Beast Five: Fractures

Chapter 5 from Beast by Jade Gurss

To celebrate the release of the revised, second edition, Octane Press is releasing excerpts from the award-winning book Beast: The Top Secret Ilmor Penske Engine that Shocked the Racing World at the Indy 500.

Join our mailing list for specials on the second edition and learn how the intrigue, engineering, and utter audacity of three men turned the racing world upside down. Limited quantities of first edition available.

BEAST: CHAPTER FIVE

It's Been Said

“There is no terrible way to win. There is only winning.”

— Dialogue from Grand Prix (1966), directed by John Frankenheimer

One of Tony Hulman’s legacies was the organization he created in 1956 to sanction the 500. The United States Auto Club (USAC, pronounced “U-Sack”) created and enforced rules for the Speedway and the USAC National Championship, a series of races to determine each year’s champion. By the late 1970s, all the races other than the 500 were money losers for team owners, even the winning teams. USAC’s world began and ended at the corner of 16th Street and Georgetown Road in Speedway, Indiana.

In 1978, the year after Hulman’s death, Dan Gurney, one of America’s smartest racers with a multifaceted career as driver, car designer, manufacturer, and team owner (he’s the only American to win a Formula 1 race driving a car of his own design and construction), wrote an influential white paper listing the reasons why all parties could benefit from a race series with better organization and promotion. Bigger attendance and an improved TV package would make major sponsors more likely. (The national TV broadcast of the 500 was not aired live and unedited until 1986!) Gurney’s paper urged marketing and operating the series at a much higher level, emulating other major sports properties and striving to maximize the series’ year-round impact.

After the Speedway and USAC refused to entertain Gurney’s rational thoughts, the team owners (led by Penske, Gurney, and Pat Patrick) formed their own Indy car series and sanctioning body: Championship Auto Racing Teams (CART). The CART board of directors had twenty-four members, with each team owner getting one seat at the table. This proved unruly with two dozen alpha males in the room, but they were now able to make decisions for the long-term good of their teams and the series. The CART Series was launched in 1979 with thirteen races at six tracks (the tracks also had to choose sides). All the big-name teams and drivers went with CART except for A. J. Foyt, who initially joined but returned to USAC three month later out of frustration with the other owners and loyalty to the Hulman family.

“USAC was a bunch of guys who really didn’t understand racing, especially the board of directors,” explained Robin Miller, a journalist who has covered Indy cars for decades. “It was twenty-four guys and half of ’em never saw a race more than once a year.

“USAC had no vision, no brains, no ability to market, and an amazing arrogance. ‘We’re USAC, you come to us. We might deal with you.’ So, USAC deserved to have the Indy car series taken away from them,” Miller concluded.

USAC continued its own championship, and Foyt easily won five of the seven races. Most of his opponents were known for their prowess on regional dirt tracks, driving midgets, sprint cars, and dirt champ cars rather than Indy cars.

Historically the 500 had welcomed the best and brightest from around the world, but now it was “invitation only” for the first time in 1979. In late April, only days before practice for the race was scheduled to begin, USAC’s board chose to punish the CART teams, unanimously voting to exclude many of them from the race. The entry forms for Penske, Patrick, McLaren, Gurney, Jim Hall’s Chaparral team, and other CART participants were rejected for actions deemed “harmful to racing” and were judged “not in good standing” with USAC. If the ban stood, finding replacement cars and drivers to enter the race would be difficult, and filling the stands with angry fans would not be pleasant. Big names and fan favorites such as Al and Bobby Unser, Tom Sneva, Johnny Rutherford, and Gordon Johncock, all previous winners, plus young guns like Rick Mears would not appear.

The CART owners filed a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for southern Indiana, basing their claim on elements such as restraint of trade and antitrust laws. It wasn’t until the first day of practice, Saturday, May 5, that Judge James Ellsworth Nolan granted an injunction in favor of the CART teams. In the race, Mears, with his unique background in off-road desert racing, grabbed the first of his four 500 wins for Team Penske in just his second start at the Brickyard. It was a changing of the guard—Mears was the first winner born after World War II.

The following year, the CART schedule became the true national championship. Its rulebook mostly coincided with USAC’s, which meant the teams ran the 500 with the same equipment they raced year-round. But, like two sports leagues playing the same game with slightly different rules, the Speedway still maintained their additional “equivalency formula” rules for the 500.

