Beast Two: Absolute Time

Chapter 2 from Beast by Jade Gurss

In anticipation of the April 1, 2020 release of the revised, second edition, Octane Press is releasing excerpts from the award-winning book Beast: The Top Secret Ilmor Penske Engine that Shocked the Racing World at the Indy 500.

Join our mailing list for pre-order specials on the second edition and learn how the intrigue, engineering, and utter audacity of three men turned the racing world upside down. Limited quantities of first edition available.

BEAST: CHAPTER TWO

Domination Does Not Matter

“Time is of the essence . . . and I’m very short of essence.”

— Graham Hill, OBE

Formula 1 champion, 1962 and 1968; Indianapolis 500 winner, 1966 (as a rookie)

Auto racing is governed by a simple idea: The race is won by the car that covers a given distance in the least amount of time.

In the 1912 Indianapolis 500, Ralph DePalma cruised past Teddy Tetzlaff to lead the third lap in his No. 4 Mercedes, a car legendarily known as the Grey Ghost. DePalma was not passed for 196 laps, building a lead of 5 laps (more than 12.5 miles) until a broken connecting rod brought the Italian-born driver’s car to a stop with the checkered flag slightly more than a lap away.

DePalma and his equally brave riding mechanic, Rupert Jeffkins, exhausted and covered in grit and soot, climbed out to gallantly push their crippled car down the long front straightaway as Joe Dawson and his riding mechanic, Harry Martin, drove past them into the history books, winning the race by leading only the final two laps. (DePalma would win the 1915 race in the same Mercedes; Dawson would never lead another lap at Indy.)

Fifty-five years later, Parnelli Jones, the 1963 Indy 500 winner and huge fan favorite, began the 1967 race from the sixth position in the STP Oil Treatment Special, a retina-burning fluorescent-orange “Whooshmobile,” a jet-turbine-powered, four-wheel-drive car unlike anything the Speedway had seen. Jones took the lead before the halfway point of the first lap. Grinning devilishly, he waved to his rival Mario Andretti as he whooshed past. Mario gave Parnelli the finger in return. Completing the opening lap, Jones casually raised his right hand to flash the “Okay” sign to his team.

Jones led 171 laps, seemingly at will, and was at the head of the field by nearly a complete lap until a six-dollar gearbox bearing failed on lap 196. (Six dollars!) Jones and the Pratt & Whitney turbine coasted silently into the pit lane while A. J. Foyt streamed past to score the third of his four Indy 500 triumphs.

Two decades later, Andretti seemed destined to end almost twenty years of frustration in the 1987 Indianapolis 500. After his victory in 1969, Andretti’s luck at Indy had nearly always been bad. But paired with brilliant engineer Adrian Newey at the Newman/Haas team, Andretti was racing with a Chevrolet engine designed and built by Ilmor Engineering. This looked to be the first 500 win for Ilmor, a very new company, and for the Newman/Haas team.

In his bright-red racer, Andretti easily led 170 of the first 180 laps, when the engine failed because he drove too slowly!

“I so dominated that race easily,” Andretti said recently, “and I was so far ahead, I ran the car too easily!"

“We had several top gears, one that you would run really hard if you were in a battle, and then a slightly higher gear where you could save the engine a little bit,” Andretti explained. “Franz Weis, our engine man, kept telling me to keep the revs down. Now, I have been accused in the past of killing my equipment because I pushed so hard, so I was just taking it easy. But I began to feel a slight vibration in the car. I wasn’t sure how much to be worried about it because I told myself that I was taking it easy on everything.

“I was taking it easy at lower RPMs, which were the exact revs that the engine had some strange harmonics and came apart,” Andretti recalled with obvious disappointment.

Any object has a natural frequency that causes it to vibrate vigorously, just as a tuning fork resonates when tapped on a table. A valve spring is similar to a tuning fork, but it’s coiled. When it hits its natural frequency and gets excited, it surges (like flicking a Slinky down stairs) and the coils move like a wave up and down its length. At certain RPMs this can be so severe that the bottom of the spring jumps off its platform, which can cause engine failure.

“After the race, Ilmor replicated my run on their dyno,” Andretti recalled. “My team manager, Tyler Alexander, was there to witness the test. They used all of the data from my car, and the test engine failed pretty quickly in exactly the same way. They tell me if I would have run 600—600!—revs more, the engine would have continued to run perfectly and easily taken me to the win.”

