Ted Ornas

The Scout's Driving Force

If this brief biography of Ted Ornas by Jim Allen has you eager to learn more, check out the International Scout Encyclopedia by Jim Allen and John Glancy, the end-all be-all Scout compendium packed with everything you ever wanted to know about IHC's finest truck.

Every great achievement has a driving force, a prime mover. The International Scout was a great achievement and it cannot be denied Theodore “Ted” Ornas was the prime mover of that achievement. That is not to say he was solely responsible, he was always careful to spread the credit, but Ornas was the filter and director of the styling parts and that’s where it started. He did not originate the idea but his persistence at pushing it forward, even as executive interest waned, is the reason the Scout got going at the timely moment it did.

On a professional level, and even beyond International Harvester, there was so much more to Ted Ornas than the Scout. Dick Hatch, a designer that was hired by Ornas in ’67 and eventually ran the department, interviewed Ornas in 2008 and those interviews were the last given before his death in March of 2009 at age 91. A few years previous, Howard Pletcher did a video interview of Ted Ornas and between them, we have a pretty good picture of how Ornas reflected on his career. Both Pletcher and Hatch have been great supporters of this book and graciously allowed us to draw from those interviews. Ornas also wrote a family history and Betsy Blume, Ted’s Granddaughter, has allowed us to draw from that as well. The “life and times” of Ted Ornas is probably worthy of a book of its own but we’ll hit some of the high spots for you.

Theodore Ornas was born July 29, 1917 in Cleveland, Ohio, to Theodore and Mary Ornas. Ornas cited no particular childhood motivation to become an industrial designer, not really even having a particular interest in art. After graduating high school, and a short period working at the Cleveland Woolen Mill, he enrolled in the Cleveland Institute of Art in 1935, where he majored in industrial design. Ted defrayed some of the costs by getting what was called a “working scholarship,” whereby he worked as a school janitor in exchange for half the $300/semester tuition.

Ted struggled through school, the first year especially, because he had virtually no art experience. He did manage to find part time work with a local industrial designer but it was without pay and done to gain experience. In his last year at school, 1939, he was selected for a stylist training program at General Motors, where he worked for $75, then $85 per month. A self-described “know-it-all,” he ignored dire advice and left the GM program to work at George Walker Design, doing a bit of just about everything, including some work on IHC projects, until 1945.

In that fateful, historic year, Ornas left Walker, went to work in New York for Donald Deskey and Associates and worked on everything from architecture to yacht design. When that business got shaky, he left to form his own company with a workmate from Deskey, Dwight LeBarre. The pair moved back to Detroit and set up an office in the Ford building. Styling pickin’s were slim but they survived for a year on the small jobs they could generate. In 1947, they were within a week of shutting down when the universe suddenly smiled on them.

Their venture got a new lease on life when International Harvester called about designing a new line of medium and heavy duty trucks. They were desperate but capable men and succeeded in getting the job. Despite a work schedule that caused health issues, Ornas & LeBarre managed to impress IHC with designs that included full-sized models. Along the way, Ornas & LeBarre also did work for Crosley and Nash as well as the beginnings of an IH project for a low cost “austerity truck.”

In 1951, International started courting Ornas for a position in the company and since his partnership with LeBarre was deteriorating on a personal level, Ted took the job. International wanted an in-house designer at Fort Wayne but in the typical schizophrenic IH way, after the courtship, Ted was all but ignored when he got there. Ornas’ new “styling department” was little more than a hastily converted corner of an auditorium with no windows. Ted’s driving personality, cornerstoned by that youthful “know-it-all” attitude, had been annealed and retempered in the forge called business to be at just the right amount of hardness to move him and his department higher in the corporate food chain. By the time the Scout project began in 1958, Ted had acquired better quarters, staff, and a lot more stature within the company for having made the right calls in a number of critical developments.

Relating to International, Ornas was involved in the design of the L and R-Line trucks, which he did mostly as a contractor. As head of styling, he headed the development of the ’55 S-Line trucks, which improved the aging International Light Line by leaps and bounds. Even more telling were the A-Line upgrades that followed in ’57. Ornas was directly responsible for a couple of light duty milestones, the first three-door SUV, the ’57 A-Line Travelall, and the first four-door SUV, the ’61 C-Line Travelall. The Light Line pickups benefitted from better looks and a more roomy cab on his watch. The legendary Loadstar, which debuted in 1962, was one of his proudest achievements and a medium-duty industry icon.

