Beast Three: The Decision

Chapter 3 from Beast by Jade Gurss

To celebrate the release of the revised, second edition, Octane Press is releasing excerpts from the award-winning book Beast: The Top Secret Ilmor Penske Engine that Shocked the Racing World at the Indy 500.

Join our mailing list for specials on the second edition and learn how the intrigue, engineering, and utter audacity of three men turned the racing world upside down. Limited quantities of first edition available.

BEAST: CHAPTER THREE

Nothing Is Impossible

“The word invent, it’s inapt. There’s not one moment where you flip the switch and it starts running. It’s a gradual coalescence of different things, a confluence of energies.”

— Michael Nesmith

Musician, songwriter, filmmaker, and novelist, responding to claims he “invented” MTV (I Want My MTV: The Uncensored Story of the Music Video Revolution)

“I’ll have the rattlesnake,” Mario Illien told the waiter at the luxurious Wigwam Resort in Phoenix, Arizona, in June 1993.

Sitting next to Illien (and his grilled reptile) was fellow engineer Paul Morgan. The two had formed the racing-engine design and manufacturing company Ilmor Engineering Ltd. in November 1983. It wasn’t unusual to find the pair enjoying meals around the globe as a result of their business designing engines for Indy car and Formula 1 race teams. Illien even had an ongoing game of one-upmanship with one of their corporate backers to see who could ring up the largest dinner tab. (Illien won that challenge with an epic postseason meal to celebrate another championship for the Ilmor team.) One of Ilmor’s tenets was never to taunt the racing gods by failing to celebrate your successes properly.

This evening’s meal was more businesslike. They were joined by their third partner, American business magnate and racing legend Roger Penske. Penske had financed Ilmor’s creation a decade before and held a twenty-five percent stake in the company. Less than three weeks before, Penske and Ilmor had won the 1993 Indianapolis 500, and now they were together to discuss plans for next year’s race, slightly more than eleven months away.

It was Penske’s record ninth Indy 500 win as a team owner and his fourth win in the past seven years. His team had also won ten Indy pole positions (the top qualifying position, most likely named because early-twentieth-century American races took place on horse racing tracks, where the fastest horse was placed in the inside starting gate, closest to the poles marking the race distance) and eight Indy car season championships since 1977. His legacy was cemented, but the moment the checkered flag fell on the 1993 race, he began thinking about what it would take to win his tenth.

Morgan and Illien had been deep in thought about the same thing. Their small British company had designed and manufactured the winning engine for the past six races at Indy, including three victories with Team Penske. They were confident that several years of seemingly small changes in engine rules for the 500, set by the United States Auto Club (USAC), the race’s sanctioning body, presented an opportunity to build a new engine that could give them what Penske always called “the unfair advantage.”

By 1993, Penske was the most successful open-wheel race team owner in American history and one of the top business executives in the world as CEO of Detroit Diesel and chairman and CEO of Penske Truck Leasing. His Penske Retail Automotive Group owned auto dealerships featuring most of the major automobile and truck brands. Several of these dealerships were among the largest and most successful in the world. Collectively, they were selling nearly 40,000 vehicles per month.

Born in New Jersey and raised in the Cleveland suburb of Shaker Heights, Ohio, Penske’s love of racing was fueled by a memorable trek with his father to the 1951 Indianapolis 500. He became a superb race-car driver while at Lehigh University. After graduating with a degree in business administration, his fortunes behind the wheel grew. He was selected “1961 Driver of the Year” by Sports Illustrated. In a lengthy feature story in the same magazine in March 1963, the twenty-six-year-old laid out his philosophy that holds true decades later.

“Nothing is impossible,” Penske told writer Gilbert Rogin. “I mean nothing. If they say it’s impossible, it only turns me on. The guy who puts in the most work gets the most results . . . A guy that can take good people and put them together, gets results. . . . The guy sitting back is going to get passed while he’s waiting.”

To this day, the Penske motto remains “Effort Equals Results.”

In the same article, he explained “my success has not been because I’m the best driver. It’s been because I outthink, out-prepare and out-strategy [sic] the next guy.”

From his first foray into racing, Penske had a finely tuned eye for the rulebook. In a constant search for the unfair advantage, he pored over each word and each line for a loophole or gray area to exploit in search of victory. Now, a seemingly simple change offered a chance to grab that advantage.