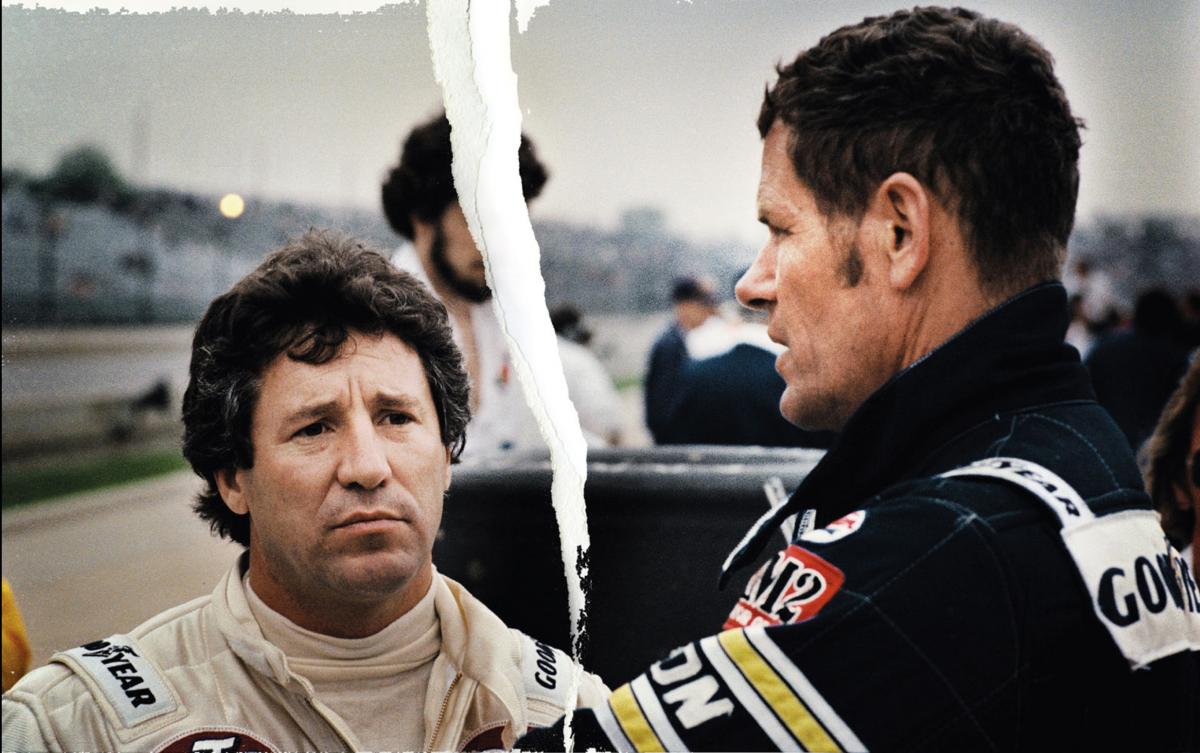

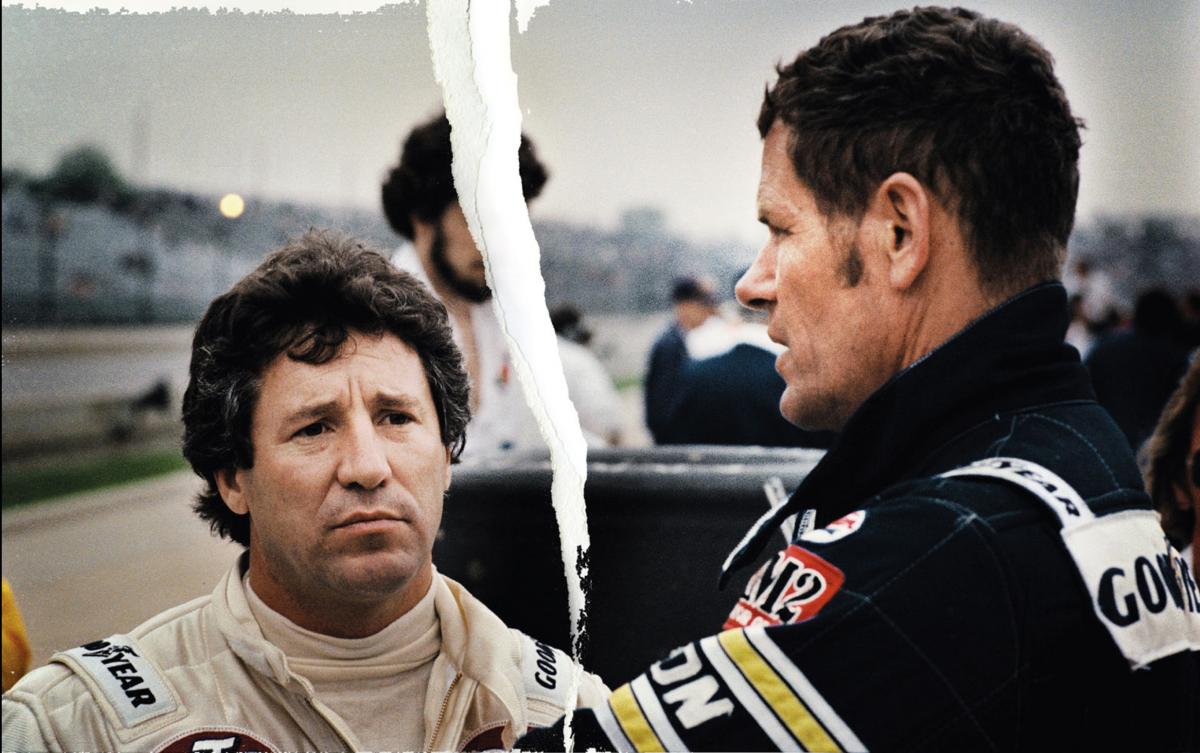

An undercurrent of mistrust continued to percolate, and the 1981 race was the most blatant in a series of strange decisions. Bobby Unser took the checkered flag for Team Penske and celebrated in Victory Lane. The following morning, when the official results were posted, Mario Andretti was named the winner. Overnight, it was decided Unser would be penalized for illegally passing cars during a caution flag period. Although Andretti had done the same, he was not penalized and was declared victor. The battle of lawsuits began, stretching until October 9, when Unser’s win was legally restored. To the outside world, it looked as if the Indy car chaos swirled around petulant children, fighting and stomping their feet. From the inside, it looked much the same.

With star drivers and the best teams, CART saw continued growth through the 1980s and early ’90s, as events like the Long Beach Grand Prix added glamour and profit while sponsorships and TV ratings grew.