Ornas shepherded the new Scout II to production in 1971 and the S-Line medium and heavy trucks in ’77, but as International’s financial travails and corporate chaos reached epic proportions in the late ‘70s, he began to think about retirement. It isn’t clear how much the impending sale of the Scout line had to do with it, but Ted Ornas finally “put in his papers” in the fall and retired from International in December of 1980 at age 63.

That retirement did not end his career as an industrial designer. Most notably, he was involved with Leo Windecker, the composite materials pioneer that had helped with the Scout SSV development (see Chapter 6), to develop several aircraft projects. None of those bore much fruit and besides some small things, by the time the ‘80s had progressed far, Ted had enrolled in a local college to take some art classes and was active in the Fort Wayne art scene for many years.

The late ‘80s and the ‘90s is when his pivotal role in the development of the Scout became generally known among a growing crowd of Scout collectors and enthusiasts. That status grew. Ornas admitted to being completely mystified at the phenomenon but always expressed appreciation for the admiration

of his work. On some occasions, owners would seek him out at home and arrive unannounced in a Scout. By all reports, he was gracious and forgiving of the intrusion. He was on hand at various times to dedicate or “consecrate” Scout exhibits, such as the SSV displayed at the Auburn Cord Deusenberg Automobile Museum, or the National Auto & truck Museum right next door to each other in Auburn, Indiana. He also wrote short history pieces for various Scout enthusiast publications as well as always being available for interviews. His donation of certain parts of his archive has also enhanced the research facilities of at least a couple of museums.

Inevitably, time would take it’s toll on the robust Ted Ornas and he would move into an assisted living facility with his beloved wife, Esther, in the mid 2000s. Age would slowly claim him and on March 14, 2009, Theodore Ornas would Scout his way into the next world at age 91. Esther would follow just a few months later on August 6 at the same age.

Granddaughter, Betsy Blume, daughter of Ted’s oldest child, Donna, has become the keeper of the Ornas family IH torch. We have been in frequent communication with her over the course of the book as she opened up what remains of Ted’s personal archive to us. In one note she concluded with something that provides a good ending to this short but sweet missive on Ted Ornas:

“I was just thinking the other day, if my grandfather was still alive, what would be the one thing he might want to say in the book. I don't know if there is a way to add anything of a personal nature to the book from my grandfather’s own words (the Howard Pletcher interview) but if there is room or an appropriate place for it, I had this quote in mind. Howard asked my grandfather this; ‘Any final words for all the IH collectors out there that enjoy your products so much?’ My grandfather answered, ‘Well I want to thank ‘em for keeping them alive in their various clubs. I've seen some of the models that these people have refinished, and they’re works of art, and when I see them I get a little lump in my throat.’ I can only add.....Me too grandpa, me too.”