When Andretti’s engine failed, Al Unser became the second man to claim four Indy 500 titles. It was his most unlikely win, driving a Roger Penske entry with a Cosworth engine.

Each of these examples proves one thing: Domination does not matter. Winning does. And that means finishing the race.

With the guiding law of a given distance in the least amount of time, the business of auto racing is conducted in “absolute time.” Absolute time determines the winners and losers, and has done so since the first humans challenged each other to a foot race many thousands of years ago. An auto race scheduled to begin Sunday at 1 p.m. will absolutely start then and will absolutely begin with or without you. Thousands of fans in the grandstands and millions watching on television demand it (barring extreme weather or a critical situation).

To be successful, every person on a race team must be prepared. There are no options, no excuses, no opportunities to delay the preparation by one day, one hour, or one minute. The moment a team member relaxes is the moment their opponent in the next garage or the next driver on the track is pushing harder. The winners are usually those most prepared when the race begins.

A successful racing driver possesses an innate sense of absolute timing. He or she is at peril, with mistakes having severe, sometimes permanent, consequences. Their decision-making and reflexes must be honed for movements measured in hundredths of a second. For several decades at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, speeds have exceeded 230 miles per hour on the straightaways and only slightly less in the corners. A car hurtling around the track covers more than the length of a soccer pitch or football field every second. Close your eyes and imagine that. Every second. For 500 miles.

Blazing speeds are a huge part of the sexy, dangerous allure of auto racing, yet top speed is merely one piece of an elaborate jigsaw puzzle. Braking, gearing, fuel mileage, pit stops, tire grip, driver skill, and an occasional dose of luck are all pieces that must fit together perfectly to achieve the best possible results.

The stopwatch is the most exacting measure of absolute time, as it measures increments of thousandths of a second or less. You cannot bullshit the stopwatch. It has neither emotion nor a political agenda. It plays no favorites. You cannot fool the stopwatch. Style and sentiment have no effect. It is the ultimate judge. It tells the absolute truth.

The best-kept secret in Indy 500 history was achieved by people on two continents who share immense cubic inches of brainpower and a boundless work ethic, driven by visionary and demanding leaders. It was achieved by brilliant designers, engineers, and mechanics, all of whom were immersed daily in absolute numbers. The laws of physics and fluid dynamics govern their profession, but a successful race team finds magic between those hard numbers. Racers always look for spaces in the rules where they can maximize their chances to win. In this case, the team didn’t need a gray area or loophole. They secretly built an imposing engine that matched the spirit and the letter of the Indy 500 rulebook.

Their absolute target was 10:52 a.m. on Sunday, May 29, 1994, at the seventy-eighth running of “The Greatest Spectacle in Racing” in Speedway, Indiana. That was the moment when the magical command (created in the early 1950s at this very speedway and amended slightly to recognize the female driver in the field) was given.

“Lady and Gentlemen, Start . . . Your . . . EN-gines!”

For the full story, check out Beast here, and learn how the intrigue, engineering, and utter audacity of three men turned the racing world upside down.

Previous Chapter-Next Chapter

Join our mailing list for pre-order specials on the second edition and learn how the intrigue, engineering, and utter audacity of three men turned the racing world upside down. Limited quantities of first edition available.

BEAST: CHAPTER TWO

Domination Does Not Matter

“Time is of the essence . . . and I’m very short of essence.”

— Graham Hill, OBE

Formula 1 champion, 1962 and 1968; Indianapolis 500 winner, 1966 (as a rookie)

Auto racing is governed by a simple idea: The race is won by the car that covers a given distance in the least amount of time.

In the 1912 Indianapolis 500, Ralph DePalma cruised past Teddy Tetzlaff to lead the third lap in his No. 4 Mercedes, a car legendarily known as the Grey Ghost. DePalma was not passed for 196 laps, building a lead of 5 laps (more than 12.5 miles) until a broken connecting rod brought the Italian-born driver’s car to a stop with the checkered flag slightly more than a lap away.

DePalma and his equally brave riding mechanic, Rupert Jeffkins, exhausted and covered in grit and soot, climbed out to gallantly push their crippled car down the long front straightaway as Joe Dawson and his riding mechanic, Harry Martin, drove past them into the history books, winning the race by leading only the final two laps. (DePalma would win the 1915 race in the same Mercedes; Dawson would never lead another lap at Indy.)

