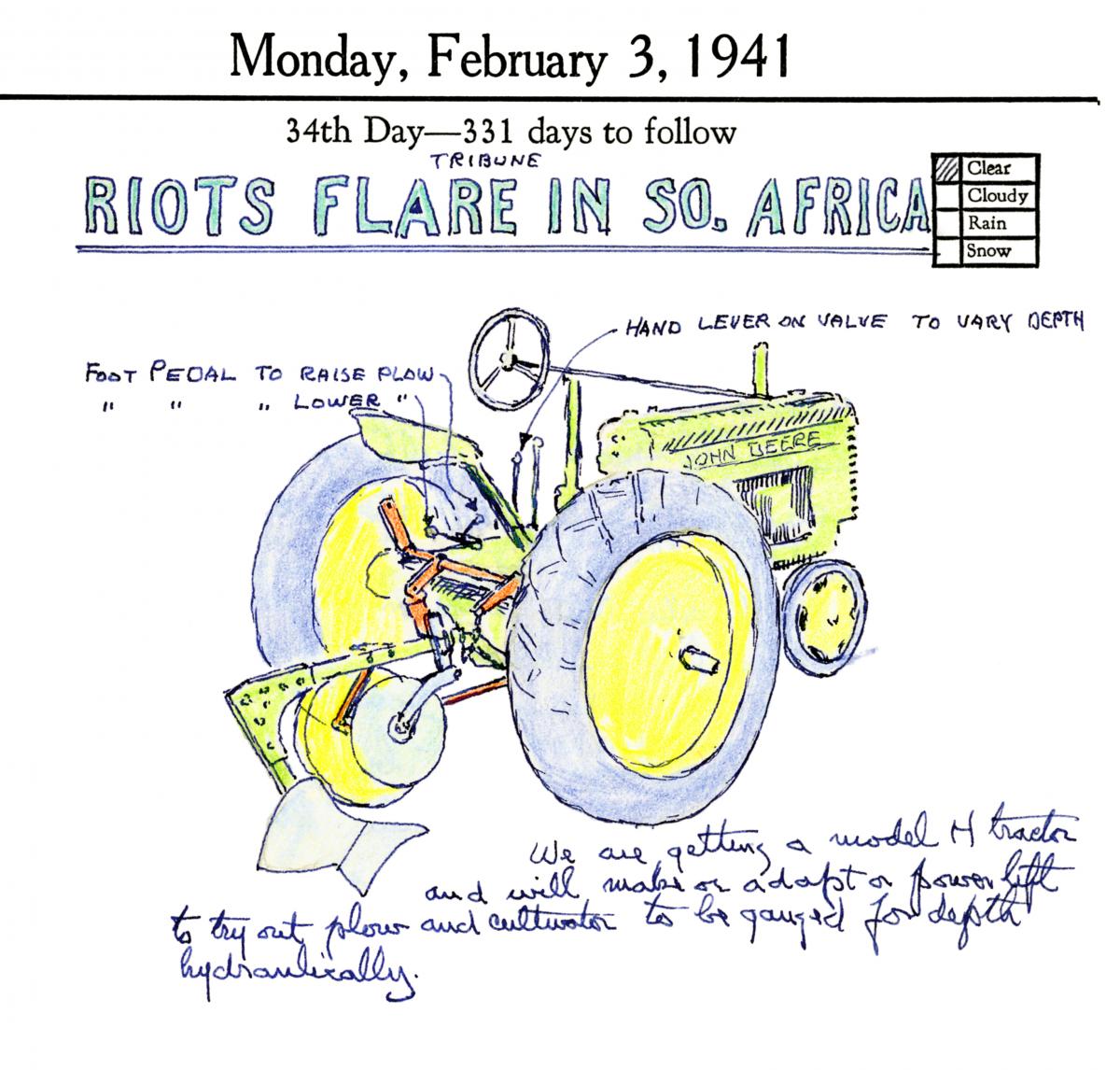

The GP is made perhaps more intriguing by the fact that one of the innovative minds behind the machine, Theo Brown, scrupulously maintained a daily diary chronicling his life and, as part of that, the ideas, sketches, and new developments that created the GP.

Just as the GP is preserved in Bruce’s collection, Theo Brown’s diary is housed by the Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI). Not long before visiting the GP with Bruce, I spent several days in the WPI archive perusing the original copies of Theo Brown’s diary. The diary is a beautiful object, with gorgeous leather covers embossed with the year. Holding this important piece of history is a humbling experience.

Paging through the diary, Brown’s daily life unfolds in scrapbook fashion, with his detailed recording of notable events of the day accompanied by pasted-in snapshots and beautiful sketches that range from gardens and homes to ideas for new implements and machines.

Brown was a prolific inventor, and the sketches and ideas in his diary underscore the impact of his dozens of patents. His talents were broad, and the brilliant engineer was also a talented photographer, writer, inventor, and artist. The diary’s impact is strengthened by the fact he was clearly a man of character, dedicated to his family, community, and industry.

Seeing the man’s daily life unfold from father and innovator to grandfather and patriarch of the Deere company and, for that matter, the agricultural engineering community was a powerful experience. The diary’s intimate detail is a window into a time when machines transformed our society, and I believe the diary is one of the most important artifacts of agricultural history.

Theo Brown Diary entry dated to February 3rd, 1941. Photo courtesy of the archives at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

Theo Brown Diary entry dated to February 3rd, 1941. Photo courtesy of the archives at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

Just as grandma’s blanket is a physical tie to a world that was pivotal to my development, Theo Brown’s diary and Bruce’s GP are pieces that provide insight into the societal transformations that have built the culture in which we presently reside.

Such objects provide context and meaning to our lives by connecting our present to our past. They are important, whether for future historians to understand how and why we arrived at today, or simply as a personal keepsake that reminds you of important people long gone while keeping your legs toasty on a cool winter day.