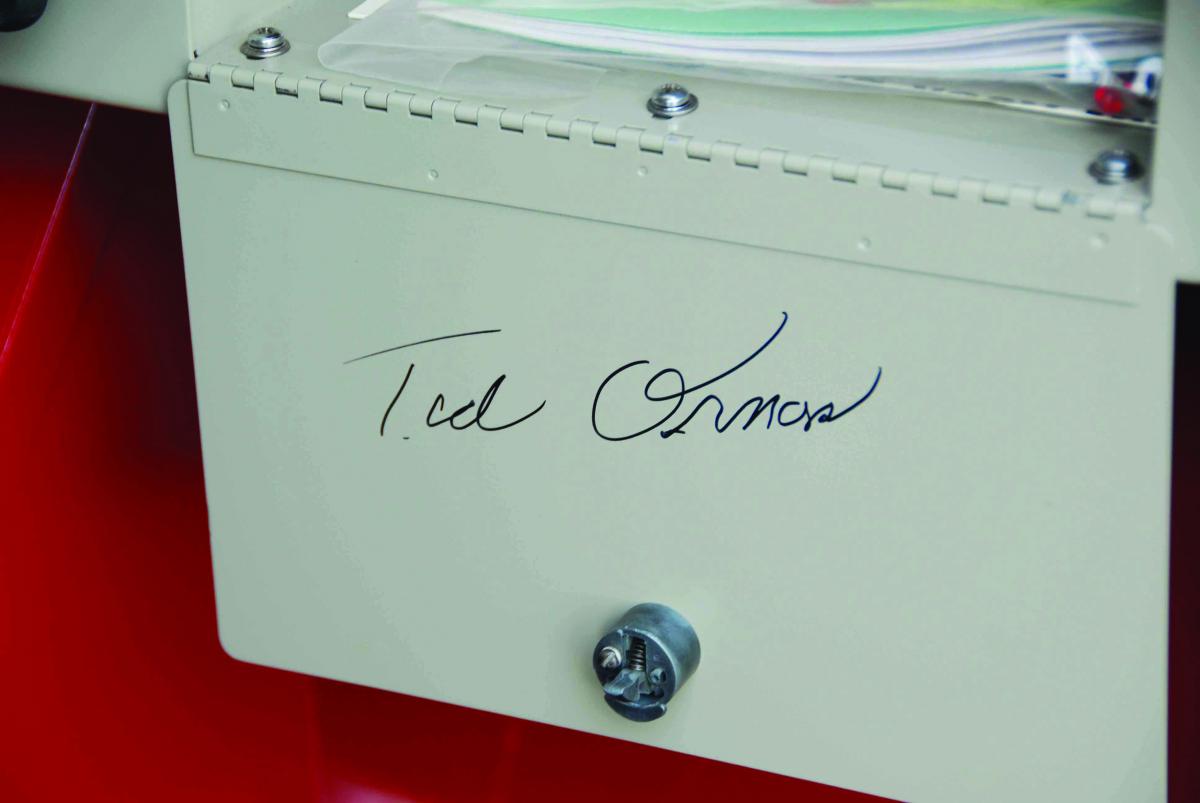

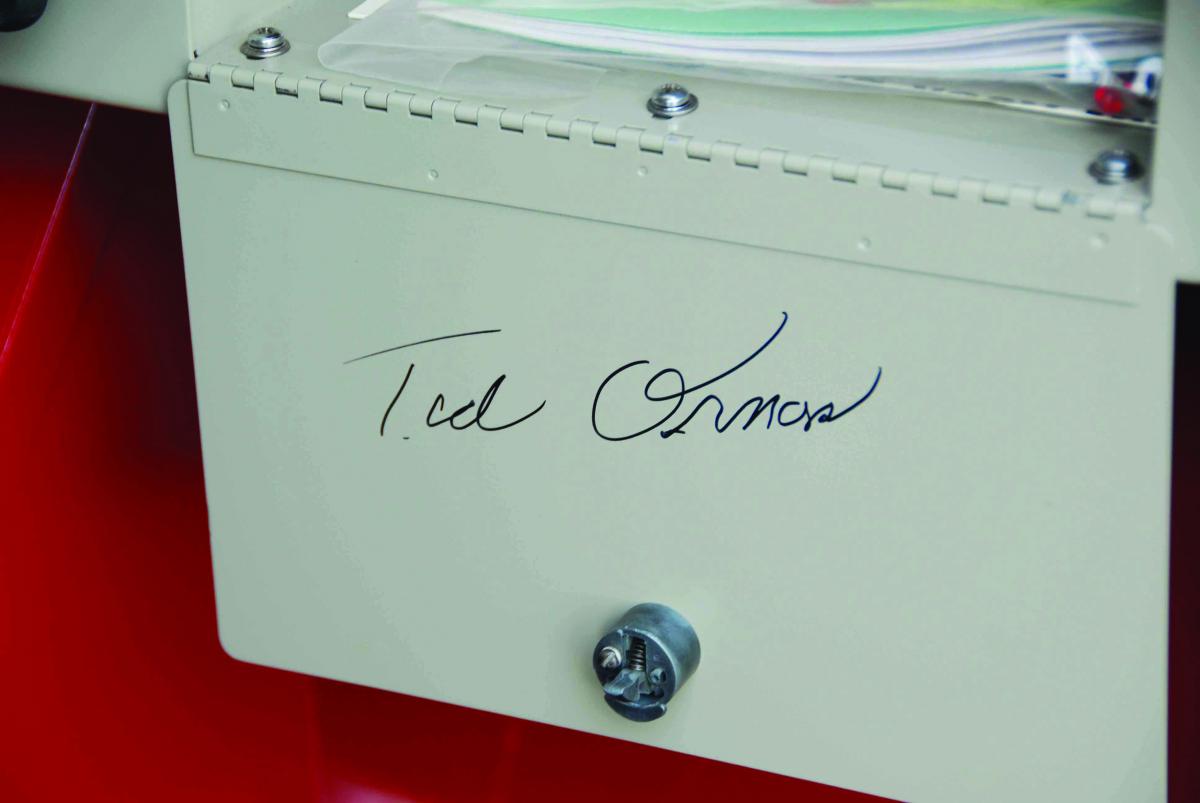

A few lucky people have had Ted Ornas inspect their Scouts. One of the last was Rick Thompson, owner of a red ’62 Scout you will see pictured in the book. That happened in 2006 when Rick paid him a visit. Ted was getting on at the time, but still living at home in Fort Wayne. Rick’s Scout is certainly in the “eye candy” category and Ted so remarked. When asked to sign the inside of the glovebox door, Ted was gracious enough to do it and now Rick’s Scout is among a rare handful so adorned.

A few lucky people have had Ted Ornas inspect their Scouts. One of the last was Rick Thompson, owner of a red ’62 Scout you will see pictured in the book. That happened in 2006 when Rick paid him a visit. Ted was getting on at the time, but still living at home in Fort Wayne. Rick’s Scout is certainly in the “eye candy” category and Ted so remarked. When asked to sign the inside of the glovebox door, Ted was gracious enough to do it and now Rick’s Scout is among a rare handful so adorned.

Ted Ornas was 43 and in his creative prime when this photo was taken in 1969. His “baby,” the Scout had proven to be a hit and the new iteration would do even better. Ornas’ stature and stock price in the International Harvester organization was pretty high at this stage. WHS 110319

Ted Ornas was 43 and in his creative prime when this photo was taken in 1969. His “baby,” the Scout had proven to be a hit and the new iteration would do even better. Ornas’ stature and stock price in the International Harvester organization was pretty high at this stage. WHS 110319

Ted working on one of Leo Windecker’s fiberglass aircraft designs in the early ‘80s. Windecker had debuted a line of fiberglass aircraft in the ‘60s, culminating in the Windecker Eagle. The Eagle AC-7 was FAA certified in 1969, becoming the first composite powered aircraft to do so. Undercapitalized, Windecker’s aircraft venture had failed by the time he worked on the International SSV project but underwent an attempt at revival in the early ‘80s and Ted participated in that attempt.

