The Britten Motorcycle Team Takes on the Land-Speed Record

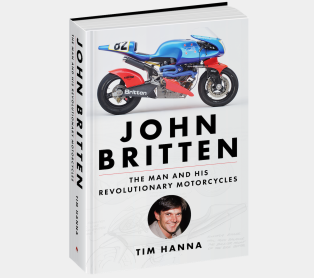

The following is an excerpt from the book John Britten by Tim Hanna,

The book covers how independent John Britten and his revolutionary racing machines beat the factory-built twin-cylinder motorcycles of the time. The legend of the man and machine is one of the most incredible engineering and design feats of the twentieth century.

In this excerpt, the Britten Team takes on their first of several attempts to conquer land-speed records around the world . . .

It was none other than the mercurial Jon White, first encountered during South Island race trips in the 1980s, who was now responsible for one of the most extraordinary episodes in the history of Britten Motorcycles…

It was natural—if ambitious beyond all normal, reasonable expectations—that Jon would use his proven talents and undoubted courage to pursue international motorcycle speed records. It was his destiny. From the beginning Jon had little interest in breaking only national records, although they would have to fall along the way. His goal was to set international records; specifically, he wanted to be the fastest man on two wheels in the world. Having conceived the idea, he threw himself into the project with such ferocious and single-minded determination that he succeeded in attracting a significant level of support.

You have to sacrifice everything if you want to go for world records. Everything! The project cost a total of about NZ$250,000 and I raised the lot. My brother Dennis cut through all the red tape to organize the officialdom, which was just as well as they couldn’t have made it any harder. We were selling electric-blue models of the streamliner with “200 MPH” written on the sides behind the Britten logo to raise funds. I gave some models away while one guy gave me NZ$20,000 for his. We got sponsorship from people like Mobil, and Highway 61 chipped in. (I got a lot of flak for having their name on the streamliner, but they earned it.) An old mate from Auckland called Bill Wallace put about NZ$50,000 in the kitty. Old Bill had been in charge of electroplating at Air New Zealand and when he later set up his own business he did really well. He became like a father to me, full of wisdom and kindness, and he couldn’t do enough to help.

Jon was able to commission Ken McIntosh to build a frame for his cigar-bodied special, which he christened White Lightning, and enlisted the help of well-known yacht designer Digby Taylor to design the shape. Streamliners present a number of unique and complicated design challenges. They must be as slippery as possible and that means they cannot generate downforce to keep them on track, as this only constitutes speed-sapping drag. On the other hand, for obvious reasons, they cannot generate lift. They must be perfectly neutral and must be stable at high speed. The shape that Taylor evolved was a thing of rare and dynamic purpose, a beautifully proportioned torpedo that was extensively refined following comprehensive wind-tunnel testing. As Jon recalled:

We made a model out of welding rods that ended up being the exact structural model for the real thing. Then it was a matter of making triangles with the rod until we had the complete structure. Next, we put a skin on it and tested the model in the wind tunnel at Canterbury University. I was there for about two years off and on making sure we were on track. The professor used to treat me like one of the students, telling me off when I played up or did something wrong. Along the way we had to make various modifications to our initial design, like deleting the hump over the front wheel because it was causing turbulence. We also shortened the body up when we found that left cleaner air behind. We ended up with a really slippery and stable shape.

Streamliners also present a huge challenge when it comes to the construction of the body. Basically, the smallest asymmetricity will cause pressure on one side or the other, which will in turn slowly cause the machine to get sucked off course, or worse, as speeds rise. The body must therefore be perfectly regular and flawless.

The end product, after two years of dedicated graft, was a stunning carbon-fiber and Kevlar sandwich skin that slipped around the McIntosh skeleton, the whole unit fitting Jon White’s narrow frame like a glove…

Jon’s immediate target was the outright New Zealand land-speed record set by Rodger Freeth in the IndyCar, during which attempt, all going well, he would also snare the flying-mile and flying-kilometer records for motorcycles up to 1000cc (then standing at 190.44 mph and 185.74 mph). His final objective in New Zealand was to crack the 200-mph barrier, and then it was off to the salt flats of Utah to go for the big one, the world motorcycle land-speed record. Jon was not alone in seeking to set new speed records in New Zealand. His partner, Alice Walby, was a speed queen in her own right and she intended to set speed records for production motorcycles on her 1200cc Triumph Daytona.

Hans-Gunther von der Marwitz, a German FIM official, was contracted to supervise the event and arrangements were made to close South Eyre Road, site of the BEARS speed trials, which was duly surveyed to ensure that it met gradient requirements and so on. In obtaining FIM cooperation, Jon was greatly assisted by the ever-helpful John Shand, but the costs of bringing Hans-Gunther out were still prodigious…

---

At first light on the morning of Saturday, November 27, 1993, the stunning-looking projectile sat growling on idle at the white start line painted across South Eyre Road. A shimmer of heat haze wavered around the open engine compartment as a thin stream of exhaust smoke mingled with the still, dense morning air. Conditions were judged ideal for the attempt, even if the location left many feeling distinctly apprehensive as they peered into the distance down the narrow, steeply cambered road between the trees and telephone poles that studded its verges. One observer was later quoted in the Australian magazine Performance Cycle saying that “the road looked dangerous, the complete opposite of Wigram. Someone muttered it was like looking down the barrel of a gun, from the wrong end.”

When all was ready, Jon dumped the clutch and accelerated strongly. He quickly lifted the “trainer” wheels and the 260-kilogram streamliner almost immediately started to weave, and then it drifted off the steep road camber to the left, flopping over on its side on the grass verge and sliding to a halt.

“The rough chip surface of the road created this horrible noise inside the shell with the gear down,” Jon recalled, “and with the bodywork acting like a drumskin the deafening din made it almost impossible to function. I lifted the wheels too soon again just to be rid of it and then couldn’t steer the machine.” The damage was not substantial, being largely confined to the tail, and Jon elected to have a second run without it.

I got it up to about 150 mph in the second mile and settled down before starting to feed it some more throttle. It accelerated so smoothly it felt effortless. I don’t know exactly how fast we finally went but I remember that with the power of the Britten engine and with so little air resistance it felt as if it would just keep going faster and faster and faster. But it was bloody hard to see where I was going. I wanted to lift my head to see over the nose at the centerline but couldn’t. Instead, I had to look down the side and gauge my position from the edge of the road. However, I finished the run all right and we turned it round and lined it up for the drive back.

The return run proved a different story. Jon got into third gear and was accelerating hard at about 120 mph when the machine went suddenly out of control.

It fell on its side and slithered along the verge, finally coming to rest after bouncing off a wire fence. Thankfully, Jon emerged again unscathed save a damaged finger on his right hand that would remain “buggered” for the rest of his life. However, he had been extremely lucky, and he would also always carry the memory of a huge old macrocarpa tree tearing toward him as he viewed the world sideways, before it whisked past only inches from his head.