A big part of CART’s appeal was the variety of tracks where they raced, which added prestige to the championship.The series raced on short ovals (mostly one-mile in length at places like Phoenix and Milwaukee), superspeedways (two miles and more, such as Indy and Michigan), natural-terrain road courses (such as Road America in Wisconsin, and the Mid-Ohio Sports Car Course), and street circuits (through the city streets of Long Beach and Surfers Paradise in Australia). Variety meant the championship-winning team and driver had proven their skills on a much more diverse schedule of circuits than any other racing series in the world.

“CART evolved into the best series on the planet by 1993,” said Robin Miller. “They had Nigel Mansell, the reigning F1 champ. He left Formula 1 for CART. Bernie [Ecclestone, Formula 1 impresario] almost fainted. We had better TV ratings in Australia, Great Britain, and Brazil than F1 in the early ’90s. CART managed to be on top of the racing world in spite of itself. That’s the best way to describe that era. In spite of the owners’ greed and shortsightedness, they stumbled into this phenomenal series that attracted the world driving champion and had the biggest crowds and the biggest ratings.”

Hard to imagine today, as NASCAR has held the vast majority of American fans, ratings, and sponsor dollars for over fifteen years, but CART matched the popularity of stock cars at that time.

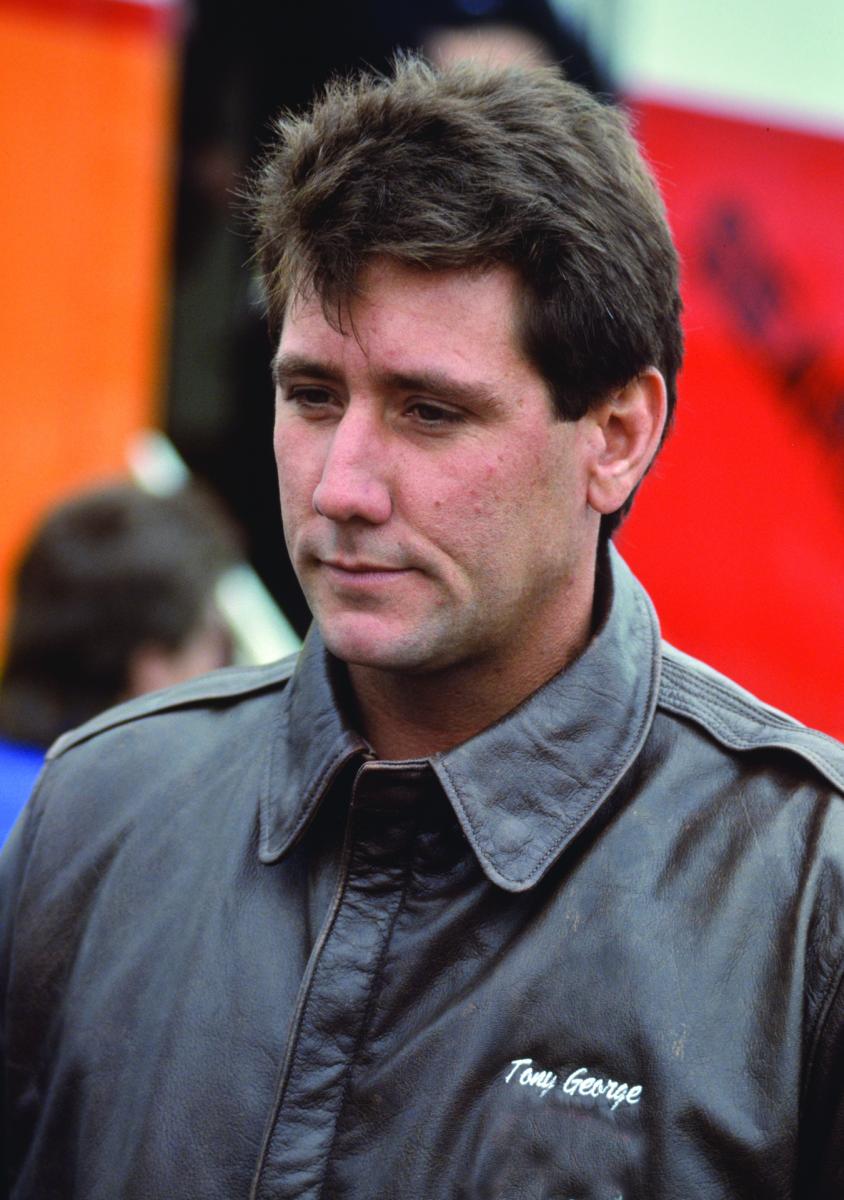

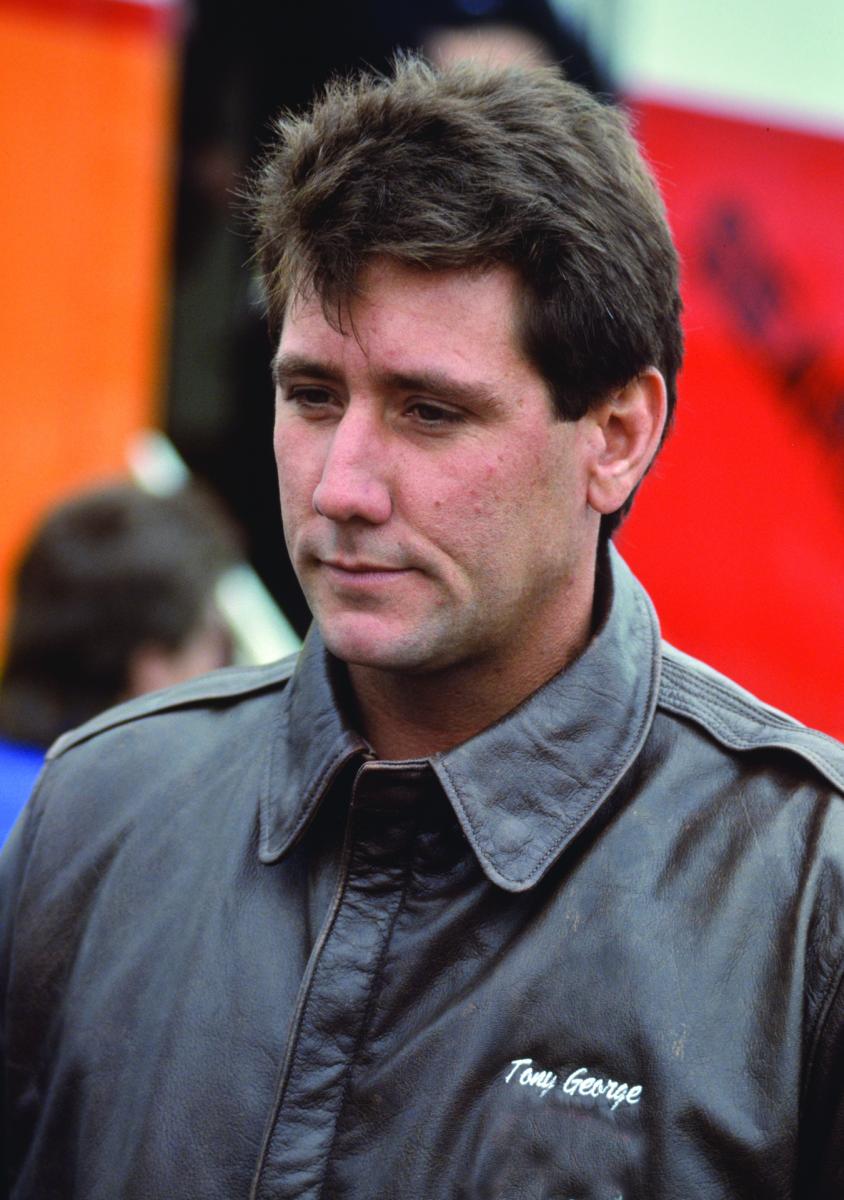

The rift between CART and the Speedway had only deepened when Tony George, a very quiet young man, followed in his grandfather’s footsteps by taking over IMS leadership. Peace offerings were made, including adding George as a CART board member, but each led to a dead end. In 1991, George and his lawyers attended a board meeting and offered to buy the entire series for $1 million. When he was asked to leave, George reportedly decided his next move would be to hold a NASCAR race at the Speedway. He expected it to provide a huge influx of cash for his family, give him more leverage with CART, and provide funds for his long-term plans. In spring 1993, George and NASCAR leader Bill France Jr. announced the Winston Cup Series’ Brickyard 400 would take place in August 1994. Despite cries from traditionalists, the Indy 500 would no longer be the only race held at the hallowed grounds.

One thing that most upset George was the influence held by the engine manufacturers. Cosworth had been dominant for years, until Ilmor appeared with their Chevrolet-branded engine, which had won six consecutive races at the Brickyard since 1988. Each manufacturer had season-long engine deals with a number of CART teams. Most of the smaller teams that raced only at the 500 looked to Buick as an alternative, though Ilmor and Cosworth also did Indy-only deals.