Ted working on one of Leo Windecker’s fiberglass aircraft designs in the early ‘80s. Windecker had debuted a line of fiberglass aircraft in the ‘60s, culminating in the Windecker Eagle. The Eagle AC-7 was FAA certified in 1969, becoming the first composite powered aircraft to do so. Undercapitalized, Windecker’s aircraft venture had failed by the time he worked on the International SSV project but underwent an attempt at revival in the early ‘80s and Ted participated in that attempt.

Every great achievement has a driving force, a prime mover. The International Scout was a great achievement and it cannot be denied Theodore “Ted” Ornas was the prime mover of that achievement. That is not to say he was solely responsible, he was always careful to spread the credit, but Ornas was the filter and director of the styling parts and that’s where it started. He did not originate the idea but his persistence at pushing it forward, even as executive interest waned, is the reason the Scout got going at the timely moment it did.

On a professional level, and even beyond International Harvester, there was so much more to Ted Ornas than the Scout. Dick Hatch, a designer that was hired by Ornas in ’67 and eventually ran the department, interviewed Ornas in 2008 and those interviews were the last given before his death in March of 2009 at age 91. A few years previous, Howard Pletcher did a video interview of Ted Ornas and between them, we have a pretty good picture of how Ornas reflected on his career. Both Pletcher and Hatch have been great supporters of this book and graciously allowed us to draw from those interviews. Ornas also wrote a family history and Betsy Blume, Ted’s Granddaughter, has allowed us to draw from that as well. The “life and times” of Ted Ornas is probably worthy of a book of its own but we’ll hit some of the high spots for you.