Historically, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway had allowed a variety of engines under an “equivalency formula.” In racing slang, the early days could be called “run whatcha brung.” The intent was to encourage many types of engines to enter the race and then use the rulebook to attempt to level the competition. Often that meant restrictions to slow down a dominant engine or incentives to improve lesser power-plants. In theory, it was an admirable goal. In reality, there were always certain engines that shone above the rest.

With 1993 in the books, the previous fifteen Indy 500–winning power-plants had been a proven and reliable formula: a specially built turbocharged V8 with four overhead cams and four valves per cylinder. For the 1993 race, the engines from Ilmor (badged as a Chevrolet) and Ford-Cosworth each produced more than 750 horsepower.

Since the mid-1980s, the rulebook had also allowed another engine configuration: a stock engine block produced by an auto manufacturer with a single camshaft and two valves per cylinder with pushrods and rocker arms in the valve train.

To compare a pushrod engine to an overhead cam engine in the most elementary manner, imagine simple eating utensils. Overhead cams are located above the cylinders, which allow direct control of the valves similar to stabbing a piece of meat with a fork. It is direct and controlled. The pushrod system is much more complex. A single camshaft operates valves on both sides of the engine through a series of rods and rockers that are similar to eating with chopsticks. With your hand and fingers acting as the pivoting rocker, chopsticks have more flex, especially under pressure, and less precise control. A pushrod valve at 7,000 RPM activates fifty-eight times per second, so even the smallest additional flex or vibration has devastating results. All other things being equal, an overhead cam with four valves per cylinder is more durable and more powerful.

But all other things were not equal in the Indy rulebook. To make the pushrod engines competitive, the rules allowed a capacity of 209 cubic inches (3.43 liters), an increase of nearly twenty-five percent versus the 161.7 cubic inches (2.65 liters) of the overhead cam engines. The engines were also allowed a higher level of turbocharged boost at 55 inches of manifold pressure (1.863 Bar), an almost twenty percent advantage over the overhead cam engines, which were limited to 45 inches (1.524 Bar). Larger capacity and higher boost mean the same thing: more power.

A number of mostly lower-tier teams had raced the Buick V6 stock-block pushrod engine for nearly a decade. To the frustration of Penske, the heavier engines produced massive power for qualifying, earning the first and second starting positions in 1985 with drivers Pancho Carter and Scott Brayton. As a sign of things to come, both cars dropped out of the race before lap twenty. Buick also powered to the pole position in 1992 with Roberto Guerrero driving. But, on a very cold raceday, Guerrero crashed on the pace lap and never took the green flag. Only one Buick pushrod engine had ever completed the full 200-lap distance, when Al Unser Sr. finished third in the crash-strewn 1992 event. Despite big speed over a few laps, the engines were as brittle as a matchstick in the race.

Tired of such feeble results, Buick and their General Motors brothers at Chevrolet had lobbied USAC and the Speedway to relax the engine rules and allow them to produce a lower-priced, purpose-built American V8 engine that could be more competitive. They presented the sanctioning body with a list of technical details that were quickly adopted as the new regulations.

USAC redefined their rules for a pushrod engine with Clause 115-D. Some details remained static, but eliminating the words “stock block” allowed a special-built racing engine that would have a power advantage without the Achilles heel of a heavy and unreliable block from an assembly line. It meant a designer could add improvements previously made impossible by mass production, such as optimizing the camshaft location, shortening the pushrod length for more control, and maximizing cooling and increasing the engine’s structural strength.

In a dramatic case of the law of unintended consequences, this was like red flashing lights in the eyes of Illien and Morgan. It wasn’t an entirely new topic (the Penske team and Ilmor had discussed the subject for several years), but the relaxed rules opened the door enough for Ilmor and Penske to kick it wide open.

“Paul and I were already convinced we had to do it, and quick,” Illien said about building a pushrod engine for a single race. “There was no doubt about that. I was sure other [engine manufacturers] were thinking about it as well. We felt this was our one chance and we had to do it.”

Illien and Morgan’s concerns about current competitors Ford-Cosworth and Buick building an engine to the new specs were heightened as a worldwide competitor known for sparing no expense announced they would join the Indy car fray in 1994. As an engine supplier in Formula 1, Honda had invested seemingly limitless money and manpower to become dominant, powering six consecutive Constructors’ Championships between the Williams and McLaren F1 teams, and five consecutive Drivers’ Championships with Nelson Piquet, Ayrton Senna, and Alain Prost.

