Beast Six: Design-Driven

Chapter 6 from Beast by Jade Gurss

To celebrate the release of the revised, second edition, Octane Press is releasing excerpts from the award-winning book Beast: The Top Secret Ilmor Penske Engine that Shocked the Racing World at the Indy 500.

Join our mailing list for specials on the second edition and learn how the intrigue, engineering, and utter audacity of three men turned the racing world upside down. Limited quantities of first edition available.

BEAST: CHAPTER SIX

JFDI

“Some say the cup is half empty, while others say it is half full. However, in my opinion, both are wrong. The real problem is the cup is too big.”

— Donald Coduto, describing the thought process of an engineer in Foundation Design

Under the cloud of mistrust between the Speedway and CART, Penske and Ilmor began planning an engine they hoped would dominate. Illien and Morgan returned to England and met individually with their design staff, explaining the challenge ahead. The timeframe was critical and secrecy was imperative.

A single line in the USAC rulebook haunted Morgan, Illien, and Penske, and drove their focus on secrecy. Clause 118-D stated, “USAC reserves the right to alter manifold pressure settings for any event.” This meant the sanctioning body could lower the boost level at any time, even in the days before the race, which would dramatically reduce the power from the engine. If word were to leak, Penske and Ilmor believed USAC could act to ban it. Or their competitors could design one of their own. The project was speculative and risked being shelved at any time if there were delays or failures. It must be done swiftly and correctly the first time.

It was a massive undertaking under any circumstances, but it was far from Ilmor’s sole focus. They were still in the midst of ongoing engine development and problem-solving for the current race seasons in CART and Formula 1, as well as designing new engines for both series for the upcoming year! Any of those undertakings alone demanded full-time focus; adding a mammoth new project for a single race meant an unprecedented effort.

But Illien had deep confidence in his design team, trusting them to do their respective jobs without constant oversight or micromanagement.

“There wasn’t room for discussion,” Illien said. “I had worked with these people and they knew what I wanted, what I was expecting, and not everything had to be told. They knew the way we were working and that helped bring things together. It was quite clear that we had to run it [for the first time] in January. We would stretch a day into a week to achieve it. It wasn’t laid out in a comprehensive [timeline]; we knew what we had to do. With few people getting involved, it wasn’t such a big issue because we all sat in the same office and we just pushed on.”

“I had a rubber stamp made up that just had ‘JFDI’ on it,” said Robin Page, who worked in the design office and was Ilmor’s at-track engineer for the pushrod project. “That was for ‘Just Fucking Do It!’ Let’s not talk about it, let’s just fucking do it! I would put that on drawings and documents: JFDI.”

Illien and his team had never designed a pushrod engine, but the biggest hurdle was living up to his insistence that the engine fit into the race car exactly like the “normal” engine.

“That’s a commitment I made to Roger at the Wigwam before I even had a line on paper,” explained Illien. “I said the engine would fit the existing car. The water coolers, oil coolers, and all the outlets would be in the same positions so we wouldn’t have to build another car. I said I would make it the same length as well so the gearbox would work and everything would come together as easy as possible.”

It was also a safety net: The standard engine could be reinstalled in the cars if the pushrod was a failure.

Why was the size and fit so critical? Most passenger cars, NASCAR-style stock cars, and production-based sports cars have engines that are inserted inside a skeletal frame or chassis. In direct contrast, the engine in an Indy car becomes an integral part of the chassis: It is the rear spine of the car. The front of an Indy car chassis is a strong and light carbon-fiber tub, providing the structure for the car and the safety capsule for the driver. Behind the fuel tank is a firewall for safety, and the engine is mounted behind it. The gearbox assembly (which includes the rear suspension, both axles and wheels, and the rear wing) is attached directly to the engine. So the engine not only powers the car, but as an integral part of the chassis, it must also have the rigidity to withstand immense forces from these attached components.

With top speeds over 230 miles per hour at Indy, the engine must also fit into the critical aerodynamic design of the entire car. It must be as light and compact as possible, with a very low center of gravity. While the “regular” engine was 161.7 cubic inches, the pushrod engine would be 209 cubic inches. To fit it into the same space would be like forcing thirty-seven gallons of fuel into a thirty-gallon tank.