If you’d like to read more about John Deere History, check out the “related books” linked below.

I was sitting in my favorite living room chair a few nights ago, taking in a late evening coffee and the glow of candles in our fireplace while tamping out the last of the day’s fires on my laptop. A bit of the bone-chilling cold enveloping the Midwest had crept down to Texas and under the door into our living room, and I warmed myself with an old knit blanket zig-zagged with stripes of green, black, yellow, and red.

Made by my grandmother, the blanket is nearly as old as I am. It resided on her green couch for as long as I can remember until I graduated from college, when the green couch came to my house and the zigzag blanket tagged along. The couch was retired circa 2008, but the blanket remained a fixture in my living room. Unfrayed and still tightly knit, the blanket’s endurance gives testament to my grandmother’s careful Slovenian craftsmanship.

That evening and many like it, the old blanket transported me four decades back to my grandparents’ living room in their home near Willard, Wisconsin, a place of comfort and respite during my childhood as well as my adult life. The blanket evokes boisterous card games in a crowded kitchen, the smell of apples and cinnamon generated by Slovenian strudel, and the crunch of fall leaves on my favorite deer hunting drive on North Mound, the hill behind the house.

The evocative power of objects is something I know a bit about, as I have spent much of my professional life studying, writing about, and photographing old machines, particularly tractors, which are time machines on a personal level for so many of us and, on occasion, a window into the evolution of farm technology.

A particularly remarkable encounter with those timeless pieces came just a few months ago, during a trip making photographs with tractor collector Bruce Keller in Central Wisconsin.

Bruce has one of the world’s largest and most interesting collections of John Deere tractors. He’s a hard worker with a wry sense of humor, not to mention a deep understanding of and appreciation for history, and I enjoy working with him very much.

Many of his tractors are like grandma’s zigzag blanket, except instead of just being significant to a nerdy Sconnie boy such as myself, these objects evoke turning points in agricultural history.

A 1984 Model 301A Turf Tractor in a striking teal color, courtesy of the Bruce Keller Collection.

A 1984 Model 301A Turf Tractor in a striking teal color, courtesy of the Bruce Keller Collection.While waiting for the light to warm up for a shot on a blustery October day, I asked Bruce which of the machines were his favorite. The question appeared to startle Bruce, and as he thought it through, a mischievous light brightened his countenance.

“Just one?” he said. “That’s something I’d have to think about.”

He eventually settled on a handful of machines, most of them appealing to him due to their significance (though one was because his late wife loved the unique teal color). Near the top of Bruce’s list is an early GP prototype that rests in the office of his museum. The GP is arguably the most interesting single Deere model, as it represents so many turning points in agricultural history.

The John Deere GP was a response to the Farmall Regular, which was the first general purpose tractor. The tricycle design was an innovation, allowing the machine to not only plow and turn a belt, but also cultivate crops. The machines were selling like mad in the late 1920s and early 1930s, and the entire industry scrambled to release competitive machines.

Deere’s core philosophy is to develop new models with great care and consideration—for the Model D and the New Generation, for example, Deere invested more than a decade of development.

In the case of the GP, Deere’s haste to enter the market caused them to depart from tradition and release the model with minimal testing and development. The result was a heavily flawed machine. During the GP’s production span, Deere was constantly improving the model, making the GP line include dozens of production changes.

One can look at the decades of well thought-out development that took place after the GP, and conclude that the flawed machine convinced Deere management to stay true to their core values going forward.

The production model of the Model C was dubbed the GP. This is an extremely rare model, the first Model GP built. It is serial number 200211.

The production model of the Model C was dubbed the GP. This is an extremely rare model, the first Model GP built. It is serial number 200211.The GP is made perhaps more intriguing by the fact that one of the innovative minds behind the machine, Theo Brown, scrupulously maintained a daily diary chronicling his life and, as part of that, the ideas, sketches, and new developments that created the GP.

Just as the GP is preserved in Bruce’s collection, Theo Brown’s diary is housed by the Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI). Not long before visiting the GP with Bruce, I spent several days in the WPI archive perusing the original copies of Theo Brown’s diary. The diary is a beautiful object, with gorgeous leather covers embossed with the year. Holding this important piece of history is a humbling experience.

Paging through the diary, Brown’s daily life unfolds in scrapbook fashion, with his detailed recording of notable events of the day accompanied by pasted-in snapshots and beautiful sketches that range from gardens and homes to ideas for new implements and machines.

Brown was a prolific inventor, and the sketches and ideas in his diary underscore the impact of his dozens of patents. His talents were broad, and the brilliant engineer was also a talented photographer, writer, inventor, and artist. The diary’s impact is strengthened by the fact he was clearly a man of character, dedicated to his family, community, and industry.

Seeing the man’s daily life unfold from father and innovator to grandfather and patriarch of the Deere company and, for that matter, the agricultural engineering community was a powerful experience. The diary’s intimate detail is a window into a time when machines transformed our society, and I believe the diary is one of the most important artifacts of agricultural history.

Theo Brown Diary entry dated to February 3rd, 1941. Photo courtesy of the archives at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

Theo Brown Diary entry dated to February 3rd, 1941. Photo courtesy of the archives at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Just as grandma’s blanket is a physical tie to a world that was pivotal to my development, Theo Brown’s diary and Bruce’s GP are pieces that provide insight into the societal transformations that have built the culture in which we presently reside.

Such objects provide context and meaning to our lives by connecting our present to our past. They are important, whether for future historians to understand how and why we arrived at today, or simply as a personal keepsake that reminds you of important people long gone while keeping your legs toasty on a cool winter day.

If you’d like to read more about John Deere History, check out the “related books” linked below.