Fifty-five years later, Parnelli Jones, the 1963 Indy 500 winner and huge fan favorite, began the 1967 race from the sixth position in the STP Oil Treatment Special, a retina-burning fluorescent-orange “Whooshmobile,” a jet-turbine-powered, four-wheel-drive car unlike anything the Speedway had seen. Jones took the lead before the halfway point of the first lap. Grinning devilishly, he waved to his rival Mario Andretti as he whooshed past. Mario gave Parnelli the finger in return. Completing the opening lap, Jones casually raised his right hand to flash the “Okay” sign to his team.

Jones led 171 laps, seemingly at will, and was at the head of the field by nearly a complete lap until a six-dollar gearbox bearing failed on lap 196. (Six dollars!) Jones and the Pratt & Whitney turbine coasted silently into the pit lane while A. J. Foyt streamed past to score the third of his four Indy 500 triumphs.

Two decades later, Andretti seemed destined to end almost twenty years of frustration in the 1987 Indianapolis 500. After his victory in 1969, Andretti’s luck at Indy had nearly always been bad. But paired with brilliant engineer Adrian Newey at the Newman/Haas team, Andretti was racing with a Chevrolet engine designed and built by Ilmor Engineering. This looked to be the first 500 win for Ilmor, a very new company, and for the Newman/Haas team.

In his bright-red racer, Andretti easily led 170 of the first 180 laps, when the engine failed because he drove too slowly!

“I so dominated that race easily,” Andretti said recently, “and I was so far ahead, I ran the car too easily!"

“We had several top gears, one that you would run really hard if you were in a battle, and then a slightly higher gear where you could save the engine a little bit,” Andretti explained. “Franz Weis, our engine man, kept telling me to keep the revs down. Now, I have been accused in the past of killing my equipment because I pushed so hard, so I was just taking it easy. But I began to feel a slight vibration in the car. I wasn’t sure how much to be worried about it because I told myself that I was taking it easy on everything.

“I was taking it easy at lower RPMs, which were the exact revs that the engine had some strange harmonics and came apart,” Andretti recalled with obvious disappointment.