Theodore Ornas was born July 29, 1917 in Cleveland, Ohio, to Theodore and Mary Ornas. Ornas cited no particular childhood motivation to become an industrial designer, not really even having a particular interest in art. After graduating high school, and a short period working at the Cleveland Woolen Mill, he enrolled in the Cleveland Institute of Art in 1935, where he majored in industrial design. Ted defrayed some of the costs by getting what was called a “working scholarship,” whereby he worked as a school janitor in exchange for half the $300/semester tuition.

Ted struggled through school, the first year especially, because he had virtually no art experience. He did manage to find part time work with a local industrial designer but it was without pay and done to gain experience. In his last year at school, 1939, he was selected for a stylist training program at General Motors, where he worked for $75, then $85 per month. A self-described “know-it-all,” he ignored dire advice and left the GM program to work at George Walker Design, doing a bit of just about everything, including some work on IHC projects, until 1945.

In that fateful, historic year, Ornas left Walker, went to work in New York for Donald Deskey and Associates and worked on everything from architecture to yacht design. When that business got shaky, he left to form his own company with a workmate from Deskey, Dwight LeBarre. The pair moved back to Detroit and set up an office in the Ford building. Styling pickin’s were slim but they survived for a year on the small jobs they could generate. In 1947, they were within a week of shutting down when the universe suddenly smiled on them.

Their venture got a new lease on life when International Harvester called about designing a new line of medium and heavy duty trucks. They were desperate but capable men and succeeded in getting the job. Despite a work schedule that caused health issues, Ornas & LeBarre managed to impress IHC with designs that included full-sized models. Along the way, Ornas & LeBarre also did work for Crosley and Nash as well as the beginnings of an IH project for a low cost “austerity truck.”

In 1951, International started courting Ornas for a position in the company and since his partnership with LeBarre was deteriorating on a personal level, Ted took the job. International wanted an in-house designer at Fort Wayne but in the typical schizophrenic IH way, after the courtship, Ted was all but ignored when he got there. Ornas’ new “styling department” was little more than a hastily converted corner of an auditorium with no windows. Ted’s driving personality, cornerstoned by that youthful “know-it-all” attitude, had been annealed and retempered in the forge called business to be at just the right amount of hardness to move him and his department higher in the corporate food chain. By the time the Scout project began in 1958, Ted had acquired better quarters, staff, and a lot more stature within the company for having made the right calls in a number of critical developments.

Relating to International, Ornas was involved in the design of the L and R-Line trucks, which he did mostly as a contractor. As head of styling, he headed the development of the ’55 S-Line trucks, which improved the aging International Light Line by leaps and bounds. Even more telling were the A-Line upgrades that followed in ’57. Ornas was directly responsible for a couple of light duty milestones, the first three-door SUV, the ’57 A-Line Travelall, and the first four-door SUV, the ’61 C-Line Travelall. The Light Line pickups benefitted from better looks and a more roomy cab on his watch. The legendary Loadstar, which debuted in 1962, was one of his proudest achievements and a medium-duty industry icon.

Ornas shepherded the new Scout II to production in 1971 and the S-Line medium and heavy trucks in ’77, but as International’s financial travails and corporate chaos reached epic proportions in the late ‘70s, he began to think about retirement. It isn’t clear how much the impending sale of the Scout line had to do with it, but Ted Ornas finally “put in his papers” in the fall and retired from International in December of 1980 at age 63.

That retirement did not end his career as an industrial designer. Most notably, he was involved with Leo Windecker, the composite materials pioneer that had helped with the Scout SSV development (see Chapter 6), to develop several aircraft projects. None of those bore much fruit and besides some small things, by the time the ‘80s had progressed far, Ted had enrolled in a local college to take some art classes and was active in the Fort Wayne art scene for many years.