Ilmor’s handiwork first appeared at the Speedway in 1986, powering a single car entered by Penske for Al Unser Sr. The next year, the ranks included two Penske entries as well as top teams such as Newman/Haas and Pat Patrick Racing. By 1988, it was the all-conquering engine, taking the entire front row with Team Penske and sweeping the top-three finishing positions, but it was still available only to four teams. The engines became so prominent that teams without them lobbied to force Ilmor to sell four engines to every team in the field.

Ilmor’s decision to supply a small number of teams was purely a function of their limited size as a new manufacturing company. They were also beginning to develop engines for Formula 1, which stretched their capacity further. Ilmor could not match the manufacturing capacity and corporate financing of decades-old Cosworth. As seasons progressed, their capabilities increased, which allowed more teams to use the engines. They maintained strict criteria whereby a full-season team was required to commit to a minimum of seven engines and agree to a two-year deal. It was pricey and not every team could afford it, but it was the only deal that made sense for Ilmor.

As manufacturers like Porsche joined the series, the competition became more acute. Cosworth, long associated with Ford, reunited with the American automotive giant, and the Italian manufacturer Alfa Romeo entered a one-car effort in 1989. Initially, Ilmor’s contracts with the teams included a clause giving Ilmor first right of refusal to buy back the engines and thus protect its intellectual property.

Pat Patrick, winner of the 1989 Indy 500 and CART championship with driver Emerson Fittipaldi, had decided to retire and sold his team to a former Indy car driver from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, named Chip Ganassi. Yet, after the season, Patrick refused to sell his engines back to Ilmor, raising suspicions. Secretly, Patrick had undergone a change of heart when Alfa Romeo asked him to build a new flagship team for its engine. It soon became clear that Patrick had shipped the engines to Italy for Alfa Romeo to reverse-engineer. They were returned to Ilmor in a sorry state of reassembly. (Justice was served when Alfa failed to score a podium finish in three seasons.)

“The Alfa Romeo incident galvanized everyone’s way of thinking. You’ve got to protect your intellectual property,” explained Paul Ray, president of Ilmor Engineering Inc., the company’s U.S. division. “It was when we decided to really clamp down on bad behavior, and it was then we moved into the leasing world. It was the only way we could protect ourselves from things like that happening again. We owned the intellectual property in the engines, so teams would only pay for the value of the actual parts. The team never took ownership. The leased engines must also be worked on only by an approved service center, which in our case was VDS Racing [in Midland, Texas] and Penske. No one else was allowed to open the engines.”