“Obviously that commitment made it quite challenging,” Illien said. “Because when I really got down to it, it was not straightforward how to package everything in that space. The length was the biggest issue. I really struggled to get it . . . because it was a bigger engine. That was the biggest challenge I had: the packaging.”

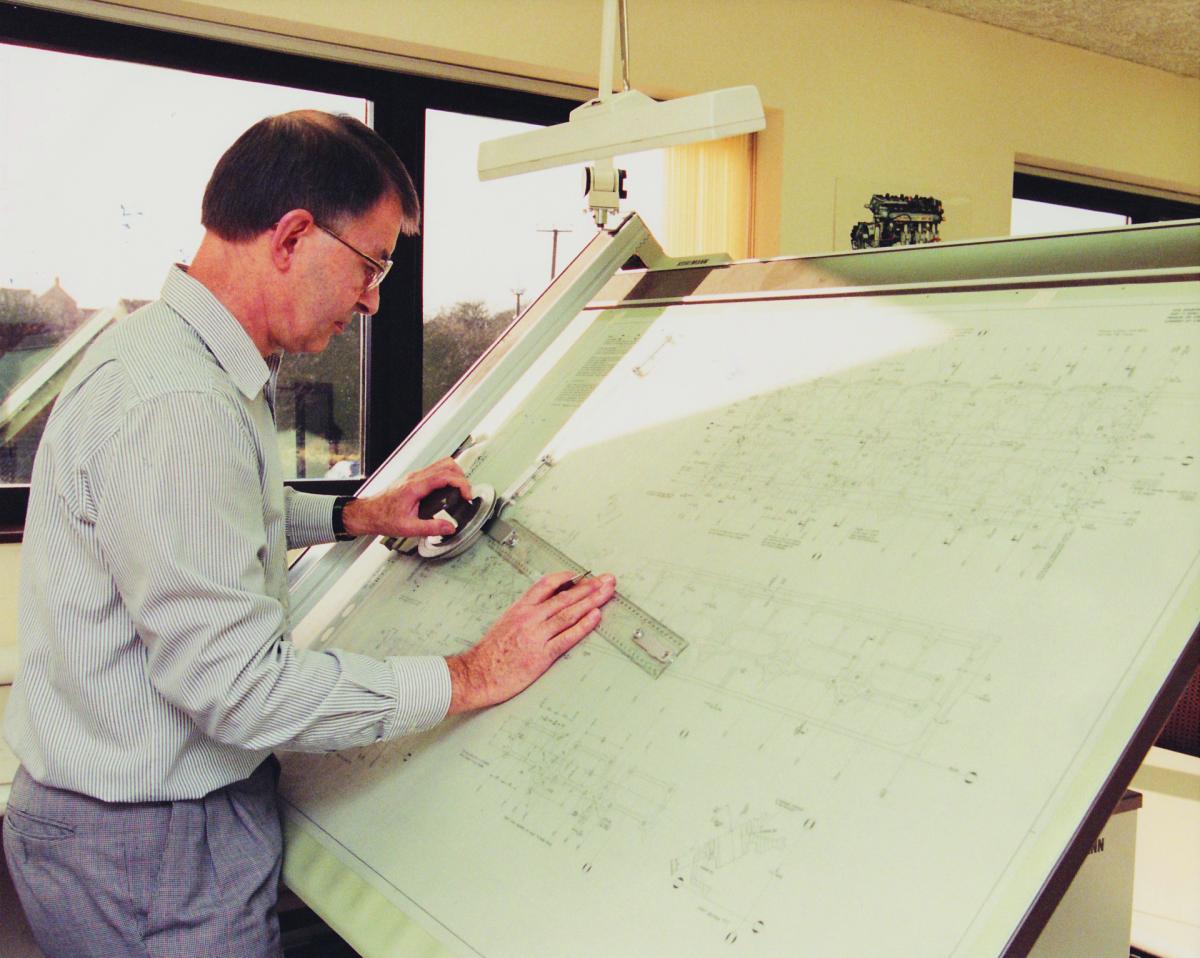

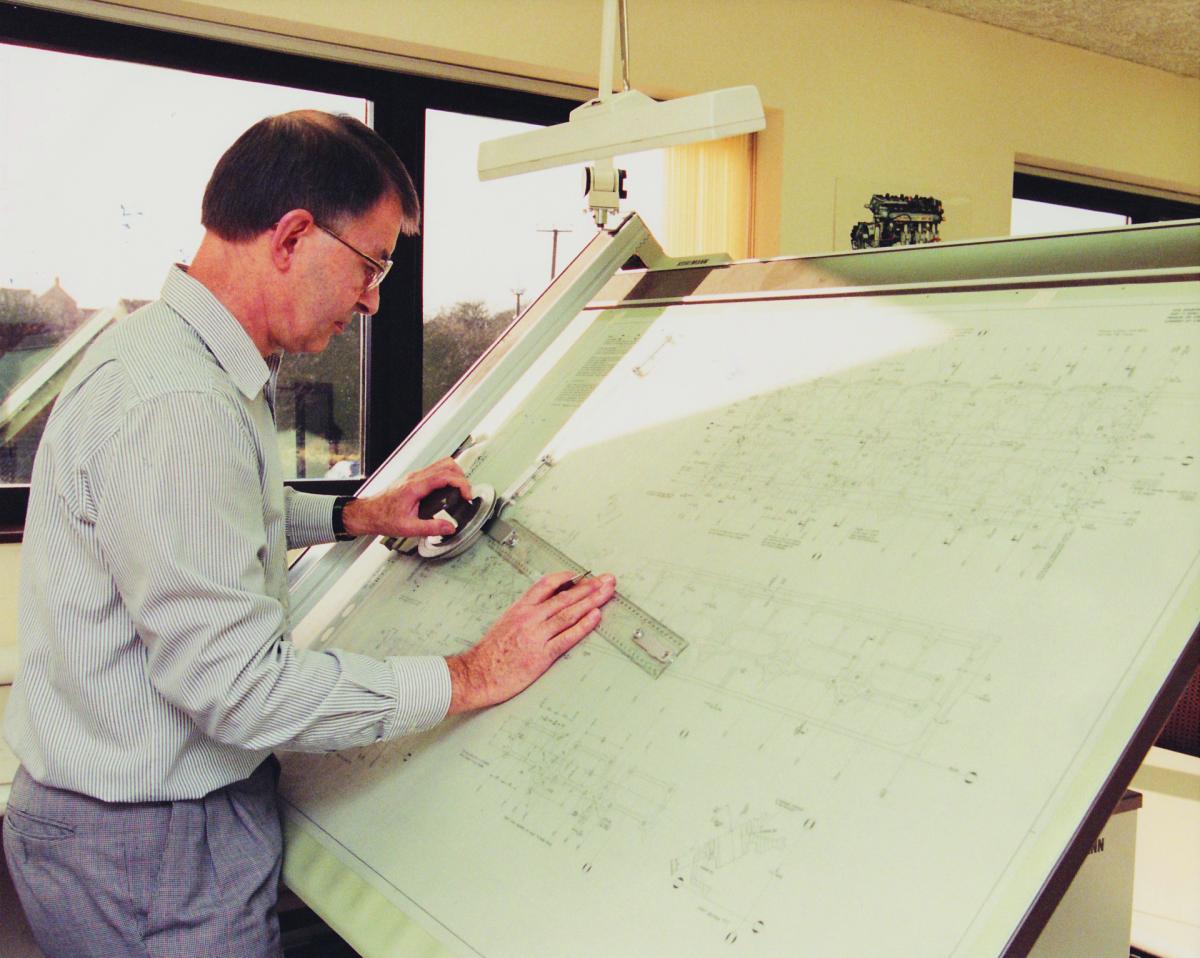

Illien sat at his drawing board, pencil in hand, to determine things like the ideal bore and stroke, the V-angle for the cylinders, and the overall size of the engine. Illien worked purely by hand as computer-aided design (CAD) was in its infancy in 1993. (In the hands of several of Ilmor’s designers CAD became essential later in the design process.)

“The major parameters I set down,” Illien said. “I made some schemes on my drawing board so they were very defined and very clear. There was not much freedom because time was the other issue. We just had to go and move forward.”

Mario Illien was born in Chur, Switzerland, in August 1949. Alpine skiing was the preeminent sport in the small town surrounded by the Alps and adjacent to the Rhine River. His home country banned all motorsports activity in 1955 following the most horrendous auto-racing crash ever at LeMans, France, where eighty-three people were killed. Illien’s family didn’t even own an automobile. In Chur, walking or skiing was the preferred method of transportation.