“Honda had enjoyed fantastic success in Formula 1 and our announcement of the Indy car program came on the heels of that success,” explained Robert Clarke, who headed Honda Performance Development Inc., a California-based division built for Honda’s Indy effort. “That’s likely where the fear had come from . . . that we would dominate. That we would spend unlimited amounts of money and we would develop a special team, as we did with McLaren, and just totally dominate.”

Since 1911, no engine had won the pole position and the race in its first appearance. But that only added to the challenge and allure for Illien and Morgan. They must act before the others.

Illien vividly recalled that evening’s discussion over dinner at the Wigwam Resort.

“What do you think we’re going to get on power?” Penske asked.

“At least 900 horsepower, maybe up to 940,” replied Illien, noting their current engine was producing between 760 and 770 horsepower.

“Are you sure?” Penske asked.

“I am absolutely sure. I am convinced of it,” Illien said.

The confident Ilmor duo believed it was a bigger risk to not build the pushrod engine and allow their competitors to bring a bigger, faster bullet to the race. Yet, it was also a huge financial risk, and the timeline to design, build, test, and prove its reliability was incredibly short. Almost impossibly so.

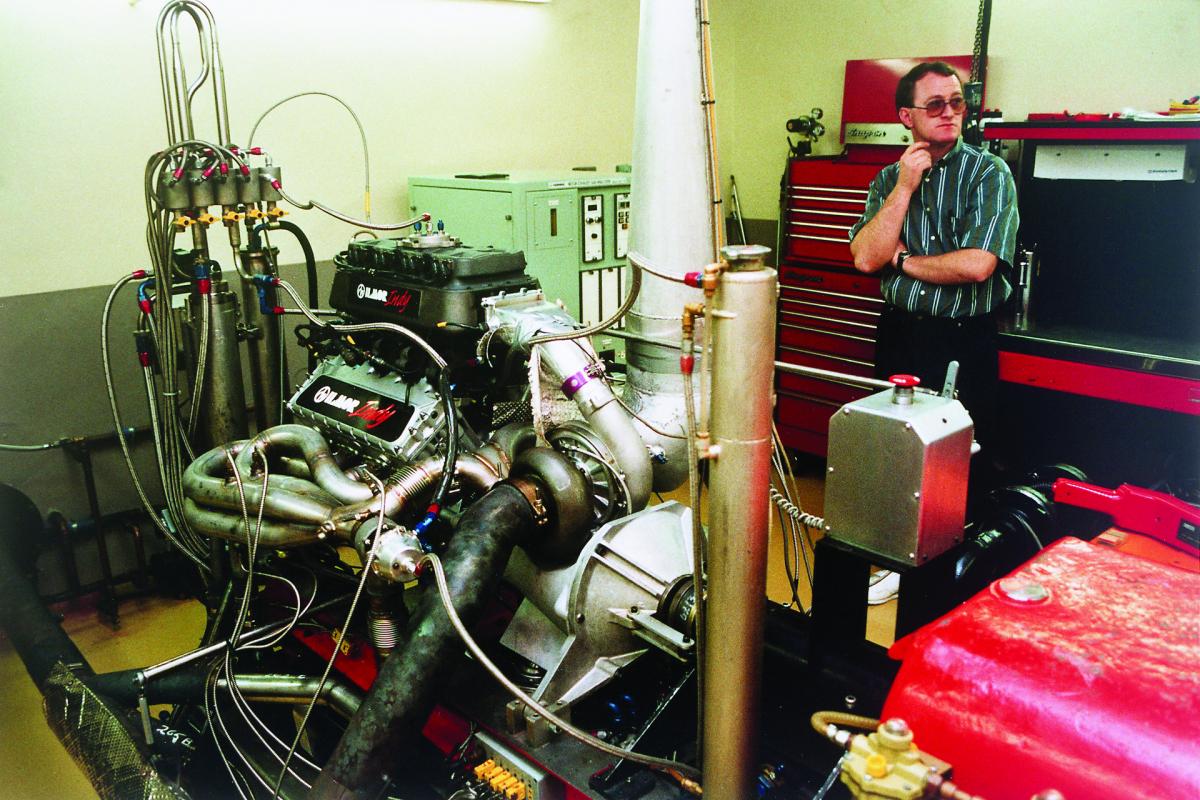

