Bad Boys of IMSA

This excerpt is from Chapter 10 our award-winning book IMSA: 1969-1989.

It’s no secret racing takes talent and money – lots of it, especially if you want to compete for the top step of the podium. Most of the team owners at the sharp end of the grid in the Camel GT Series made their money by legitimate means and many developed beneficial sponsor deals to support them. But no history of the Camel GT Series would be complete without telling the stories of the bad boys of IMSA, the few that made their racing money on the wrong side of the law.

The stories about these outlaws were outrageous and at times hard to believe. The tales about their rise to fame and inevitable falls from grace have taken on a life of their own over the years, both tainting the Camel GT Series and giving it the kind of spice that makes for the stuff of legends. “The running joke in the paddock at the time was that IMSA stood for the International Marijuana Smugglers Association,” recalled Bobby Rahal. The truth was far more mundane; the bulk of Camel GT fields were made up of honest businessmen, but the bad apples stood out and attracted all the wrong kind of salacious media coverage.

John Paul Sr. and his Legendary Temper

The first of these characters was Hans Johan Paul who emigrated from the Netherlands to the U.S. with his parents in 1956. He changed his name to John Paul, married and had a son in 1960 that he also named John. After graduating from Harvard, he became a successful mutual fund manager and began to amass considerable wealth.

John Paul Sr. began his racing career with local SCCA events in the 1960s, winning an SCCA Northeast Regional Championship in 1968. Domestic strife derailed his racing career and estranged him from his son for a few years, but he resumed racing in the early 1970s, entering a Corvette in IMSA races.

The elder Paul shared a Porsche Carrera with John O’Steen and Bob Hagestad at the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1977. He would go on to contest the bulk of that season, sometimes in a Carrera but mostly in a Monza. For the 1978 season, Paul Sr. competed in the latest specification AAGT big-block John Greenwood Corvette, ultimately finishing a credible sixth in the points standings. The next year he upgraded to a Porsche 935 and not only competed in the Camel GT Series, finishing 12th in the points standings, but also won the 1979 SCCA Trans-Am Category II championship in the same car.

It’s not clear how John Paul Sr. got tangled up in the drug trade, but his legal issues began in January 1979 when he was caught with $10,000 cash and more than 1,500 pounds of marijuana in the bayous of Louisiana. Remarkably, he got away with just a fine and three years of probation after pleading guilty to marijuana possession. Not many in the IMSA paddock knew about his brush with the law, but whispers began circulating about the source of the money that supported his increasingly large racing budget. His light blue cars always seemed to be unsponsored, at least until 1982 when Miller beer jumped on in the form of an Atlanta area beer distributor providing support.

The 1980 season turned out to be his best. By this time, John Paul Jr. had begun racing in lower formulas and demonstrated a keen natural talent. Together, father and son won the 1980 Lime Rock Camel GT race. Remarkably, it was the younger Paul’s first-ever IMSA race and the first time he raced the 935. They added a win at Road America and Paul Sr. went on to score another ten Top 5 finishes and ended up second in the Camel GT championship. He also won the 1980 FIA World Challenge for Endurance Drivers, which compiled points from selected long-distance races, five on the IMSA schedule and five FIA events at Monza, Silverstone, Nurburgring, Le Mans and Spa.

Taking advantage of more liberal rules intended to keep the 935 competitive with GTP prototypes, Paul Sr. had a full ground-effects 935 developed for the 1982 season, dubbed the JLP-4 to distinguish it from the older but very successful JLP-3, on which he had also spent an enormous sum. Although the car only faintly resembled the original 935, it was a rocket ship and helped propel John Paul Jr. to the 1982 Camel GT championship. The elder Paul won the Camel Endurance Championship the same year. It was to be the last hurrah for the JLP team.

Out of sight, federal authorities had spent a year carefully building a case against Paul Sr., ultimately indicting him for marijuana smuggling. On April 19, 1983, Stephen Carson, the key federal witness in the case, was shot and nearly killed by Paul Sr. at a marina in Florida. Apparently, Paul Sr. arranged for the late-night meeting and for unknown reasons, Carson agreed to show up. Without his testimony, the federal authorities didn’t have much of a case. The plan backfired when Carson survived the attack. He and a companion both identified Paul Sr. as the shooter and he was quickly arrested. Charged with attempted murder of a federal witness, his legal problems had been significantly compounded.