“I don’t know what really sparked [my passion],” said Illien. “But from a very early age I was interested in motorcars and engines. We would play games behind walls and when cars would go by, we would try to recognize the car and model from the sound of the engine. I just was fascinated by cars, particularly the engines. I don’t think it was the fact that we didn’t have a car—there wasn’t any car around to try things on—but I was fascinated by it.”

As a teenager, his reading gravitated toward racing, especially Formula 1.

“I was interested in it, something I had a passion for,” he said. “I didn’t know how I’d get into it ultimately, but there was definitely a desire to do so.”

Illien studied as a technical draftsman until his early twenties when he became a mechanic for Swedish-born driver Joakim “Jo” Bonnier, a brainy man who spoke six languages and studied at Oxford before moving to Paris. Bonnier had a lengthy career in Formula 1 and sports cars, and he found a kindred spirit in Illien, who also spoke multiple languages and clearly possessed an immense intellect.

Sadly, Bonnier was killed in a crash at LeMans in 1972, and the young Illien was forced to move on. He designed a Chrysler Simca Formula 2 engine and another for a motorcycle sidecar racer before he graduated from the Biel University Engineering School in Switzerland with a degree in mechanical engineering in 1976.

After several years designing diesel engines in Switzerland, Illien joined Cosworth Engineering in Northamptonshire, England. Formed by Mike Costin and Keith Duckworth in 1958, Cosworth is one of the top Formula 1 engine companies in history, ranking second only to Ferrari in all-time victories. Debuting in 1966, the Cosworth DFV (Double Four Valve) engine, backed by Ford Motor Company, ruled Formula 1 for nearly fifteen years. Illien initially joined Cosworth to design the evolutionary DFY Formula 1 engine, and also worked on the Indy car engine known as the DFX.

Illien became close friends with another engineer who had been with Cosworth since 1970, a man named Paul Morgan, who was working on the company’s Indy car program.

Why was their friendship and work combination so potent?

“To be engineers and to be able to discuss things and at the same time complement each other in many, many ways,” Illien said. “I think that’s what made it possible.”

The two engineers realized Cosworth’s Indy car engine was not being properly developed. Yet, because of their almost complete monopoly on the CART series, Cosworth wasn’t particularly interested in spending the money to make the improvements proposed by the two engineers.

Convinced they could do better, the two conceived their own Indy car-engine design company. Both were mature enough to handle a new business, but still young and energetic enough to make it work.

“We had worked together on things at Cosworth,” said Illien. “I drew many things for the Cosworth engines and he had them made. We also made a Norton motorcycle engine. Somebody bought that thing and wanted fuel injection and more power to go racing so that became our project. We had a lot of interesting projects together and we knew we could work together. That was the start.”

They had the ideas but lacked a financial backer. In Morgan’s time with the Indy car series in America, he had developed a friendly relationship with Roger Penske, so Morgan called Penske to gauge his interest. When Penske asked for further details, Morgan and Illien, along with their wives, Liz and Catherine, began preparing a document with estimated expenses to create the facility, as well as a timeline to design and build a racing engine for the 1986 season.

From the living room of the Morgan home in Brixworth, the four created a thirty-page handwritten document for Penske. As no copier was available, they took photographs of each page to serve as their record of the proposal. On October 13, 1983, they sent it to Penske via FedEx despite their concern at the considerable expense of paying for an overnight letter out of their own pockets.

In the 1999 book Ilmor: The First 15 Years (printed by Ilmor solely for their employees and corporate sponsors), Illien described the process with Penske, as “a telephone call, a meeting and a handshake. And off we went!”

It wasn’t quite that simple. Penske wanted a fifty percent stake in the company with Illien and Morgan each getting twenty-five percent. Though they initially balked, the pair eventually agreed to sign the contract with Penske on November 22, 1983. Even though their duties would always overlap, Penske defined everyone’s role to make it easier for most to understand: Illien was chief designer, while Morgan was in charge of vendors and manufacturing. Penske was responsible for finding a benefactor for the company.

“Those were the three main goals: running the business, designing the engine and developing an association with a world-class manufacturer,” Penske said in the same Ilmor history book.

Penske eventually interested General Motors and its Chevrolet brand, arguing that a partnership with an Indy car program could help Chevrolet showcase innovation and performance.