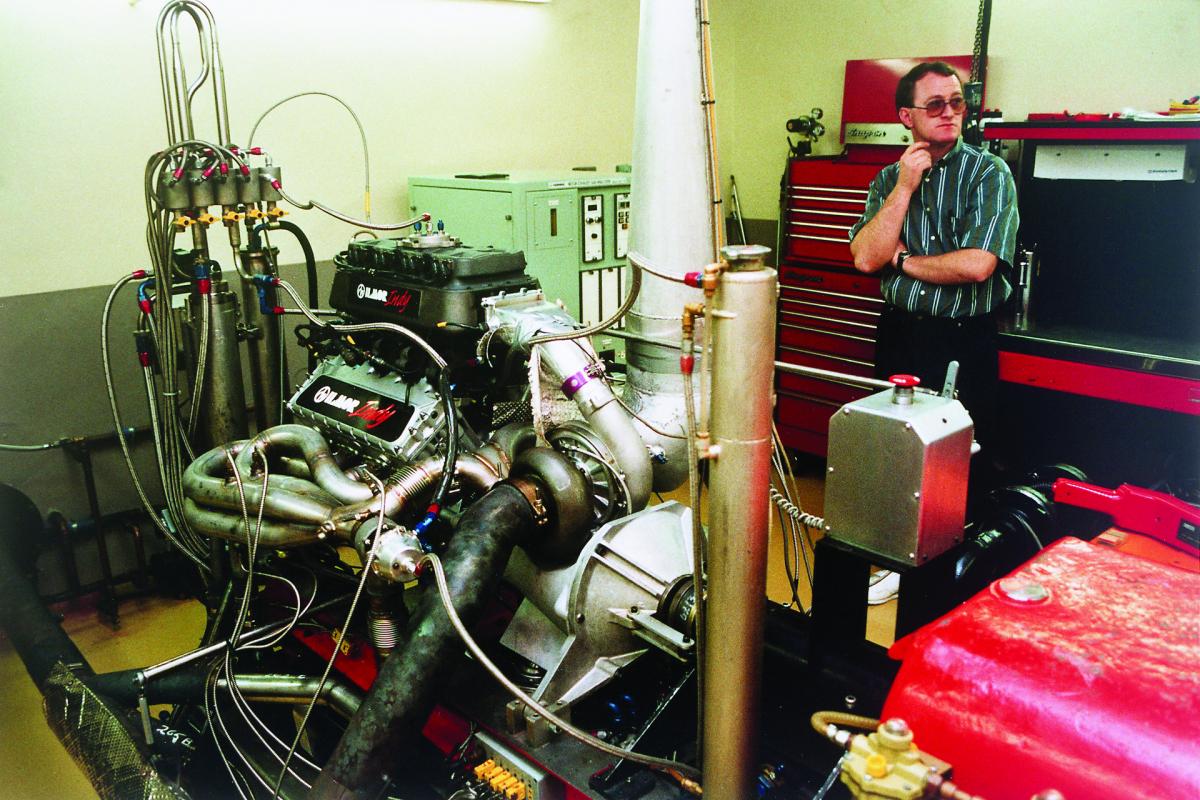

A typical racing engine requires nine months or more from the drawing board to initial startup on a dynamometer. (Better known as a “dyno,” this machine allows an engine to run in a controlled environment while measuring a number of considerations such as torque and horsepower.) Then, a new engine would go through additional months of grueling testing and development on and off the racetrack before and during the race season. With less than eleven months until the next 500, a few quickly penciled calculations meant the new engine would have to be designed and built in six months.

Yet, Illien and Morgan knew they were working with a man who always maintained “nothing is impossible.”

Building an engine that existed only in the fertile imagination of Illien was a strategic gamble; building an all-new chassis to match would only add exponentially to the costs and potential problems. The only option was for the new engine to work with the upcoming 1994 Penske chassis, known as the PC23 (“PC” for Penske Cars and “23” as the next in a long line of beautiful and successful race cars).

In a burst of hubris, Illien made a promise that would put immense pressure on his shoulders and on those of his team of designers for the next several months.

“We’ll design it so it fits exactly in the car like the current engine,” he said.