Mike Devin, a well-respected man with decades in the sport, first as a mechanic, then progressing to chief mechanic and team owner, was hired as USAC’s technical director in 1991. His role was to create and enforce the rulebook for the 500, but emotions and politics from above sometimes interjected.

“There was a little bit of a whizzing contest between the Speedway and CART,” Devin explained with understatement. “CART had control of the engines. The big teams with the big money owned the big leases with both Ilmor and Cosworth, so [Ilmor and Cosworth] were going to do what their major customers do. The onesies and twosies guys at the Speedway were not going to shake and bake any kind of lease under that policy. The [engine manufacturers] followed the CART hard line.”

Devin went on to explain the Speedway’s engine philosophy.

“Myself, Jud Phillips, or Clint Brawner [legendary crew chiefs of the ’60s and ’70s], we were used to [building] our engines in our garage by ourselves,” he said. “You used to have a guy that built his engine in his garage. He’d have an idea then he’d get out his milling machine and turn the handle on it and make something he could bring to the racetrack.

“Then it got to where engineers did these things in a program, and did hours and hours of computer analysis before the first parts were ever made,” Devin said. “It was out of the realm of ‘the common man.’ Then it became ‘Who’s got the most money to throw at whatever platform that they’re interested in? How much engineering and manufacturing wherewithal could you afford to throw at the thing?’ And whoever had the most would take that program forward. That’s when it got difficult. That’s when it wasn’t just mano y mano, it was dollar versus dollar. It was a different thing and it was a foreign technology.”

The thought of an engine built by a grease-covered mechanic in the neighborhood garage was a romantic notion, but not feasible for long-term marketing. Chevrolet (Ilmor-built) and Ford (Cosworth-built) spent vast amounts of marketing dollars on the sport year-round. With only backyard mechanics, who would replace the major manufacturers?

Chevrolet had been putting up billboards around Indianapolis proclaiming, “You can’t win Indy without one.” Since no one could buy an Ilmor/Chevy engine off the shelf, it increasingly upset George to have a CART-derived engine dominating his race. His frustration became anger after an incident that took place ten days before the 1991 race.

“Al Unser Sr. was without a ride at the Speedway, and [team owner Vince] Granatelli wanted to put him into a second car,” Devin said, explaining George’s perception of the situation. “Ilmor wouldn’t allow him to have an engine. That pissed Tony off that he couldn’t have one of his champions in the field. [Unser Sr.] was clearly a very popular guy and Ilmor just said ‘No. You can’t do it. We’ve got engines, but we don’t have an engineer we can send down to start it for you. You just can’t enter.’”

The Speedway fanned the controversy, painting Ilmor as villains and acting as if ordering a new racing engine ten days before the race was the same as ordering fast food. Unser Sr., the first driver to start a 500 with Ilmor power, was helped by Chevrolet executives who tried to put a deal together. Granatelli told Chicago Tribune reporter Robert Markus the team couldn’t have a car ready in time. For their part, Ilmor had a very fundamental reason why the deal could not happen.

“We didn’t have an engine! It was that simple,” explained Paul Ray. “Engines were [built for] race teams who signed a lease for a certain number of engines. Those engines were in the possession of the teams. You had to order an engine and we’d build it for you well ahead of time. Ilmor did not own an engine of our own that we could loan to them or lease to them or in some way get to them. With [Al] Senior’s great relationship with Roger Penske, you know damn well that it would have worked out if it could have. It wasn’t like Ilmor had a problem with Senior. Nothing could be further from the truth.”

Tony George believed it was in the best interest of the Speedway to have an engine available to all teams at a low cost to prevent this sort of situation. And it could not be a CART engine—hence, meetings with General Motors that led USAC to remove the words “stock block” from the rulebook.

“The Speedway would come to us with any policy changes,” Devin said of USAC’s role. “They would explain to us what they wanted. Sometimes we agreed, sometimes we didn’t. But if they wanted it, it happened. They were the tail that wagged the dog. . . . At USAC, we made all the rules, but we never published a rule without bringing it to the Speedway and explaining its ramifications. We couldn’t let the Speedway get blindsided.

“The Speedway didn’t necessarily need USAC,” Devin continued. “Especially when it was only the one race, but they didn’t want to take the responsibility. If anything happened, they wanted a buffer zone. And USAC was their buffer zone. We were the ones you could blame and we would never say anything. That was our station in life. We had a good gig and we were paid well to do it. A lot of times you had to hold your tongue.”

According to Devin, George’s anger was brought to a boil a second time in a CART board meeting two years later. CART’s business plan was much like those of other major sports leagues like the National Football League and Major League Baseball. By consolidating all prize money and income, the league was able to distribute the money among all teams. In an audacious move, CART management asked if the Speedway would entertain the idea of providing the prize money directly to the league in advance rather than to the teams after the 500. In return, CART teams would agree to enter enough cars to fill the field.

It was an offensive idea to George, who wanted to maintain the Speedway’s leverage and to prevent the smaller Indy-only teams from being shut out. Devin, who attended the board meeting with George, explained how the conversation developed.

“I’m not going to do that,” George said. “I’m not going to send you guys the money.”

George’s quiet personality often infuriated the others. He rarely spoke in the meetings, but would then complain afterward. After more discussion, a single rhetorical question was the tipping point.