Then, things got worse; Paul Sr. skipped bail before his scheduled trial in December of 1983. Thirteen months after jumping bail, he was caught living under an assumed name in Switzerland and extradited back to the U.S. On top of pleading guilty in 1986 to attempted murder, he was tried and convicted of tax evasion and drug smuggling charges in 1987. After serving 11 years in prison including one attempted escape, Paul Sr. was paroled in 1999. He was questioned but not detained in the mysterious 2000 disappearance of Colleen Wood, a woman who had joined him for an extended sailing cruise. She has never been found. Paul subsequently disappeared to whereabouts unknown.

John Paul Jr. was an extraordinary talent behind the wheel of a race car and was recognized by team owners such as NASCAR’s Junior Johnson as one of America’s top young drivers. His IMSA success gave him choices. He moved to CART racing in 1983 and in only his fourth start passed Rick Mears on the last lap to win the Michigan 500, justifying predictions of future success. Continuing in IMSA on board the potent Phil Conte-owned RC Cola Buick March, Paul Jr. eventually got caught out by his father’s illegal activities and was indicted while the manhunt for his father was ongoing.

After pleading guilty to federal racketeering charges in 1985, he spent more than two years in prison. Upon his release in 1988, the racing community opened its arms to him. He had done his time, and many felt his father had bullied him into the drug trafficking trade against his will. Paul Jr. resumed his racing career, scoring seven IMSA wins and an Indy Racing League victory at Texas in 1998 – 15 years after that inaugural Indy car win in Michigan. He competed in seven Indy 500s with a best finish of seventh in 1998.

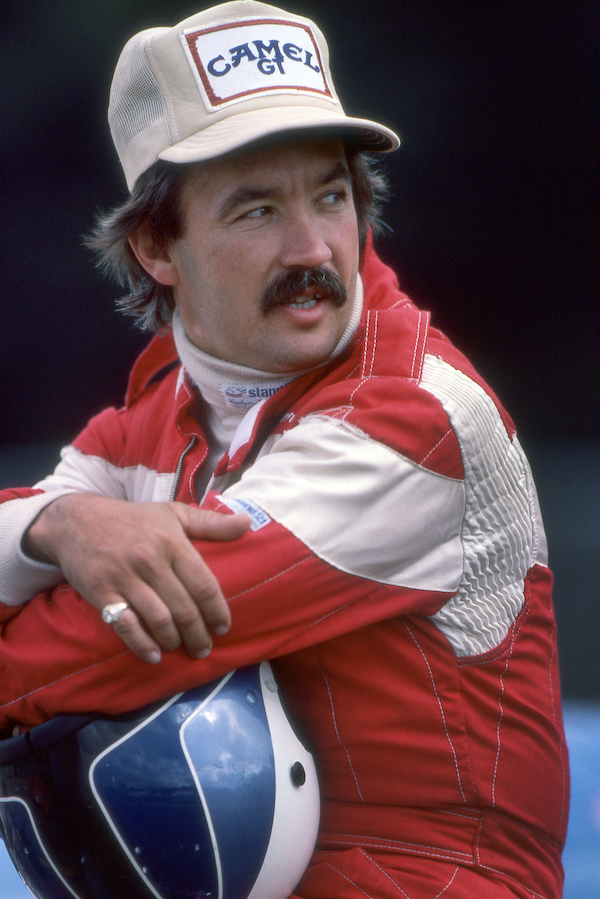

John Paul Sr. relaxes before a Camel GT race. Rob Hermann

As John Paul Sr. became a familiar sight in the IMSA paddock, so did his legendary temper. Check out stories One story as related by Jim Busby: “I had decided to do the 1977 Mid-Ohio race on my own. Most other guys had co-drivers, but I had driven the race alone before and won it. But this time, about three hours into the race, my hands started cramping and I was so hot that I started to hallucinate. I radioed into my crew chief: ‘We need to find a co-driver, fast!’