The first meeting of GM, Penske, and Ilmor took place in the Morgan home, known as The Brown House, despite Liz Morgan’s horror at not having a “proper” kitchen. Regardless of her worries, the meeting went well. A second meeting was set for October 12, 1984, in Detroit. The lawyers had prepared all the documents and contracts with that date, but the meeting didn’t begin until evening. With the final details to be worked out, tension began to build as midnight neared.

Paul Morgan solved the time problem a few minutes before midnight by reaching for the clock in the room and removing the batteries. Now they could work all night and it would still be October 12! Around four o’clock in the morning, the documents were signed.

General Motors had taken an extraordinary risk, trusting Penske enough to become a partner in a new design company located in the midlands of England. In return, GM received a twenty-five percent share of the company, taken from Penske’s allotment.

The Chevrolet Indy V8/A engine roared to life on the new dyno at Ilmor in May 1985. In August of that year, Rick Mears was the first to drive a Penske chassis with Ilmor power. Mears was not only a championship racer, he was one of the best test drivers, able to assess a chassis and engine very quickly. When Mears put his right foot down, he instantly knew the engine was a winner.

While the early days were fraught with reliability issues between the Ilmor engine and Penske chassis, the engine made its racing debut at Phoenix on April 6, 1986. Al Unser Sr. qualified seventh, but the start of the race proved inauspicious. The engine wouldn’t fire. Finally a dead battery was replaced and Unser joined the fray four laps late. Before retiring from the race due to a crash, Unser ran a number of laps quicker than the race leaders, serving notice that a new contender had arrived in Indy car racing.

For the full story, check out Beast here, and learn how the intrigue, engineering, and utter audacity of three men turned the racing world upside down.

Previous Chapter-Next Chapter

Join our mailing list for specials on the second edition and learn how the intrigue, engineering, and utter audacity of three men turned the racing world upside down. Limited quantities of first edition available.

BEAST: CHAPTER SIX

JFDI

“Some say the cup is half empty, while others say it is half full. However, in my opinion, both are wrong. The real problem is the cup is too big.”

— Donald Coduto, describing the thought process of an engineer in Foundation Design

Under the cloud of mistrust between the Speedway and CART, Penske and Ilmor began planning an engine they hoped would dominate. Illien and Morgan returned to England and met individually with their design staff, explaining the challenge ahead. The timeframe was critical and secrecy was imperative.

A single line in the USAC rulebook haunted Morgan, Illien, and Penske, and drove their focus on secrecy. Clause 118-D stated, “USAC reserves the right to alter manifold pressure settings for any event.” This meant the sanctioning body could lower the boost level at any time, even in the days before the race, which would dramatically reduce the power from the engine. If word were to leak, Penske and Ilmor believed USAC could act to ban it. Or their competitors could design one of their own. The project was speculative and risked being shelved at any time if there were delays or failures. It must be done swiftly and correctly the first time.

It was a massive undertaking under any circumstances, but it was far from Ilmor’s sole focus. They were still in the midst of ongoing engine development and problem-solving for the current race seasons in CART and Formula 1, as well as designing new engines for both series for the upcoming year! Any of those undertakings alone demanded full-time focus; adding a mammoth new project for a single race meant an unprecedented effort.

But Illien had deep confidence in his design team, trusting them to do their respective jobs without constant oversight or micromanagement.

“There wasn’t room for discussion,” Illien said. “I had worked with these people and they knew what I wanted, what I was expecting, and not everything had to be told. They knew the way we were working and that helped bring things together. It was quite clear that we had to run it [for the first time] in January. We would stretch a day into a week to achieve it. It wasn’t laid out in a comprehensive [timeline]; we knew what we had to do. With few people getting involved, it wasn’t such a big issue because we all sat in the same office and we just pushed on.”

“I had a rubber stamp made up that just had ‘JFDI’ on it,” said Robin Page, who worked in the design office and was Ilmor’s at-track engineer for the pushrod project. “That was for ‘Just Fucking Do It!’ Let’s not talk about it, let’s just fucking do it! I would put that on drawings and documents: JFDI.”

Illien and his team had never designed a pushrod engine, but the biggest hurdle was living up to his insistence that the engine fit into the race car exactly like the “normal” engine.