“Well, Tony, what would happen if we decide not to come?” asked CART president Bill Stokkan, according to Devin’s account of the meeting. Immediately, both Penske and Carl Haas stood up to insist that was absolutely not their intention.

“Tony looked around and said, ‘It’s been said,’” Devin recounted. “He got up from the table and looked at me and said, ‘Let’s go. It’s been said.’ Tony was fuming. ‘If they brought it up, obviously it’s something they have been thinking about.’”

Once aboard his private jet, George poured shots of scotch for Devin and himself.

“We’ve got to do something about that. Nobody has ever said that before,” George said to Devin. “You can’t put it back in the bag, it’s been said. We’ve got to do something.”

That “something” would cripple open-wheel racing in America—perhaps forever.

For the full story, check out Beast here, and learn how the intrigue, engineering, and utter audacity of three men turned the racing world upside down.

Previous Chapter-Next Chapter

Join our mailing list for specials on the second edition and learn how the intrigue, engineering, and utter audacity of three men turned the racing world upside down. Limited quantities of first edition available.

BEAST: CHAPTER FIVE

It's Been Said

“There is no terrible way to win. There is only winning.”

— Dialogue from Grand Prix (1966), directed by John Frankenheimer

One of Tony Hulman’s legacies was the organization he created in 1956 to sanction the 500. The United States Auto Club (USAC, pronounced “U-Sack”) created and enforced rules for the Speedway and the USAC National Championship, a series of races to determine each year’s champion. By the late 1970s, all the races other than the 500 were money losers for team owners, even the winning teams. USAC’s world began and ended at the corner of 16th Street and Georgetown Road in Speedway, Indiana.

In 1978, the year after Hulman’s death, Dan Gurney, one of America’s smartest racers with a multifaceted career as driver, car designer, manufacturer, and team owner (he’s the only American to win a Formula 1 race driving a car of his own design and construction), wrote an influential white paper listing the reasons why all parties could benefit from a race series with better organization and promotion. Bigger attendance and an improved TV package would make major sponsors more likely. (The national TV broadcast of the 500 was not aired live and unedited until 1986!) Gurney’s paper urged marketing and operating the series at a much higher level, emulating other major sports properties and striving to maximize the series’ year-round impact.

After the Speedway and USAC refused to entertain Gurney’s rational thoughts, the team owners (led by Penske, Gurney, and Pat Patrick) formed their own Indy car series and sanctioning body: Championship Auto Racing Teams (CART). The CART board of directors had twenty-four members, with each team owner getting one seat at the table. This proved unruly with two dozen alpha males in the room, but they were now able to make decisions for the long-term good of their teams and the series. The CART Series was launched in 1979 with thirteen races at six tracks (the tracks also had to choose sides). All the big-name teams and drivers went with CART except for A. J. Foyt, who initially joined but returned to USAC three month later out of frustration with the other owners and loyalty to the Hulman family.

“USAC was a bunch of guys who really didn’t understand racing, especially the board of directors,” explained Robin Miller, a journalist who has covered Indy cars for decades. “It was twenty-four guys and half of ’em never saw a race more than once a year.

“USAC had no vision, no brains, no ability to market, and an amazing arrogance. ‘We’re USAC, you come to us. We might deal with you.’ So, USAC deserved to have the Indy car series taken away from them,” Miller concluded.

USAC continued its own championship, and Foyt easily won five of the seven races. Most of his opponents were known for their prowess on regional dirt tracks, driving midgets, sprint cars, and dirt champ cars rather than Indy cars.

Historically the 500 had welcomed the best and brightest from around the world, but now it was “invitation only” for the first time in 1979. In late April, only days before practice for the race was scheduled to begin, USAC’s board chose to punish the CART teams, unanimously voting to exclude many of them from the race. The entry forms for Penske, Patrick, McLaren, Gurney, Jim Hall’s Chaparral team, and other CART participants were rejected for actions deemed “harmful to racing” and were judged “not in good standing” with USAC. If the ban stood, finding replacement cars and drivers to enter the race would be difficult, and filling the stands with angry fans would not be pleasant. Big names and fan favorites such as Al and Bobby Unser, Tom Sneva, Johnny Rutherford, and Gordon Johncock, all previous winners, plus young guns like Rick Mears would not appear.

The CART owners filed a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for southern Indiana, basing their claim on elements such as restraint of trade and antitrust laws. It wasn’t until the first day of practice, Saturday, May 5, that Judge James Ellsworth Nolan granted an injunction in favor of the CART teams. In the race, Mears, with his unique background in off-road desert racing, grabbed the first of his four 500 wins for Team Penske in just his second start at the Brickyard. It was a changing of the guard—Mears was the first winner born after World War II.

The following year, the CART schedule became the true national championship. Its rulebook mostly coincided with USAC’s, which meant the teams ran the 500 with the same equipment they raced year-round. But, like two sports leagues playing the same game with slightly different rules, the Speedway still maintained their additional “equivalency formula” rules for the 500.

An undercurrent of mistrust continued to percolate, and the 1981 race was the most blatant in a series of strange decisions. Bobby Unser took the checkered flag for Team Penske and celebrated in Victory Lane. The following morning, when the official results were posted, Mario Andretti was named the winner. Overnight, it was decided Unser would be penalized for illegally passing cars during a caution flag period. Although Andretti had done the same, he was not penalized and was declared victor. The battle of lawsuits began, stretching until October 9, when Unser’s win was legally restored. To the outside world, it looked as if the Indy car chaos swirled around petulant children, fighting and stomping their feet. From the inside, it looked much the same.