As they pondered, there was no budget, no written timeline, no contract jammed with legalese. It was merely three men tantalized by a challenge. Each loved nothing more than winning, and this engine deeply appealed to their competitive drives.

Penske had always reached for the unfair advantage, constantly looked for the next innovation that would make his team successful. It was also a forward-thinking business opportunity—the worldwide publicity of his racing victories provided a halo image for his entire business empire and provided a motivating force for thousands of employees who shared emotionally in the success. Corporate sponsors love a winner, and what sponsor would not want to be in business with the man who achieves what his competitors cannot?

For Paul Morgan, the engineering challenge thrilled him, and as the man responsible for the manufacturing side of Ilmor, it was a daring opportunity to make it all work in an extraordinarily short span. For Illien, already considered one of the best designers in the world, it was an intellectual challenge to design a pushrod engine for the first time and prove his expertise in a new and exciting manner.

A wide grin grew across Penske’s face.

“Okay,” he said. “Let’s go.”

For the full story, check out Beast here, and learn how the intrigue, engineering, and utter audacity of three men turned the racing world upside down.

Previous Chapter-Next Chapter

Join our mailing list for specials on the second edition and learn how the intrigue, engineering, and utter audacity of three men turned the racing world upside down. Limited quantities of first edition available.

BEAST: CHAPTER THREE

Nothing Is Impossible

“The word invent, it’s inapt. There’s not one moment where you flip the switch and it starts running. It’s a gradual coalescence of different things, a confluence of energies.”

— Michael Nesmith

Musician, songwriter, filmmaker, and novelist, responding to claims he “invented” MTV (I Want My MTV: The Uncensored Story of the Music Video Revolution)

“I’ll have the rattlesnake,” Mario Illien told the waiter at the luxurious Wigwam Resort in Phoenix, Arizona, in June 1993.

Sitting next to Illien (and his grilled reptile) was fellow engineer Paul Morgan. The two had formed the racing-engine design and manufacturing company Ilmor Engineering Ltd. in November 1983. It wasn’t unusual to find the pair enjoying meals around the globe as a result of their business designing engines for Indy car and Formula 1 race teams. Illien even had an ongoing game of one-upmanship with one of their corporate backers to see who could ring up the largest dinner tab. (Illien won that challenge with an epic postseason meal to celebrate another championship for the Ilmor team.) One of Ilmor’s tenets was never to taunt the racing gods by failing to celebrate your successes properly.

This evening’s meal was more businesslike. They were joined by their third partner, American business magnate and racing legend Roger Penske. Penske had financed Ilmor’s creation a decade before and held a twenty-five percent stake in the company. Less than three weeks before, Penske and Ilmor had won the 1993 Indianapolis 500, and now they were together to discuss plans for next year’s race, slightly more than eleven months away.

It was Penske’s record ninth Indy 500 win as a team owner and his fourth win in the past seven years. His team had also won ten Indy pole positions (the top qualifying position, most likely named because early-twentieth-century American races took place on horse racing tracks, where the fastest horse was placed in the inside starting gate, closest to the poles marking the race distance) and eight Indy car season championships since 1977. His legacy was cemented, but the moment the checkered flag fell on the 1993 race, he began thinking about what it would take to win his tenth.

Morgan and Illien had been deep in thought about the same thing. Their small British company had designed and manufactured the winning engine for the past six races at Indy, including three victories with Team Penske. They were confident that several years of seemingly small changes in engine rules for the 500, set by the United States Auto Club (USAC), the race’s sanctioning body, presented an opportunity to build a new engine that could give them what Penske always called “the unfair advantage.”

By 1993, Penske was the most successful open-wheel race team owner in American history and one of the top business executives in the world as CEO of Detroit Diesel and chairman and CEO of Penske Truck Leasing. His Penske Retail Automotive Group owned auto dealerships featuring most of the major automobile and truck brands. Several of these dealerships were among the largest and most successful in the world. Collectively, they were selling nearly 40,000 vehicles per month.

Born in New Jersey and raised in the Cleveland suburb of Shaker Heights, Ohio, Penske’s love of racing was fueled by a memorable trek with his father to the 1951 Indianapolis 500. He became a superb race-car driver while at Lehigh University. After graduating with a degree in business administration, his fortunes behind the wheel grew. He was selected “1961 Driver of the Year” by Sports Illustrated. In a lengthy feature story in the same magazine in March 1963, the twenty-six-year-old laid out his philosophy that holds true decades later.