The late ‘80s and the ‘90s is when his pivotal role in the development of the Scout became generally known among a growing crowd of Scout collectors and enthusiasts. That status grew. Ornas admitted to being completely mystified at the phenomenon but always expressed appreciation for the admiration

of his work. On some occasions, owners would seek him out at home and arrive unannounced in a Scout. By all reports, he was gracious and forgiving of the intrusion. He was on hand at various times to dedicate or “consecrate” Scout exhibits, such as the SSV displayed at the Auburn Cord Deusenberg Automobile Museum, or the National Auto & truck Museum right next door to each other in Auburn, Indiana. He also wrote short history pieces for various Scout enthusiast publications as well as always being available for interviews. His donation of certain parts of his archive has also enhanced the research facilities of at least a couple of museums.

Inevitably, time would take it’s toll on the robust Ted Ornas and he would move into an assisted living facility with his beloved wife, Esther, in the mid 2000s. Age would slowly claim him and on March 14, 2009, Theodore Ornas would Scout his way into the next world at age 91. Esther would follow just a few months later on August 6 at the same age.

Granddaughter, Betsy Blume, daughter of Ted’s oldest child, Donna, has become the keeper of the Ornas family IH torch. We have been in frequent communication with her over the course of the book as she opened up what remains of Ted’s personal archive to us. In one note she concluded with something that provides a good ending to this short but sweet missive on Ted Ornas:

“I was just thinking the other day, if my grandfather was still alive, what would be the one thing he might want to say in the book. I don't know if there is a way to add anything of a personal nature to the book from my grandfather’s own words (the Howard Pletcher interview) but if there is room or an appropriate place for it, I had this quote in mind. Howard asked my grandfather this; ‘Any final words for all the IH collectors out there that enjoy your products so much?’ My grandfather answered, ‘Well I want to thank ‘em for keeping them alive in their various clubs. I've seen some of the models that these people have refinished, and they’re works of art, and when I see them I get a little lump in my throat.’ I can only add.....Me too grandpa, me too.”

A few lucky people have had Ted Ornas inspect their Scouts. One of the last was Rick Thompson, owner of a red ’62 Scout you will see pictured in the book. That happened in 2006 when Rick paid him a visit. Ted was getting on at the time, but still living at home in Fort Wayne. Rick’s Scout is certainly in the “eye candy” category and Ted so remarked. When asked to sign the inside of the glovebox door, Ted was gracious enough to do it and now Rick’s Scout is among a rare handful so adorned.

A few lucky people have had Ted Ornas inspect their Scouts. One of the last was Rick Thompson, owner of a red ’62 Scout you will see pictured in the book. That happened in 2006 when Rick paid him a visit. Ted was getting on at the time, but still living at home in Fort Wayne. Rick’s Scout is certainly in the “eye candy” category and Ted so remarked. When asked to sign the inside of the glovebox door, Ted was gracious enough to do it and now Rick’s Scout is among a rare handful so adorned.  Ted Ornas was 43 and in his creative prime when this photo was taken in 1969. His “baby,” the Scout had proven to be a hit and the new iteration would do even better. Ornas’ stature and stock price in the International Harvester organization was pretty high at this stage. WHS 110319

Ted Ornas was 43 and in his creative prime when this photo was taken in 1969. His “baby,” the Scout had proven to be a hit and the new iteration would do even better. Ornas’ stature and stock price in the International Harvester organization was pretty high at this stage. WHS 110319 Ted working on one of Leo Windecker’s fiberglass aircraft designs in the early ‘80s. Windecker had debuted a line of fiberglass aircraft in the ‘60s, culminating in the Windecker Eagle. The Eagle AC-7 was FAA certified in 1969, becoming the first composite powered aircraft to do so. Undercapitalized, Windecker’s aircraft venture had failed by the time he worked on the International SSV project but underwent an attempt at revival in the early ‘80s and Ted participated in that attempt.

Ted working on one of Leo Windecker’s fiberglass aircraft designs in the early ‘80s. Windecker had debuted a line of fiberglass aircraft in the ‘60s, culminating in the Windecker Eagle. The Eagle AC-7 was FAA certified in 1969, becoming the first composite powered aircraft to do so. Undercapitalized, Windecker’s aircraft venture had failed by the time he worked on the International SSV project but underwent an attempt at revival in the early ‘80s and Ted participated in that attempt.