“As it happened, we were pitted right next to John Paul Sr. My crew chief looked down and John O’Steen, Paul Sr.’s designated co-driver, was suited up, ready to take over. Without telling me anything on the radio, he runs down and convinces him to get in my car instead, explaining all the knobs, buttons, and shift patterns of a 935 to him while they wait for me. “I pit and O’Steen gets in and takes off. After about forty-five minutes of rest in the pits, I cool off enough to resume driving and take it to the end of the race. When I get back to the pits, John Paul Sr. is waiting for me—livid. He’s screaming that he’s going to kill me and shoot my crew. I had no idea what was going on. It was real scary. Yes, we were in the wrong and ruined his race, but I didn’t think it was a crime punishable by death. Like a lot of people, I steered clear of him after that.”

Racing on the Edge: Randy Lanier

Randy Lanier's family moved to Melbourne, Florida when he was a teenager, during a time when television’s Don Johnson and Miami Vice glamorized the South Florida drug scene. The lure of a fast-paced lifestyle impacted young Lanier. More interested in going to the beach with friends or smoking pot than attending classes, he began selling marijuana to high school classmates as a way of earning some quick money and getting to smoke weed for free.

About to be suspended for selling a joint to a classmate, Lanier dropped out of high school and started working construction jobs. But he was soon selling pot to fellow construction workers. The money was good, way better than what he was earning with hard labor. The business escalated and at the age of nineteen, he bought his first speedboat. From there, it was a relatively small jump to ferrying marijuana for the local mob from offshore ships to drop areas on the beach. Over time, the boats became bigger, faster, and more elusive. Before he reached the age of thirty, Lanier found himself in charge of a multi-million dollar trafficking business that was bringing in more than 100,000 pounds of drugs a year directly from Columbia to various ports on the East Coast.

Lanier’s racing career was the definition of meteoric. It started almost by accident when he signed up for lessons at an SCCA booth at a local trade show in the late 1970s. After fixing up a 1957 Porsche 356 in his carport, he raced at SCCA events with enough success to earn himself a spot at the 1980 National Runoffs at Road Atlanta, where he met John Paul Sr. Having started to race relatively late in life, he was making up for lost time.

Lanier’s first contact with IMSA racing happened at the 1981 season finale at Daytona, where he co-drove with Dale Whittington in a 935. Lanier made the rounds of the paddock at Daytona and instantly bonded with the other South Florida guys who were by then a regular part of the IMSA scene: Whittington brothers, Preston Henn, and Marty Hinze.

At the 1982 24 Hours of Daytona, he was pressed into service as a last-minute stand-in for an ailing Janet Guthrie at the wheel of an N.A.R.T. Ferrari 512 BB/LM with Bob Wollek as the lead driver. Lanier crashed the car out of third place during his first stint in the car, eighteen hours into the race.

By March, he was co-driving a 935 with Dale Whittington and Henn in the Sebring 12 Hours. He shared a similar ride with Hinze at Charlotte in May. At the annual Daytona Paul Revere race in July, he finished fourth overall with Henn, followed by a third-place podium with Hinze at Mosport in August. Lanier was building a reputation as a fast driver with means. From out of nowhere, he scored enough points in 1982 to finish sixteenth in the season standings and was invited by Preston Henn to co-drive a Ferrari 512 BB/LM at Le Mans that year. Lanier would finish an impressive second in the 1983 24 Hours of Daytona.

Along with Bill Whittington, Lanier formed Blue Thunder Racing in early 1984. The name of the team was purposeful and pointed to Lanier’s growing recklessness around his business dealings. Blue Thunder referred to a thirty-nine- foot, twin-hulled catamaran designed by Don Aronow, a world champion speedboat pilot and famous designer/builder of high-speed, cigarette-style boats. He sold fourteen Blue Thunder boats to the US Customs Service on the promise they could out-run the single-hull boats smugglers were using, many of which were also designed by Aronow. Turned out, the Blue Thunder boats couldn’t and the government wasted millions on the program.