“That’s a commitment I made to Roger at the Wigwam before I even had a line on paper,” explained Illien. “I said the engine would fit the existing car. The water coolers, oil coolers, and all the outlets would be in the same positions so we wouldn’t have to build another car. I said I would make it the same length as well so the gearbox would work and everything would come together as easy as possible.”

It was also a safety net: The standard engine could be reinstalled in the cars if the pushrod was a failure.

Why was the size and fit so critical? Most passenger cars, NASCAR-style stock cars, and production-based sports cars have engines that are inserted inside a skeletal frame or chassis. In direct contrast, the engine in an Indy car becomes an integral part of the chassis: It is the rear spine of the car. The front of an Indy car chassis is a strong and light carbon-fiber tub, providing the structure for the car and the safety capsule for the driver. Behind the fuel tank is a firewall for safety, and the engine is mounted behind it. The gearbox assembly (which includes the rear suspension, both axles and wheels, and the rear wing) is attached directly to the engine. So the engine not only powers the car, but as an integral part of the chassis, it must also have the rigidity to withstand immense forces from these attached components.

With top speeds over 230 miles per hour at Indy, the engine must also fit into the critical aerodynamic design of the entire car. It must be as light and compact as possible, with a very low center of gravity. While the “regular” engine was 161.7 cubic inches, the pushrod engine would be 209 cubic inches. To fit it into the same space would be like forcing thirty-seven gallons of fuel into a thirty-gallon tank.

“Obviously that commitment made it quite challenging,” Illien said. “Because when I really got down to it, it was not straightforward how to package everything in that space. The length was the biggest issue. I really struggled to get it . . . because it was a bigger engine. That was the biggest challenge I had: the packaging.”

Illien sat at his drawing board, pencil in hand, to determine things like the ideal bore and stroke, the V-angle for the cylinders, and the overall size of the engine. Illien worked purely by hand as computer-aided design (CAD) was in its infancy in 1993. (In the hands of several of Ilmor’s designers CAD became essential later in the design process.)

“The major parameters I set down,” Illien said. “I made some schemes on my drawing board so they were very defined and very clear. There was not much freedom because time was the other issue. We just had to go and move forward.”

Mario Illien was born in Chur, Switzerland, in August 1949. Alpine skiing was the preeminent sport in the small town surrounded by the Alps and adjacent to the Rhine River. His home country banned all motorsports activity in 1955 following the most horrendous auto-racing crash ever at LeMans, France, where eighty-three people were killed. Illien’s family didn’t even own an automobile. In Chur, walking or skiing was the preferred method of transportation.

“I don’t know what really sparked [my passion],” said Illien. “But from a very early age I was interested in motorcars and engines. We would play games behind walls and when cars would go by, we would try to recognize the car and model from the sound of the engine. I just was fascinated by cars, particularly the engines. I don’t think it was the fact that we didn’t have a car—there wasn’t any car around to try things on—but I was fascinated by it.”

As a teenager, his reading gravitated toward racing, especially Formula 1.

“I was interested in it, something I had a passion for,” he said. “I didn’t know how I’d get into it ultimately, but there was definitely a desire to do so.”

Illien studied as a technical draftsman until his early twenties when he became a mechanic for Swedish-born driver Joakim “Jo” Bonnier, a brainy man who spoke six languages and studied at Oxford before moving to Paris. Bonnier had a lengthy career in Formula 1 and sports cars, and he found a kindred spirit in Illien, who also spoke multiple languages and clearly possessed an immense intellect.

Sadly, Bonnier was killed in a crash at LeMans in 1972, and the young Illien was forced to move on. He designed a Chrysler Simca Formula 2 engine and another for a motorcycle sidecar racer before he graduated from the Biel University Engineering School in Switzerland with a degree in mechanical engineering in 1976.

After several years designing diesel engines in Switzerland, Illien joined Cosworth Engineering in Northamptonshire, England. Formed by Mike Costin and Keith Duckworth in 1958, Cosworth is one of the top Formula 1 engine companies in history, ranking second only to Ferrari in all-time victories. Debuting in 1966, the Cosworth DFV (Double Four Valve) engine, backed by Ford Motor Company, ruled Formula 1 for nearly fifteen years. Illien initially joined Cosworth to design the evolutionary DFY Formula 1 engine, and also worked on the Indy car engine known as the DFX.