With star drivers and the best teams, CART saw continued growth through the 1980s and early ’90s, as events like the Long Beach Grand Prix added glamour and profit while sponsorships and TV ratings grew.

A big part of CART’s appeal was the variety of tracks where they raced, which added prestige to the championship.The series raced on short ovals (mostly one-mile in length at places like Phoenix and Milwaukee), superspeedways (two miles and more, such as Indy and Michigan), natural-terrain road courses (such as Road America in Wisconsin, and the Mid-Ohio Sports Car Course), and street circuits (through the city streets of Long Beach and Surfers Paradise in Australia). Variety meant the championship-winning team and driver had proven their skills on a much more diverse schedule of circuits than any other racing series in the world.

“CART evolved into the best series on the planet by 1993,” said Robin Miller. “They had Nigel Mansell, the reigning F1 champ. He left Formula 1 for CART. Bernie [Ecclestone, Formula 1 impresario] almost fainted. We had better TV ratings in Australia, Great Britain, and Brazil than F1 in the early ’90s. CART managed to be on top of the racing world in spite of itself. That’s the best way to describe that era. In spite of the owners’ greed and shortsightedness, they stumbled into this phenomenal series that attracted the world driving champion and had the biggest crowds and the biggest ratings.”

Hard to imagine today, as NASCAR has held the vast majority of American fans, ratings, and sponsor dollars for over fifteen years, but CART matched the popularity of stock cars at that time.

The rift between CART and the Speedway had only deepened when Tony George, a very quiet young man, followed in his grandfather’s footsteps by taking over IMS leadership. Peace offerings were made, including adding George as a CART board member, but each led to a dead end. In 1991, George and his lawyers attended a board meeting and offered to buy the entire series for $1 million. When he was asked to leave, George reportedly decided his next move would be to hold a NASCAR race at the Speedway. He expected it to provide a huge influx of cash for his family, give him more leverage with CART, and provide funds for his long-term plans. In spring 1993, George and NASCAR leader Bill France Jr. announced the Winston Cup Series’ Brickyard 400 would take place in August 1994. Despite cries from traditionalists, the Indy 500 would no longer be the only race held at the hallowed grounds.

One thing that most upset George was the influence held by the engine manufacturers. Cosworth had been dominant for years, until Ilmor appeared with their Chevrolet-branded engine, which had won six consecutive races at the Brickyard since 1988. Each manufacturer had season-long engine deals with a number of CART teams. Most of the smaller teams that raced only at the 500 looked to Buick as an alternative, though Ilmor and Cosworth also did Indy-only deals.

Ilmor’s handiwork first appeared at the Speedway in 1986, powering a single car entered by Penske for Al Unser Sr. The next year, the ranks included two Penske entries as well as top teams such as Newman/Haas and Pat Patrick Racing. By 1988, it was the all-conquering engine, taking the entire front row with Team Penske and sweeping the top-three finishing positions, but it was still available only to four teams. The engines became so prominent that teams without them lobbied to force Ilmor to sell four engines to every team in the field.

Ilmor’s decision to supply a small number of teams was purely a function of their limited size as a new manufacturing company. They were also beginning to develop engines for Formula 1, which stretched their capacity further. Ilmor could not match the manufacturing capacity and corporate financing of decades-old Cosworth. As seasons progressed, their capabilities increased, which allowed more teams to use the engines. They maintained strict criteria whereby a full-season team was required to commit to a minimum of seven engines and agree to a two-year deal. It was pricey and not every team could afford it, but it was the only deal that made sense for Ilmor.

As manufacturers like Porsche joined the series, the competition became more acute. Cosworth, long associated with Ford, reunited with the American automotive giant, and the Italian manufacturer Alfa Romeo entered a one-car effort in 1989. Initially, Ilmor’s contracts with the teams included a clause giving Ilmor first right of refusal to buy back the engines and thus protect its intellectual property.

Pat Patrick, winner of the 1989 Indy 500 and CART championship with driver Emerson Fittipaldi, had decided to retire and sold his team to a former Indy car driver from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, named Chip Ganassi. Yet, after the season, Patrick refused to sell his engines back to Ilmor, raising suspicions. Secretly, Patrick had undergone a change of heart when Alfa Romeo asked him to build a new flagship team for its engine. It soon became clear that Patrick had shipped the engines to Italy for Alfa Romeo to reverse-engineer. They were returned to Ilmor in a sorry state of reassembly. (Justice was served when Alfa failed to score a podium finish in three seasons.)

“The Alfa Romeo incident galvanized everyone’s way of thinking. You’ve got to protect your intellectual property,” explained Paul Ray, president of Ilmor Engineering Inc., the company’s U.S. division. “It was when we decided to really clamp down on bad behavior, and it was then we moved into the leasing world. It was the only way we could protect ourselves from things like that happening again. We owned the intellectual property in the engines, so teams would only pay for the value of the actual parts. The team never took ownership. The leased engines must also be worked on only by an approved service center, which in our case was VDS Racing [in Midland, Texas] and Penske. No one else was allowed to open the engines.”

Mike Devin, a well-respected man with decades in the sport, first as a mechanic, then progressing to chief mechanic and team owner, was hired as USAC’s technical director in 1991. His role was to create and enforce the rulebook for the 500, but emotions and politics from above sometimes interjected.

“There was a little bit of a whizzing contest between the Speedway and CART,” Devin explained with understatement. “CART had control of the engines. The big teams with the big money owned the big leases with both Ilmor and Cosworth, so [Ilmor and Cosworth] were going to do what their major customers do. The onesies and twosies guys at the Speedway were not going to shake and bake any kind of lease under that policy. The [engine manufacturers] followed the CART hard line.”