Years later, Aronow was gunned down in broad daylight on February 3, 1987, in Miami. Almost ten years after the murder, a career criminal named Bobby Young and speed- boat ace Ben Kramer, owner of Apache Powerboats and Lanier’s sponsor during his 1984 Camel GT title run, each pleaded no contest to the killing. Apparently, the shooting was in retaliation for a business deal gone sour, but rumors have since swirled that the real story went deeper. At the time, Kramer was already serving a lengthy prison sentence with a group of inmates that included Lanier.

Helped with setup and coaching by Bill Whittington, and armed with a March 84G-Chevy, Lanier won six races in 1984 and finished in the top five another five times to clinch the Camel GT championship in just his second year of full- time IMSA racing.

Ironically, his quick success sowed the seeds of Lanier’s ultimate downfall. Without visible means of support, little sponsorship, and without the involvement of March Engi- neering, Lanier had somehow pulled off a miracle champi- onship against seemingly better-funded and more skilled competition. Federal authorities, having already been on the trail of the Whittingtons, began investigating.

In 1985, Lanier turned his attention to CART’s Indy cars and entered the Indianapolis 500. He wasn’t allowed to compete by race organizers due to his lack of oval experience, but he returned the next year to obliterate the rookie qualifying record. He started thirteenth, finished tenth, and earned Rookie of the Year honors. But by this time, the Whittingtons were busy dealing with their legal issues and the noose was tightening on Lanier.

Along with ten other people, Lanier was indicted on money laundering and drug trafficking charges in Miami federal court in October 1986, for bringing marijuana into Florida. The organization was estimated to be importing in excess of 300 tons of marijuana every year from Columbia in a sophisticated operation that involved speedboats, barges, tugboats, and trucks. Money from the operation was being laundered through a network of fictitious organizations and international banks. Lanier’s business partners were also indicted: Ben Kramer (who would later confess to the murder of Aronow) and Kramer’s father, Jack. Although recovering from a broken leg sustained in a crash during CART’s five- hundred-mile race in Michigan, Lanier surrendered to authorities and was released on bail.

Lanier’s legal issues worsened in January 1987 when additional federal charges were leveled in Illinois that accused him of being a “drug kingpin” who had smuggled more than 150 tons of marijuana into the country over the previous three years. The operation in Illinois had come unraveled when a state trooper came across a disabled truck on the side of the road that contained a small amount of marijuana. The trail led directly back to Lanier and his partners. Now facing the possibility of significant jail time, he fled the country, only to be recaptured while fishing in Antigua a few months later.

Following a three-month trial in 1988, Lanier was convicted of engaging in a continuing criminal enterprise, conspiracy to distribute more than 1,000 pounds of marijuana, and tax fraud. For these crimes, he was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. The harsh sentence was the result of a 1984 law called the “Super Drug Kingpin” provision of the Continuing Criminal Enterprise Statute, designed to deter others from going into the drug distribution business. After spending twenty-six years in federal prison and without explanation from the government, Lanier was released in October 2014.

The reaction from IMSA to the spate of drug trafficking convictions was predictably subdued. “We felt kind of sick inside,” remembered John Bishop. “We were worried, of course, about the reaction from R. J. Reynolds, but they were pretty mature about it. They’d been through the same kind of thing with some NASCAR teams, so they weren’t exactly innocent about the potential of the problem, but we weathered that together and it wasn’t as traumatic as it could have been.”

Randy Lanier during his 1984 championship winning season. Bob Harmeyer

Randy Lanier, on right, on the podium with Bill Whittington. Rob Hermann

The Whittington Brothers:

If John Paul Sr.’s violent temper made him the most feared of the bad boys, Don and Bill Whittington became the most notorious. The brothers from Ft. Lauderdale burst onto the IMSA scene in 1978, starting with the 12 Hours of Sebring, where Don finished 24th overall in a Porsche 934/5. Racing was in their blood; their father, Don Whittington, Sr., had competed briefly in the USAC Championship Car circuit in the late 1950s.