Illien became close friends with another engineer who had been with Cosworth since 1970, a man named Paul Morgan, who was working on the company’s Indy car program.

Why was their friendship and work combination so potent?

“To be engineers and to be able to discuss things and at the same time complement each other in many, many ways,” Illien said. “I think that’s what made it possible.”

The two engineers realized Cosworth’s Indy car engine was not being properly developed. Yet, because of their almost complete monopoly on the CART series, Cosworth wasn’t particularly interested in spending the money to make the improvements proposed by the two engineers.

Convinced they could do better, the two conceived their own Indy car-engine design company. Both were mature enough to handle a new business, but still young and energetic enough to make it work.

“We had worked together on things at Cosworth,” said Illien. “I drew many things for the Cosworth engines and he had them made. We also made a Norton motorcycle engine. Somebody bought that thing and wanted fuel injection and more power to go racing so that became our project. We had a lot of interesting projects together and we knew we could work together. That was the start.”

They had the ideas but lacked a financial backer. In Morgan’s time with the Indy car series in America, he had developed a friendly relationship with Roger Penske, so Morgan called Penske to gauge his interest. When Penske asked for further details, Morgan and Illien, along with their wives, Liz and Catherine, began preparing a document with estimated expenses to create the facility, as well as a timeline to design and build a racing engine for the 1986 season.

From the living room of the Morgan home in Brixworth, the four created a thirty-page handwritten document for Penske. As no copier was available, they took photographs of each page to serve as their record of the proposal. On October 13, 1983, they sent it to Penske via FedEx despite their concern at the considerable expense of paying for an overnight letter out of their own pockets.

In the 1999 book Ilmor: The First 15 Years (printed by Ilmor solely for their employees and corporate sponsors), Illien described the process with Penske, as “a telephone call, a meeting and a handshake. And off we went!”

It wasn’t quite that simple. Penske wanted a fifty percent stake in the company with Illien and Morgan each getting twenty-five percent. Though they initially balked, the pair eventually agreed to sign the contract with Penske on November 22, 1983. Even though their duties would always overlap, Penske defined everyone’s role to make it easier for most to understand: Illien was chief designer, while Morgan was in charge of vendors and manufacturing. Penske was responsible for finding a benefactor for the company.

“Those were the three main goals: running the business, designing the engine and developing an association with a world-class manufacturer,” Penske said in the same Ilmor history book.

Penske eventually interested General Motors and its Chevrolet brand, arguing that a partnership with an Indy car program could help Chevrolet showcase innovation and performance.

The first meeting of GM, Penske, and Ilmor took place in the Morgan home, known as The Brown House, despite Liz Morgan’s horror at not having a “proper” kitchen. Regardless of her worries, the meeting went well. A second meeting was set for October 12, 1984, in Detroit. The lawyers had prepared all the documents and contracts with that date, but the meeting didn’t begin until evening. With the final details to be worked out, tension began to build as midnight neared.

Paul Morgan solved the time problem a few minutes before midnight by reaching for the clock in the room and removing the batteries. Now they could work all night and it would still be October 12! Around four o’clock in the morning, the documents were signed.

General Motors had taken an extraordinary risk, trusting Penske enough to become a partner in a new design company located in the midlands of England. In return, GM received a twenty-five percent share of the company, taken from Penske’s allotment.

The Chevrolet Indy V8/A engine roared to life on the new dyno at Ilmor in May 1985. In August of that year, Rick Mears was the first to drive a Penske chassis with Ilmor power. Mears was not only a championship racer, he was one of the best test drivers, able to assess a chassis and engine very quickly. When Mears put his right foot down, he instantly knew the engine was a winner.

While the early days were fraught with reliability issues between the Ilmor engine and Penske chassis, the engine made its racing debut at Phoenix on April 6, 1986. Al Unser Sr. qualified seventh, but the start of the race proved inauspicious. The engine wouldn’t fire. Finally a dead battery was replaced and Unser joined the fray four laps late. Before retiring from the race due to a crash, Unser ran a number of laps quicker than the race leaders, serving notice that a new contender had arrived in Indy car racing.

For the full story, check out Beast here, and learn how the intrigue, engineering, and utter audacity of three men turned the racing world upside down.

Previous Chapter-Next Chapter