“Nothing is impossible,” Penske told writer Gilbert Rogin. “I mean nothing. If they say it’s impossible, it only turns me on. The guy who puts in the most work gets the most results . . . A guy that can take good people and put them together, gets results. . . . The guy sitting back is going to get passed while he’s waiting.”

To this day, the Penske motto remains “Effort Equals Results.”

In the same article, he explained “my success has not been because I’m the best driver. It’s been because I outthink, out-prepare and out-strategy [sic] the next guy.”

From his first foray into racing, Penske had a finely tuned eye for the rulebook. In a constant search for the unfair advantage, he pored over each word and each line for a loophole or gray area to exploit in search of victory. Now, a seemingly simple change offered a chance to grab that advantage.

Historically, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway had allowed a variety of engines under an “equivalency formula.” In racing slang, the early days could be called “run whatcha brung.” The intent was to encourage many types of engines to enter the race and then use the rulebook to attempt to level the competition. Often that meant restrictions to slow down a dominant engine or incentives to improve lesser power-plants. In theory, it was an admirable goal. In reality, there were always certain engines that shone above the rest.

With 1993 in the books, the previous fifteen Indy 500–winning power-plants had been a proven and reliable formula: a specially built turbocharged V8 with four overhead cams and four valves per cylinder. For the 1993 race, the engines from Ilmor (badged as a Chevrolet) and Ford-Cosworth each produced more than 750 horsepower.

Since the mid-1980s, the rulebook had also allowed another engine configuration: a stock engine block produced by an auto manufacturer with a single camshaft and two valves per cylinder with pushrods and rocker arms in the valve train.

To compare a pushrod engine to an overhead cam engine in the most elementary manner, imagine simple eating utensils. Overhead cams are located above the cylinders, which allow direct control of the valves similar to stabbing a piece of meat with a fork. It is direct and controlled. The pushrod system is much more complex. A single camshaft operates valves on both sides of the engine through a series of rods and rockers that are similar to eating with chopsticks. With your hand and fingers acting as the pivoting rocker, chopsticks have more flex, especially under pressure, and less precise control. A pushrod valve at 7,000 RPM activates fifty-eight times per second, so even the smallest additional flex or vibration has devastating results. All other things being equal, an overhead cam with four valves per cylinder is more durable and more powerful.

But all other things were not equal in the Indy rulebook. To make the pushrod engines competitive, the rules allowed a capacity of 209 cubic inches (3.43 liters), an increase of nearly twenty-five percent versus the 161.7 cubic inches (2.65 liters) of the overhead cam engines. The engines were also allowed a higher level of turbocharged boost at 55 inches of manifold pressure (1.863 Bar), an almost twenty percent advantage over the overhead cam engines, which were limited to 45 inches (1.524 Bar). Larger capacity and higher boost mean the same thing: more power.

A number of mostly lower-tier teams had raced the Buick V6 stock-block pushrod engine for nearly a decade. To the frustration of Penske, the heavier engines produced massive power for qualifying, earning the first and second starting positions in 1985 with drivers Pancho Carter and Scott Brayton. As a sign of things to come, both cars dropped out of the race before lap twenty. Buick also powered to the pole position in 1992 with Roberto Guerrero driving. But, on a very cold raceday, Guerrero crashed on the pace lap and never took the green flag. Only one Buick pushrod engine had ever completed the full 200-lap distance, when Al Unser Sr. finished third in the crash-strewn 1992 event. Despite big speed over a few laps, the engines were as brittle as a matchstick in the race.

Tired of such feeble results, Buick and their General Motors brothers at Chevrolet had lobbied USAC and the Speedway to relax the engine rules and allow them to produce a lower-priced, purpose-built American V8 engine that could be more competitive. They presented the sanctioning body with a list of technical details that were quickly adopted as the new regulations.

USAC redefined their rules for a pushrod engine with Clause 115-D. Some details remained static, but eliminating the words “stock block” allowed a special-built racing engine that would have a power advantage without the Achilles heel of a heavy and unreliable block from an assembly line. It meant a designer could add improvements previously made impossible by mass production, such as optimizing the camshaft location, shortening the pushrod length for more control, and maximizing cooling and increasing the engine’s structural strength.