The younger Whittingtons were soon entering their own 935s in the sprint races and co-driving in the longer events. No one in the paddock seemed to know much about them, yet the pair learned quickly, with Bill finishing second in Camel GT points in 1979 and Don finishing fourth. The following year, they won the prestigious 24 Hours of Le Mans, co-driving with Klaus Ludwig in the first-ever Kremer Porsche 935 K3, which they then purchased and brought to IMSA.

The Whittington’s bright yellow 935s quickly become a force to be reckoned with on the track, but it was their purchase of the Road Atlanta circuit in 1978 that raised the most eyebrows. That, and the fact that they owned several priceless World War II fighter planes including a Grumman Bearcat and two P-51 Mustang warbirds that they raced in the unlimited class at the Reno air races. The 935s were unsponsored, yet no expense was spared in preparing the cars or the planes; money never seemed to be a problem for the duo.

Soon, whispers began to circulate in the paddock about the source of their lavish lifestyle, but IMSA officials certainly didn’t stick their noses into someone else’s business. John Bishop heard the rumors along with everyone else, but he liked Bill and Don. He had a soft spot for airplane guys, especially guys that shared a deep passion for warbirds. The watchwords for the time: “Don’t ask, don’t tell.”

"I guess we should have been gossiping a whole lot more than we were about where these guys got their money,” recalled Bishop later. “At the time, we were incredibly busy just running IMSA. We just didn't give it that big a thought. It wasn't posed as a problem to us by anybody. All we cared about was the quality of the grid and whether the races were going to be run safely and consistently.”

“I knew the Whittington’s well,” recalled Jim Busby. “Bill was actually a pretty nice guy and a heck of a race car driver. We ended up co-driving a few times and won Mid-Ohio together in a 935 one year. And we helped prepare their cars. It was common knowledge in the paddock about their background, but we needed the work and it was none of my business how they paid the bills.”

Following their Le Mans success in 1980, the Whittingtons, now including youngest brother Dale, competed effectively at the sharp end of the Camel GT grid with multiple wins and podiums. In 1984, Bill partnered with Randy Lanier as owners of the Blue Thunder race team that went on to help Lanier win the Camel GT championship that year; Bill finished second in the points. In addition, Bill and Don both started at the Indianapolis 500 five times in the six years between 1980 and 1985, with a best finish of sixth place by Don in 1982. That was the year all three brothers qualified at Indy, an unprecedented and since unequalled feat in the history of the world-famous race.

The good times wouldn’t last. The Whittington empire came crashing down in 1986 when federal authorities indicted Bill and Don on money laundering, tax evasion and drug smuggling charges. Along with Lanier, the Whittingtons were operating a massive marijuana smuggling operation that involved fast boats and multiple airplanes. Some even suggested that the reason they purchased Road Atlanta in the first place was to use the relatively secluded back straight as a landing strip for their illicit activity.

Bill was sentenced to 15 years in federal prison in 1986 when he plead guilty to tax evasion and conspiracy charges. Don was sentenced to 18 months for money laundering in connection with the whole scheme. As part of the plea deal, the brothers had to make a $7 million restitution to the government, which included selling the P-51 Mustangs, the 1979 Le Mans-winning 935, other race cars and team equipment. Don was paroled in 1988 and Bill was released in 1990. They returned to the business of flying, opening a plane leasing company based in Florida.

Investigators determined that Dale Whittington, the youngest of the three brothers, was not involved in the operation and he was never charged with any crime. Dale went on to compete in the IMSA American Le Mans Series in 1999 and 2000 before dying of a drug overdose in 2000.

At Road Atlanta race weekends from 1979 through 1983, the Whittington brothers would often make a grand entrance by shutting down all track activity in the middle of the day so they could buzz the field in their matching P-51 Mustangs and then land on the back stretch. Once on the ground, the fighter planes would taxi up the hill, underneath the bridge leading onto the front straight, down the other side of the hill and into the pit area on the outside of the track. It’s fair to say that these were the most spectacular arrivals in the history of IMSA. Mark Raffauf

Don Whittington poses with John and Peg Bishop in front of one of the Whittington brother's Porsche 935s and a Mustang P-51 at Brainerd. Bishop family