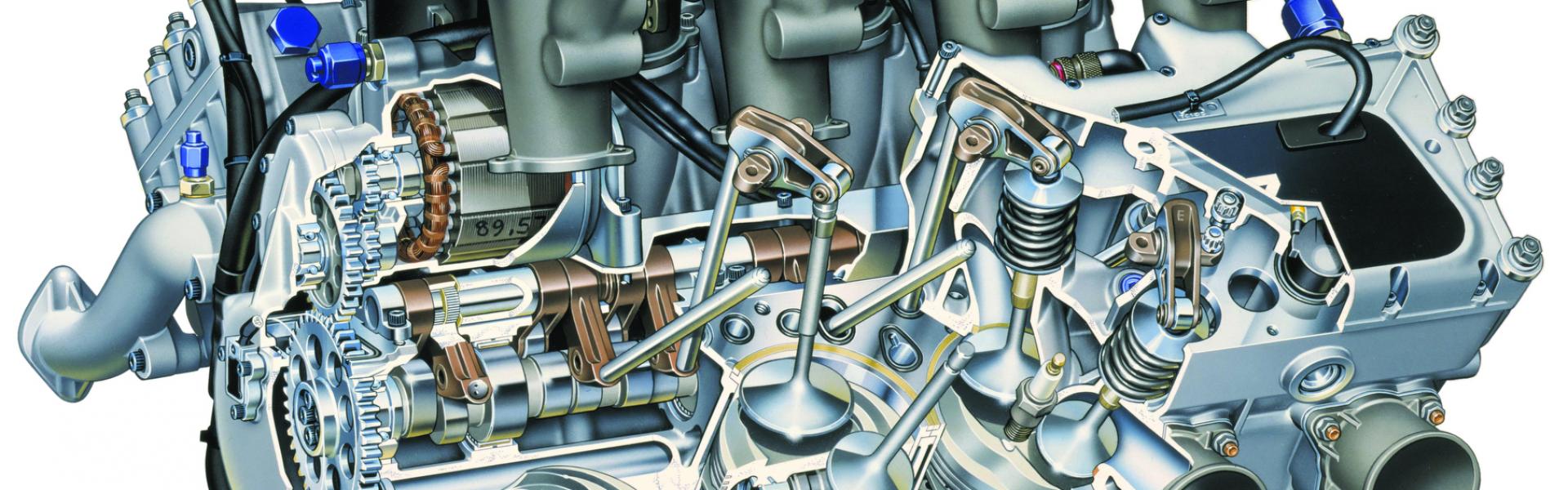

Any object has a natural frequency that causes it to vibrate vigorously, just as a tuning fork resonates when tapped on a table. A valve spring is similar to a tuning fork, but it’s coiled. When it hits its natural frequency and gets excited, it surges (like flicking a Slinky down stairs) and the coils move like a wave up and down its length. At certain RPMs this can be so severe that the bottom of the spring jumps off its platform, which can cause engine failure.

“After the race, Ilmor replicated my run on their dyno,” Andretti recalled. “My team manager, Tyler Alexander, was there to witness the test. They used all of the data from my car, and the test engine failed pretty quickly in exactly the same way. They tell me if I would have run 600—600!—revs more, the engine would have continued to run perfectly and easily taken me to the win.”

When Andretti’s engine failed, Al Unser became the second man to claim four Indy 500 titles. It was his most unlikely win, driving a Roger Penske entry with a Cosworth engine.

Each of these examples proves one thing: Domination does not matter. Winning does. And that means finishing the race.

With the guiding law of a given distance in the least amount of time, the business of auto racing is conducted in “absolute time.” Absolute time determines the winners and losers, and has done so since the first humans challenged each other to a foot race many thousands of years ago. An auto race scheduled to begin Sunday at 1 p.m. will absolutely start then and will absolutely begin with or without you. Thousands of fans in the grandstands and millions watching on television demand it (barring extreme weather or a critical situation).

To be successful, every person on a race team must be prepared. There are no options, no excuses, no opportunities to delay the preparation by one day, one hour, or one minute. The moment a team member relaxes is the moment their opponent in the next garage or the next driver on the track is pushing harder. The winners are usually those most prepared when the race begins.

A successful racing driver possesses an innate sense of absolute timing. He or she is at peril, with mistakes having severe, sometimes permanent, consequences. Their decision-making and reflexes must be honed for movements measured in hundredths of a second. For several decades at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, speeds have exceeded 230 miles per hour on the straightaways and only slightly less in the corners. A car hurtling around the track covers more than the length of a soccer pitch or football field every second. Close your eyes and imagine that. Every second. For 500 miles.

Blazing speeds are a huge part of the sexy, dangerous allure of auto racing, yet top speed is merely one piece of an elaborate jigsaw puzzle. Braking, gearing, fuel mileage, pit stops, tire grip, driver skill, and an occasional dose of luck are all pieces that must fit together perfectly to achieve the best possible results.

The stopwatch is the most exacting measure of absolute time, as it measures increments of thousandths of a second or less. You cannot bullshit the stopwatch. It has neither emotion nor a political agenda. It plays no favorites. You cannot fool the stopwatch. Style and sentiment have no effect. It is the ultimate judge. It tells the absolute truth.

The best-kept secret in Indy 500 history was achieved by people on two continents who share immense cubic inches of brainpower and a boundless work ethic, driven by visionary and demanding leaders. It was achieved by brilliant designers, engineers, and mechanics, all of whom were immersed daily in absolute numbers. The laws of physics and fluid dynamics govern their profession, but a successful race team finds magic between those hard numbers. Racers always look for spaces in the rules where they can maximize their chances to win. In this case, the team didn’t need a gray area or loophole. They secretly built an imposing engine that matched the spirit and the letter of the Indy 500 rulebook.

Their absolute target was 10:52 a.m. on Sunday, May 29, 1994, at the seventy-eighth running of “The Greatest Spectacle in Racing” in Speedway, Indiana. That was the moment when the magical command (created in the early 1950s at this very speedway and amended slightly to recognize the female driver in the field) was given.

“Lady and Gentlemen, Start . . . Your . . . EN-gines!”

For the full story, check out Beast here, and learn how the intrigue, engineering, and utter audacity of three men turned the racing world upside down.

Previous Chapter-Next Chapter