In a dramatic case of the law of unintended consequences, this was like red flashing lights in the eyes of Illien and Morgan. It wasn’t an entirely new topic (the Penske team and Ilmor had discussed the subject for several years), but the relaxed rules opened the door enough for Ilmor and Penske to kick it wide open.

“Paul and I were already convinced we had to do it, and quick,” Illien said about building a pushrod engine for a single race. “There was no doubt about that. I was sure other [engine manufacturers] were thinking about it as well. We felt this was our one chance and we had to do it.”

Illien and Morgan’s concerns about current competitors Ford-Cosworth and Buick building an engine to the new specs were heightened as a worldwide competitor known for sparing no expense announced they would join the Indy car fray in 1994. As an engine supplier in Formula 1, Honda had invested seemingly limitless money and manpower to become dominant, powering six consecutive Constructors’ Championships between the Williams and McLaren F1 teams, and five consecutive Drivers’ Championships with Nelson Piquet, Ayrton Senna, and Alain Prost.

“Honda had enjoyed fantastic success in Formula 1 and our announcement of the Indy car program came on the heels of that success,” explained Robert Clarke, who headed Honda Performance Development Inc., a California-based division built for Honda’s Indy effort. “That’s likely where the fear had come from . . . that we would dominate. That we would spend unlimited amounts of money and we would develop a special team, as we did with McLaren, and just totally dominate.”

Since 1911, no engine had won the pole position and the race in its first appearance. But that only added to the challenge and allure for Illien and Morgan. They must act before the others.

Illien vividly recalled that evening’s discussion over dinner at the Wigwam Resort.

“What do you think we’re going to get on power?” Penske asked.

“At least 900 horsepower, maybe up to 940,” replied Illien, noting their current engine was producing between 760 and 770 horsepower.

“Are you sure?” Penske asked.

“I am absolutely sure. I am convinced of it,” Illien said.

The confident Ilmor duo believed it was a bigger risk to not build the pushrod engine and allow their competitors to bring a bigger, faster bullet to the race. Yet, it was also a huge financial risk, and the timeline to design, build, test, and prove its reliability was incredibly short. Almost impossibly so.

A typical racing engine requires nine months or more from the drawing board to initial startup on a dynamometer. (Better known as a “dyno,” this machine allows an engine to run in a controlled environment while measuring a number of considerations such as torque and horsepower.) Then, a new engine would go through additional months of grueling testing and development on and off the racetrack before and during the race season. With less than eleven months until the next 500, a few quickly penciled calculations meant the new engine would have to be designed and built in six months.

Yet, Illien and Morgan knew they were working with a man who always maintained “nothing is impossible.”

Building an engine that existed only in the fertile imagination of Illien was a strategic gamble; building an all-new chassis to match would only add exponentially to the costs and potential problems. The only option was for the new engine to work with the upcoming 1994 Penske chassis, known as the PC23 (“PC” for Penske Cars and “23” as the next in a long line of beautiful and successful race cars).

In a burst of hubris, Illien made a promise that would put immense pressure on his shoulders and on those of his team of designers for the next several months.

“We’ll design it so it fits exactly in the car like the current engine,” he said.

As they pondered, there was no budget, no written timeline, no contract jammed with legalese. It was merely three men tantalized by a challenge. Each loved nothing more than winning, and this engine deeply appealed to their competitive drives.

Penske had always reached for the unfair advantage, constantly looked for the next innovation that would make his team successful. It was also a forward-thinking business opportunity—the worldwide publicity of his racing victories provided a halo image for his entire business empire and provided a motivating force for thousands of employees who shared emotionally in the success. Corporate sponsors love a winner, and what sponsor would not want to be in business with the man who achieves what his competitors cannot?

For Paul Morgan, the engineering challenge thrilled him, and as the man responsible for the manufacturing side of Ilmor, it was a daring opportunity to make it all work in an extraordinarily short span. For Illien, already considered one of the best designers in the world, it was an intellectual challenge to design a pushrod engine for the first time and prove his expertise in a new and exciting manner.

A wide grin grew across Penske’s face.

“Okay,” he said. “Let’s go.”

For the full story, check out Beast here, and learn how the intrigue, engineering, and utter audacity of three men turned the racing world upside down.

Previous Chapter-Next Chapter