Devin went on to explain the Speedway’s engine philosophy.

“Myself, Jud Phillips, or Clint Brawner [legendary crew chiefs of the ’60s and ’70s], we were used to [building] our engines in our garage by ourselves,” he said. “You used to have a guy that built his engine in his garage. He’d have an idea then he’d get out his milling machine and turn the handle on it and make something he could bring to the racetrack.

“Then it got to where engineers did these things in a program, and did hours and hours of computer analysis before the first parts were ever made,” Devin said. “It was out of the realm of ‘the common man.’ Then it became ‘Who’s got the most money to throw at whatever platform that they’re interested in? How much engineering and manufacturing wherewithal could you afford to throw at the thing?’ And whoever had the most would take that program forward. That’s when it got difficult. That’s when it wasn’t just mano y mano, it was dollar versus dollar. It was a different thing and it was a foreign technology.”

The thought of an engine built by a grease-covered mechanic in the neighborhood garage was a romantic notion, but not feasible for long-term marketing. Chevrolet (Ilmor-built) and Ford (Cosworth-built) spent vast amounts of marketing dollars on the sport year-round. With only backyard mechanics, who would replace the major manufacturers?

Chevrolet had been putting up billboards around Indianapolis proclaiming, “You can’t win Indy without one.” Since no one could buy an Ilmor/Chevy engine off the shelf, it increasingly upset George to have a CART-derived engine dominating his race. His frustration became anger after an incident that took place ten days before the 1991 race.

“Al Unser Sr. was without a ride at the Speedway, and [team owner Vince] Granatelli wanted to put him into a second car,” Devin said, explaining George’s perception of the situation. “Ilmor wouldn’t allow him to have an engine. That pissed Tony off that he couldn’t have one of his champions in the field. [Unser Sr.] was clearly a very popular guy and Ilmor just said ‘No. You can’t do it. We’ve got engines, but we don’t have an engineer we can send down to start it for you. You just can’t enter.’”

The Speedway fanned the controversy, painting Ilmor as villains and acting as if ordering a new racing engine ten days before the race was the same as ordering fast food. Unser Sr., the first driver to start a 500 with Ilmor power, was helped by Chevrolet executives who tried to put a deal together. Granatelli told Chicago Tribune reporter Robert Markus the team couldn’t have a car ready in time. For their part, Ilmor had a very fundamental reason why the deal could not happen.

“We didn’t have an engine! It was that simple,” explained Paul Ray. “Engines were [built for] race teams who signed a lease for a certain number of engines. Those engines were in the possession of the teams. You had to order an engine and we’d build it for you well ahead of time. Ilmor did not own an engine of our own that we could loan to them or lease to them or in some way get to them. With [Al] Senior’s great relationship with Roger Penske, you know damn well that it would have worked out if it could have. It wasn’t like Ilmor had a problem with Senior. Nothing could be further from the truth.”

Tony George believed it was in the best interest of the Speedway to have an engine available to all teams at a low cost to prevent this sort of situation. And it could not be a CART engine—hence, meetings with General Motors that led USAC to remove the words “stock block” from the rulebook.

“The Speedway would come to us with any policy changes,” Devin said of USAC’s role. “They would explain to us what they wanted. Sometimes we agreed, sometimes we didn’t. But if they wanted it, it happened. They were the tail that wagged the dog. . . . At USAC, we made all the rules, but we never published a rule without bringing it to the Speedway and explaining its ramifications. We couldn’t let the Speedway get blindsided.

“The Speedway didn’t necessarily need USAC,” Devin continued. “Especially when it was only the one race, but they didn’t want to take the responsibility. If anything happened, they wanted a buffer zone. And USAC was their buffer zone. We were the ones you could blame and we would never say anything. That was our station in life. We had a good gig and we were paid well to do it. A lot of times you had to hold your tongue.”

According to Devin, George’s anger was brought to a boil a second time in a CART board meeting two years later. CART’s business plan was much like those of other major sports leagues like the National Football League and Major League Baseball. By consolidating all prize money and income, the league was able to distribute the money among all teams. In an audacious move, CART management asked if the Speedway would entertain the idea of providing the prize money directly to the league in advance rather than to the teams after the 500. In return, CART teams would agree to enter enough cars to fill the field.

It was an offensive idea to George, who wanted to maintain the Speedway’s leverage and to prevent the smaller Indy-only teams from being shut out. Devin, who attended the board meeting with George, explained how the conversation developed.

“I’m not going to do that,” George said. “I’m not going to send you guys the money.”

George’s quiet personality often infuriated the others. He rarely spoke in the meetings, but would then complain afterward. After more discussion, a single rhetorical question was the tipping point.

“Well, Tony, what would happen if we decide not to come?” asked CART president Bill Stokkan, according to Devin’s account of the meeting. Immediately, both Penske and Carl Haas stood up to insist that was absolutely not their intention.

“Tony looked around and said, ‘It’s been said,’” Devin recounted. “He got up from the table and looked at me and said, ‘Let’s go. It’s been said.’ Tony was fuming. ‘If they brought it up, obviously it’s something they have been thinking about.’”

Once aboard his private jet, George poured shots of scotch for Devin and himself.

“We’ve got to do something about that. Nobody has ever said that before,” George said to Devin. “You can’t put it back in the bag, it’s been said. We’ve got to do something.”

That “something” would cripple open-wheel racing in America—perhaps forever.

For the full story, check out Beast here, and learn how the intrigue, engineering, and utter audacity of three men turned the racing world upside down.

Previous Chapter-Next Chapter